Q&A: A Conversation About the History of U.S. Property Restriction and Finance After the Civil War

Take a walk today and look around. Observe the people strolling through the parks and neighborhoods. Chances are, they vary in background and cultural heritage, but this was not always the case. To kick off Black History Month, Noni Carter and Kristen Martucci interviewed three authors whose works consider the complicated history of property restriction and finance in the United States after the Civil War. In each book, the authors detail the nuanced “double-edged-ness” of the African American experience under both small-scale and large-scale systematic oppression.

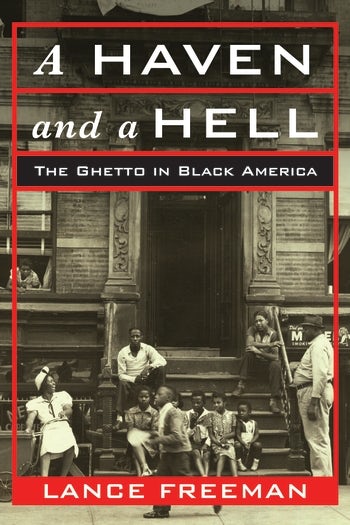

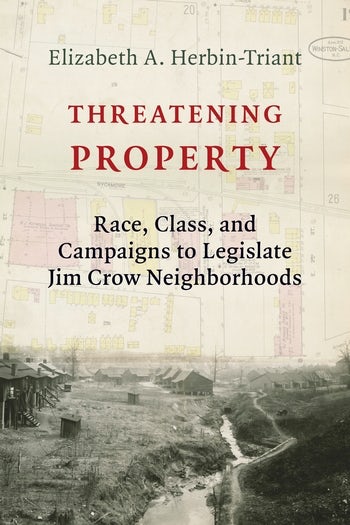

In this Q&A, Elizabeth A. Herbin-Triant, author of Threatening Property: Race, Class, and Campaigns to Legislate Jim Crow Neighborhoods, discusses how the different economic interests of middle-class and elite white southerners gave rise to divergent visions for white supremacy, influencing in particular their perspectives on residential segregation policy. Shennette Garrett-Scott, author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal, illustrates how investment simultaneously created independence for black women and limited their recognition as “economic citizens” in a capitalist society. And Lance Freeman expands on his book, A Haven and a Hell: The Ghetto in Black America, by parsing the layers of duality within the ghetto in reaction to the New Negro Movement and white supremacy.

• • • • • •

Noni Carter and Kristen Martucci: We’d like to begin by thanking all of you for taking the time to discuss your books and research with us. This first question is directed to Lance Freeman. Historians, intellectuals, and everyday Americans have adopted various angles in defining Black America and its sphere of influence. How did you choose the ghetto as both your main focus and the medium through which to explore Black identity, and why is this haven-hell duality important?

Lance Freeman: Ever since childhood I’ve been fascinated by cities: the architecture, the way neighborhoods form, and how their character is maintained. As a Black person interested in cities, the salience of ghettos is inescapable. I was curious why Blacks lived in certain sections of cities and why those neighborhoods were the way they were. I became interested in disciplines that attempt to shape the city—first, architecture and, later, city planning. I looked to city planning as a profession I could pursue to address what ailed many Black neighborhoods—a lack of opportunity, dilapidated housing, etc. But I didn’t think of the ghetto as something that all Blacks wanted to escape. Some did, but some didn’t. These opposing views of living in the ghetto are part of what I attempt to capture in the book by posing it as a duality.

Lance Freeman: Ever since childhood I’ve been fascinated by cities: the architecture, the way neighborhoods form, and how their character is maintained. As a Black person interested in cities, the salience of ghettos is inescapable. I was curious why Blacks lived in certain sections of cities and why those neighborhoods were the way they were. I became interested in disciplines that attempt to shape the city—first, architecture and, later, city planning. I looked to city planning as a profession I could pursue to address what ailed many Black neighborhoods—a lack of opportunity, dilapidated housing, etc. But I didn’t think of the ghetto as something that all Blacks wanted to escape. Some did, but some didn’t. These opposing views of living in the ghetto are part of what I attempt to capture in the book by posing it as a duality.

NC & KM: Throughout the book, the evolution of the ghetto moves parallel to economic, social, and political change. You discuss in chapter 3 how the federal government’s foray into the housing market both enforced segregation and also gave Blacks a platform to direct their own public policies; why do you think this is often overlooked?

LF: I suspect this is because there is a tendency to overlook Black agency when we think about Black American history, particularly when we think about institutions, policies, and practices that severely disadvantaged Blacks. It is also the case that the multifaceted manner in which white supremacy has manifested and served to disadvantage Blacks is often given short shrift in history. So there is an effort to remind Americans of the part that public policy has played in the persistence of racial inequality in the twenty-first century. This effort, however, tends to place Blacks’ actions and perceptions in the background.

