Susan Emanuel on Translating The Belle Époque

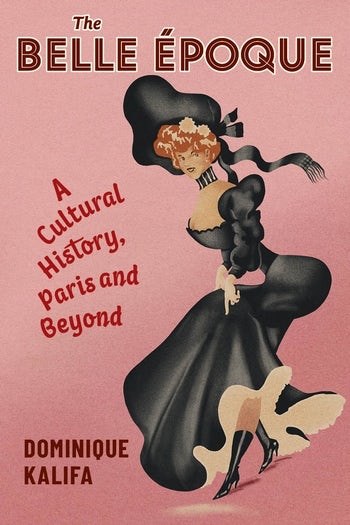

The cover image for The Belle Époque: A Cultural History, Paris and Beyond typifies how most people conceive of the period before 1914, when the First World War broke out. Nobody at the time used the term Belle Epoque, which was retrospectively applied to an age of supposed insouciance before the war, the centerpiece being the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900. There is a detective thread to all of Dominique Kalifa’s cultural history, including his book Les Bas Fonds (translated for CUP as Vice, Crime, and Poverty); on each subject, he traces how social imaginaries evolve over time and space. The French title of the new book is La Véritable histoire de la Belle Époque, harking back to earlier work on pulp fiction.

The perceived origin of this chrononym (a name for an era that gradually prevails in social awareness to define the identity of a period ) was erroneously backdated to a presumed “festival” atmosphere and pre-war artistic ferment, in isolation from political factors like the apogee of the Fourth Republic and economic ones like the technologies of mass culture.

One of the few French historians to use ethnographic sources, Kalifa illustrates the terminological confusion with an anecdote about his students doing a sidewalk opinion sample and finding that some respondents thought “Belle Epoque” meant what we call the Roaring Twenties. Common to all mis-datings is the idea of a paradise perdu.

At first an imaginaire that was totally Parisian, gradually every French resort and region resurrected its own Belle Epoque through old postcards and archive film clips…

So the first problem for me as translator was to adapt this particular imaginaire (his key term) for a non-French readership: not that the French concept is foreign, it has just been (and continues to be) appropriated, in different national ways, to serve contemporary needs, a theme that is developed in each of the three historical sections: 1900, mid-century, and the modern obsession with vintage as antidot to the anxiety of the new fin-de-siecle.

It is a surprise to find that the term was first used in a 1936 operetta (“Ah, la belle époque”). But it only developed into a cultural wave under the Nazi Occupation: theater and radio producers needed inoffensive entertainment for the German troops—in fact the pink poster on the cover is from the 1943 film version. The culture of Montmartre, typified by the Moulin Rouge, was pressed into service for a reassuring view of French life, though some wartime purveyors of variety entertainment later got into trouble for collaboration. Upon Liberation, the concept was appropriated for different purposes, resulting in a parade of period films, songs, and novels mainly foregrounding high society and extolling the avant-garde cultural ferment. But pulling in another direction in the 1950s were realist songs and films about prostitutes and apaches frequenting the cabarets. In fact, the cover of the original French edition of Kalifa’s book is a still from Casque d’Or: Jacques Becker’s 1952 film, that depicts denizens of the underworld, played by Simone Signoret and Serge Reggiani, gazing through a window at the frivolities of the mondains.

At first an imaginaire that was totally Parisian, gradually every French resort and region resurrected its own Belle Epoque through old postcards and archive film clips running at the old speed so everybody seems to move jerkily—cinema itself had been born at the turn of the century. Novelists were writing family sagas that led up to World War I, celebrities were producing memoirs about their youth in the Belle Epoque, and so on. And the idea quickly crossed the Channel: as early as 1934, a “Girl from Maxim’s” joined the war effort (see the Korda film poster).

Therefore the translator must constantly assess which specific manifestations are accessible to a foreign readership.

Exported internationally (the English subtitle of my translation is Paris and Beyond), thanks to glossy films like French Cancan (Renoir, 1955) appealing to worldwide audiences fascinated by the Belle Epoque, the portrait of this era was promoted by vogues in fashion, art (exhibitions of Toulouse-Lautrec et al.), the marketing and branding of nostalgic artifacts, and the continuing prominence for tourists of the Moulin Rouge and its cancan. Eventually it came to New York in the form of the Metropolitan Museum’s Belle Epoque show (1981), whose celebrity gala recreated the experience of dining at Maxim’s.

There is discrepancy between the indigenous nation’s imaginaire and the way that this develops both over time (from 1940s film anthologies like Paris 1900 to modern theme parks) and over space, as other countries hark back to their own golden periods (whose starting points vary, though 1914 is usually the endpoint). Therefore the translator must constantly assess which specific manifestations are accessible to a foreign readership. Do you retain citations from novelists and critics who were prominent in France but whose influence did not extend beyond the Hexagon? Do you include the illuminating lyrics to songs like “Ah, la Belle Époque” that did not circulate abroad either? How does the fin de siècle’s anomie or the Dreyfus affair’s strife or the sinking of the Titanic fit into this tapestry? And how do different cultural histories treat the same concept? Is the British equivalent actually the Gay Nineties and the American one the Gilded Age, as Venita Datta’s brilliant postscript discusses, or are the national contexts too different? In recent historiography, Belle Epoque has become a chapter in European history as a whole.

Dominique’s final book as sole author was about Paris as the Capital of Love…

One of the highlights of Kalifa’s book are the mini-essays placed between the three historical parts: reflections on writing cultural history, on nostalgia, and on our own relation to our forebears as we gaze at men and women in odd outfits looking shyly at a camera in heritage photographs or archival film, especially given our knowledge of the catastrophe that awaits these people, both those who would go off to war and those on the home front. In his epilogue, Kalifa quotes Walter Benjamin about the angel of history looking backward and then adds, “We know how much the past lives on in the present, which in turn determines how it is used, as well as how much it is up to the future to reinvent it. . . . The history of the ‘Belle Époque’ offers a clear demonstration of this: it truly exists only because we have needed it to.”

For this translator, who collaborated with Dominique Kalifa on two books over several years and attended his Tuesday seminars at the nineteenth-century institute at the Sorbonne (alongside scores of graduate students from around the world), this relation to the past became tragic in the fall of 2020 when Kalifa died by his own hand, just before revising the final manuscript. This meant not only that my queries to the author would remain unanswered, that I had to pilot the book through to publication, deciding on illustrations (with the help of his AA Sophie L’Hermitte and editor Jennifer Crewe’s team at CUP), checking notes, and updating a bibliography—all in the absence of a beloved author and collaborator who had an excellent command of English and an amazing breadth of cultural history. The epilogue to this exploration of a period that meant so much to him was quoted at a memorial service: “Our relation with the past means admitting that one always writes inside a tangle of temporalities, in this kaleidoscopic ‘between times’ that is constitutive of History.’

Dominique’s final book as sole author was about Paris as the Capital of Love, which is delightful in its own way (how and where, since Hausmann reconfigured the city, men have tried to chase skirts). I hope this “histoire érotique” will eventually be my final work of translation, as well as cultural history’s homage to Dominique Kalifa. To paraphrase Maurice Chevalier, “God, but [he] seemed happy to be alive.”

Susan Emanuel is a French-to-English translator who for more than forty years has translated books, articles, and blogs in the social sciences, history, and philosophy. She is the translator of Vice, Crime and Poverty, and The Belle Époque: A Cultural History, Paris and Beyond, both by Dominique Kalifa. Her first literary translation, Aline Kiner’s The Night of the Beguines, set in medieval Paris, will be published next year.