How the Harvey Weinstein Verdict Changed the Credibility of Women’s Testimony

By Leigh Gilmore

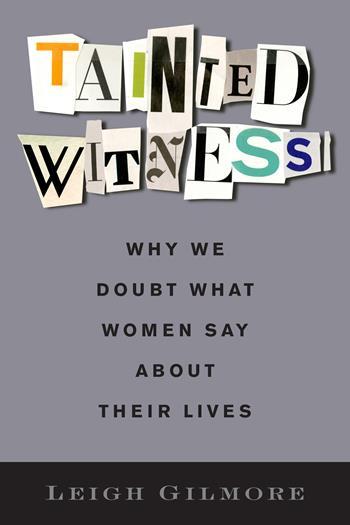

“In this moving and transformative text, Leigh Gilmore explores the different ways that women’s testimonies are made incredible. With patience and care, Gilmore explores how testimonies circulate, how they keep open histories that have yet to be resolved, and how testimonies become tainted because of who as well as what they point to. This insightful book gives testimony a feminist hearing.”

Sara Ahmed, author of Living a Feminist Life and Willful Subjects

Today is International Women’s Day, and as we take the day to commemorate women’s achievement throughout the world and to discuss how to forge a gender-equal society, we invite you to reflect on the Harvey Weinstein verdict and its significant role in empowering women. On February 24, 2020, the jury found Weinstein guilty of rape and sexual abuse, despite the defense lawyer’s attempt to discredit the witness. In this guest post, Leigh Gilmore, author of Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives, describes the influence of #MeToo in feminist thought, and the implications of this verdict for the credibility of women’s testimony in sexual assault cases.

• • • • • •

Harvey Weinstein was convicted of two counts of felony sexual assault in a case many understandably regarded as a verdict on #MeToo. The Weinstein case demonstrates my thesis that although women’s testimony is tainted by scandal and judgment, it continues to move in search of an adequate witness. On February 24, 2020, Weinstein’s accusers found that witness.

Weinstein was able to silence women through the trauma of sexual assault, threats of retaliation, elaborate harassment campaigns, and nondisclosure agreements. He had “catch and kill” arrangements with tabloids to suppress stories that would expose his pattern of sexual assault. The tactics he used to hide it, and that deference, extended to both the Manhattan district attorney’s office and reputable news and media outlets like NBC. Given the decades of unchecked abuse, Weinstein appeared unstoppable precisely because his victims were denied the credibility necessary to stop him. The choral power of #MeToo, however, disrupted two entrenched forms of doubt. The first is the false equivalence of “he said/she said.” Second, the refusal to hear women’s testimony as evidence and to prefer, instead, the right to doubt them through the assertion that “nobody knows what really happened.” Weinstein benefited for years from default cultural narratives of women’s unreliability. Nevertheless, women’s testimony persisted.

“Given the decades of unchecked abuse, Weinstein appeared unstoppable precisely because his victims were denied the credibility necessary to stop him.”

In addition to disrupting he said/she said and exposing that “nobody knows what really happened” is a form of epistemic violence against survivors and their capacity to know and name their experiences, #MeToo demonstrated additional forms of new feminist knowledge that emerged in the Weinstein verdict.

In finding Weinstein guilty on two counts, while acquitting him of the charges of predatory sexual assault that carry a life sentence, the jurors accepted a set of facts that it is difficult to imagine prevailing before #MeToo. They accepted that Miriam Haley and Jessica Mann were assaulted by Weinstein and continued to have contact with him. They believed that previous sexual contact is not equivalent to permanent access. And, they believed that sexual violence erupts in the routine conditions of vulnerability that shape women’s lives.

“The verdict shows that juries can reckon with the traumatic shattering of time that is often exploited to discredit witnesses.”

In Tainted Witness, I argue that women are often found to be unsympathetic because they can never be pure enough to evade harm and their vulnerability is used to discredit them. In an interview on “The Daily,” Weinstein’s lead attorney Donna Rotunno said she had never been sexually assaulted because “I would never put myself in that position.” She blamed women for sexual assault and encouraged others to believe that the right kind of woman, a virtuous woman, is unrapeable. Due to how women are tainted by scandal, judgment, and an irrational bias against their credibility, “not credible” and “unsympathetic” are dangerous labels for women as they seek justice.

The verdict is an important bellwether for women’s testimony. It demonstrates that the default to doubt can be disrupted when survivor testimony is aggregated. The collective quality of #MeToo offsets the individualistic framing of he said/she said. It shifts credibility to women, and prevents it from flowing to Weinstein. And, in contrast to the gaslight-style denial that “nobody knows what really happened,” many, many people often know about sexual violence. The verdict shows that juries can reckon with the traumatic shattering of time that is often exploited to discredit witnesses. Distortions in memory can and do coexist with credible testimony. At least for two women in this particular trial, the mechanisms by which women’s testimony is routinely tainted failed to turn them into unreliable witnesses to their own experience.

Read the introduction to Tainted Witness and an excerpt from chapter 1, “Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Search for an Adequate Witness.“