NC & KM: Shennette Garrett-Scott, you make the convincing case that Black women, in all of their complex aspirations and ingenious maneuvering, played a unique role in shaping economic institutions of the early twentieth century. Why is telling this story from a uniquely Black feminine perspective important for understanding the current U.S. finance industry?

Shennette Garrett-Scott: The wide gaps in income and wealth between Black women and other racial groups stand today as a bitter monument to Black women’s long history as economic actors who lent, invested, and donated money that built up Black communities. Gender and race together exacerbate those gaps, which persist in spite of positive advances Black women have made in higher education, employment, and business ownership. These factors should spell upward mobility. Credit, however, often remains expensive and elusive. And the blame, or at least the onus, for the state of financial affairs is often shifted onto Black women. For example, Black women are denied conventional mortgage loans at far higher rates than other groups. Lenders insist that underwriting standards do not take race or even gender into consideration. They rely instead on supposedly unbiased factors such as credit scores, debt-to-income ratios, and property values to make credit decisions. That Black women are repeatedly judged unacceptable credit risks reveals the effects of so-called colorblind underwriting as clearly discriminatory. Studies have shown, for example, that credit scores are hardly neutral; they are rooted in racial and sexual discrimination. The reality of continued inequities stand as a sharp rebuke to Black women’s longstanding efforts to secure home ownership, intergenerational wealth, and economic development in Black communities.

Shennette Garrett-Scott: The wide gaps in income and wealth between Black women and other racial groups stand today as a bitter monument to Black women’s long history as economic actors who lent, invested, and donated money that built up Black communities. Gender and race together exacerbate those gaps, which persist in spite of positive advances Black women have made in higher education, employment, and business ownership. These factors should spell upward mobility. Credit, however, often remains expensive and elusive. And the blame, or at least the onus, for the state of financial affairs is often shifted onto Black women. For example, Black women are denied conventional mortgage loans at far higher rates than other groups. Lenders insist that underwriting standards do not take race or even gender into consideration. They rely instead on supposedly unbiased factors such as credit scores, debt-to-income ratios, and property values to make credit decisions. That Black women are repeatedly judged unacceptable credit risks reveals the effects of so-called colorblind underwriting as clearly discriminatory. Studies have shown, for example, that credit scores are hardly neutral; they are rooted in racial and sexual discrimination. The reality of continued inequities stand as a sharp rebuke to Black women’s longstanding efforts to secure home ownership, intergenerational wealth, and economic development in Black communities.

Banking on Freedom highlights aggressive, discriminatory regulation as a serious threat to financial institutions controlled by Black women. Today, the lax enforcement of antidiscrimination statutes gives lenders more ammunition with which to dodge claims that they discriminate. The paucity of Black women in key management and leadership positions in the U.S. finance industry means fewer hands on the levers of power to enact possible reforms. The kinds of practices Black women enacted in earlier eras to address racial and sexual discrimination provide essential lessons for policy makers and lenders. For example, in Banking on Freedom, I highlight ways the St. Luke Bank “embedded racial and gendered economic practices onto standard banking practices to assert a distinct ‘black women’s way’ of banking and managing risk.” The “black woman’s way” in broader terms might include addressing “credit invisible” borrowers: shifting away from an overreliance on credit bureau scores to consider other compelling credit data, such as rent and utility payments, in lending decisions.

NC & KM: In a similar vein, you are careful to make a distinction between “feminists” and those who “would not consider themselves as such.” How did you manage to side-step anachronistic readings (as any historian must do) and locate these women in a feminist history without freely applying this charged term?

SGS: Respecting the sources is one important way to avoid forcing these actors into my own self-serving analytical boxes. Women like the St. Luke founder Mary Prout took great pains to respect ideas about women’s proper place, especially in the church. The kind of work she undertook, however, led her to expand rather than collapse those notions. She pushed the boundaries, to be sure, and some historians do use “protofeminist” as a way to distinguish these women.

The early feminist and suffrage movements also make clear that Black women’s priorities were often considered race issues—not women’s issues. In Banking on Freedom, I left out many details about Maggie Lena Walker’s activism around the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. Previous commitments kept her from attending personally, but Walker worked behind the scenes to help Addie W. Hunton organize a group of women to lobby Alice Paul of the National Women’s Party in early 1919. The women wanted Paul to demand a congressional investigation of the disenfranchisement of Black women in the South. Paul dodged the women, even telling them to meet on a day she would be out of the office. When finally cornered by the group of more than fifty women, Paul refused their requests. She also blocked Black women’s participation in suffrage-related protests and events, going so far as to say that antilynching legislation, an issue of central concern to Black women activists, was “not a woman’s measure.” Most early feminists placed Black women outside of the circle of legitimate feminist concerns. Some did not, such as Jessie Daniel Ames of Texas, but interracial alliances typically proved tricky for Black women to navigate. Acknowledging that Black women negotiated difficult currents not only highlights the limitations of the first- and second-wave feminism but also calls attention to the ways they refined an intersectional critique of the U.S. political economy.

NC & KM: Elizabeth Herbin-Triant, in Threatening Property, class plays an influential role in not only who may acquire and use land but also how white people and African Americans could interact. How does gender further complicate this intersectional approach?

Elizabeth Herbin-Triant: I discuss how elites used rhetoric about gender—about the need to “protect” white women from the advances of Black men—to make the case for taking rights away from Black men. One argument they made was that Black men wanted political power in order to gain access to white women. Middle-class whites, whose thinking was shaped by this rhetoric, also believed that excluding African Americans from white neighborhoods would further “protect” their wives and daughters.

NC & KM: What kind of relationships do each of your histories reveal among property ownership, finance (money), and Black citizenship, particularly during the period following the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment?

EHT: My book considers what property ownership meant to African Americans during a period when they were denied political rights and excluded from public spaces or segregated within those spaces. The homes of African Americans were a place where they could enjoy autonomy and build a sanctuary from the indignities they faced in their workplaces and in public spaces. Some African Americans wished to buy in white neighborhoods because they wished to benefit from the municipal services that their tax dollars paid for—services available only in white neighborhoods—and to move their children away from illicit activity (as went on in “houses of ill repute” frequented by white men), which Booker T. Washington complained was not only allowed in Black neighborhoods but was also located near Black schools and churches. They also wished to get out of the units rented to Black people because these units were kept in poor repair and were rented for more than white people would have paid for similar housing. Because they were disenfranchised and couldn’t change things like how tax dollars were spent through voting, they looked to buying property in neighborhoods that they considered more desirable to better their situation.

SGS: By 1870, both the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Freedman’s Bank, institutions intimately linked in the minds of many freedpeople, had been operating for about five years, and both institutions had reneged on their promises to freedpeople. The former had consistently failed to provide freedpeople with land, and the latter was, by then, essentially controlled by Henry Cooke of the Philadelphia banking firm Jay Cooke and Company. The Cooke firm was instrumental in causing the Panic of 1873 and the eventual demise of the Freedman’s Bank. The institutions made it more difficult for Blacks to achieve their freedom dreams, which included land and property ownership and economic autonomy. For example, in its early years, the bank hesitated to extend Blacks credit. The all-white trustees felt Blacks should consistently save money as a way to develop them as moral citizens. Blacks, however, had other ideas about what their savings accounts meant and how the bank fit into their lives. For example, Black women made small and inconsistent deposits, which reflected the realities of their working lives. They relied on interest to build their accounts. They also put their money into institutions they controlled, like mutual aid societies and church societies. When the bank failed in 1874, depositors and their heirs pressed the federal government to make depositors whole. Their efforts met with disappointment more often than success, but their fight for bank refunds informed other demands for economic justice that underlay Black radicalism far into the twentieth century and even today, as in the reparations movement and struggle to close the wealth gap.

NC & KM: Elizabeth, the story you tell is in part about the economic successes of African Americans in the early twentieth century, as Blacks were purchasing property at higher rates than whites in North Carolina by 1910. How did middle-class and elite whites respond to this success, and what is the connection between Black economic success and a rise in segregationist policy?

EHT: Middle-class whites viewed the economic successes of African Americans as coming at the cost of their own advancement; they viewed economic opportunity as a zero-sum game. And so they responded with a vicious backlash, working to pass laws in a number of southern cities that prohibited African Americans from moving into certain neighborhoods (thus stopping them from buying property that middle-class whites wanted). Elites did not respond in the same way to the expansion of Black property ownership, as Black people were not buying property that elites wanted. Elites didn’t feel threatened by Black economic success, as some African Americans were pulling themselves into the middle class but not into the ranks of the elite.

I argue that residential segregation laws did not go further (they were halted by state courts, in some cases, and by the U.S. Supreme Court case Buchanan v. Warley) because they were not supported by elites, who not only did not feel threatened by Black property ownership but also did not want to risk losing access to their Black workers. For example, the North Carolina State Supreme Court, in ruling against Winston-Salem’s residential segregation ordinance, pointed out that an ordinance like this would work against the state’s interest in “retaining the colored laborers in this State.”

NC & KM: Do the legacies of the history of exclusion continue to play out in our communities today?

EHT: Yes, absolutely—this story resonates today. After the residential segregation laws that middle-class whites tried to put in place were declared unconstitutional, people who wanted residential segregation found other ways of bringing this about, such as restrictive covenants, redlining, urban renewal, and the construction of highways that separate Black from white neighborhoods. If you look at Winston-Salem today, which is one of the places that I focus on in my book, it’s suffering from problems associated with residential segregation. A recent study by a team of economists showed the county that it’s located in, Forsyth, to be the third worst in the nation for upward mobility. Also, East Winston—the Black part of town—is separated from th

e rest of the city by highways, has poor public transportation, and is considered a “food desert,” meaning that there aren’t enough grocery stores. Residents of East Winston are working for change, and there’s support for change from other parts of the city—but it’s a difficult thing to undo the effects of years of residential segregation policy.

NC & KM: You each convincingly analyze specific spaces (the ghetto, Jim Crow neighborhoods) and institutions (finance, real estate) as both contested areas of de jure segregation and discrimination as well as conduits of resistance and experimentation; they are exploitative and violently restricting while they simultaneously encourage creative and subversive activity within the Black community. Shennette, can you talk a bit about the paradoxical nature, this “double-edged-ness” (borrowing your term) of these spaces and institutions?

SGS: The St. Luke Bank made borrowing a respectable option for Black women in part by mirroring the quotidian credit sources they already used, such as pawn shops. Its underwriting practices, like most financial institutions at the time, took character, social standing, and other factors into account as measures of creditworthiness but did not work from a priori assumptions that Black women were inherently unsatisfactory credit risks. At the same time, women’s small incomes made them economically vulnerable. Some found it difficult to repay their loans. In Banking on Freedom, I write about how Black women “maintained the appearance of respectability by not communicating financial hardship. Women felt pressure to not highlight their poverty or economic vulnerability in requesting loans, and they felt similar pressures to not reveal their poverty and economic vulnerability as reasons they could not meet their credit obligations” (143). As a consequence, they repeatedly paid the small fees to extend their notes, which often made the small loans even more expensive and padded the bank’s coffers. And so the double-edged-ness: The bank expanded the market for working women’s credit and made borrowing a legitimate path to upward mobility. At the same time, the emphasis on respectability forced many women deeper into debt and helped the bank’s bottom line.

NC & KM: “Labor” is a slippery term, and it manifests itself in different ways in each of your books. For example, economic freedom allowed Blacks to gain independence while being seen as valued workers, yet they were still not seen as direct competitors, especially to white elites.

EHT: In Threatening Property, I explore how middling and elite whites think about Black labor and how this influences their views on whether Black people should live near white people. Middling whites viewed themselves as competing with African Americans for both property and jobs, and they wanted residential segregation laws to “protect” them from this competition. Elites, meanwhile, considered the labor of African Americans essential in their homes and factories and did not want residential segregation laws to limit their access to these valued workers.

NC & KM: We were curious about the methodological choices that led each of you to the particular geographical regions studied in your books. What encouraged these regional histories? Could these areas of choice serve as case studies, applicable to other places within the United States during the periods you cover?

LF: The methodological approach I employed is quite a bit different from most of my other scholarly research, which tends to be quantitative, with regression models, statistical inference and the like. But one of my earlier quantitative projects on gentrification raised a number of questions that could only be answered by speaking directly to people.

EHT: I focus on North Carolina because it was a state where middling whites had more of a political voice than in other southern states. This allowed them to get residential segregation ordinances enacted in cities but also allowed for the consideration of a constitutional amendment that would have segregated the countryside after the model of South Africa (this was pushed forward by Clarence Poe, editor of The Progressive Farmer). I argue that the same impulses toward segregating African Americans existed in other states but that here they made more progress—thus making North Carolina a good case study for understanding the wishes of middling whites even in places where they didn’t have much of a political voice.

SGS: Doing Black business history is a challenge as the critical sources for such history, such as annual reports, board meeting minutes, and financial statements, often are no longer extant. I counted it as amazing fortune that I had access to the St. Luke Bank records, but it is still a fragmented archive. For example, the cashier’s book of letters had 1,000 leaves, but less than a couple hundred were readable because the print had faded. As the St. Luke Bank was the only bank founded by women, the subject necessitated the focus on Baltimore, Richmond, and Harlem, which were some of the strongholds of the Independent Order of St. Luke. The challenges of local, regional, and federal politics and institutions apply similarly to Black banks in other locales, even those without women on their boards. The political economies and dynamics share similarities but also differences. I, for one, am anxious to see Black finance at the center of more narratives to come.

NC & KM: This has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you for your time and for your thought-provoking answers. Readers who would like to delve deeper into the topics can enter our drawing for a chance to win one of these books.

Noni Carter is a historical and speculative fiction author currently completing a PhD in the department of French and Columbia University.

Kristen Martucci is a B.A. Candidate in East Asian languages and cultures and creative writing at Columbia University.