Practicing Tough Love: An Excerpt from The CEO’s Boss

“The CEO’s Boss is a must-read for anyone who looks to be taking the highest position in a company.”

~ Midwest Book Review

Tuesday you learned about Tesla $40 Million lesson in the need to show “tough love” in the boardroom. Yesterday you read William M. Klepper’s preface to the The CEO’s Boss: Tough Love in the Boardroom, and now know why the second edition is will be vital to your success in the boardroom. Continuing with this week’ theme, today we’re rewarding you with a sneak peek of chapter 2, “Tough Love in the Boardroom.” The following section discusses the boards responsibility to understand the CEO’s behavior style and leadership practices.

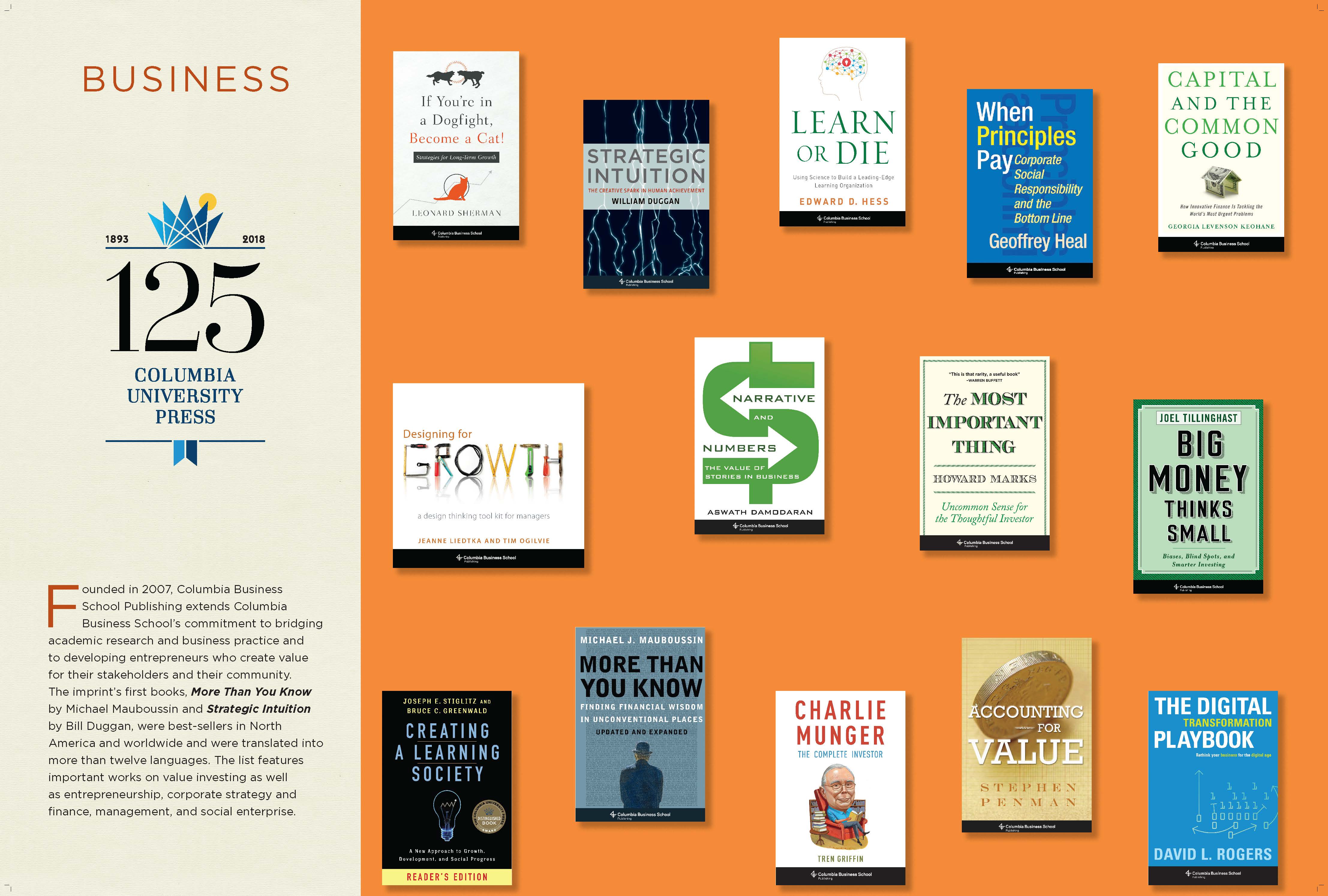

Remember to enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of The CEO’s Boss or anyone title in the Columbia Business School imprint.

• • • • • •

Practicing Tough Love

It is clear, from the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the joint failure of Fuld and the Finance and Risk Committee, that having a statement of intent or a social contract in place is not always enough to ensure a successful partnership. For the board to be able to work effectively with the CEO, it must be able to ask questions, think independently, and show “tough love” when necessary. It is the board’s responsibility to:

- Know the CEO’s behavioral style and leadership practices.

- Know the organization’s needs (strategy, priorities, and gaps).

- Match the organization’s needs with the leadership that is required.

- Look first at the CEO and then the senior team to find the correct match.

- Look elsewhere if the correct match isn’t found.

The CEO’s Behavioral Style and Leadership Practices

Knowing the general behavioral styles of executives can help the board provide tough love to the CEO. The idea of distinct personality types evolved out of the work of Carl Jung. Today one of the most straightforward assessments is based on the behavioral styles research of Merrill and Reed. They define four social styles: driving, expressive, amiable, and analytical.7 In later chapters I discuss how these styles can be modified and expanded into leadership indices that are appropriate for CEO evaluation and I deal more extensively with the assessment of the CEO’s behavioral style and leadership practices. For now, however, let’s consider how different behavioral styles can impact a company.

The CEO changeover at Coke, from Roberto Goizueta to Doug Ivester, is a classic example of the effect different behavioral styles and leadership practices can have on a company. From 1980 until his unexpected death in 1997, Goizueta created more wealth for Coke’s shareholders than any other CEO in history.8 His expressive/innovative behavior was a stark contrast to his COO, Ivester, whose analytical, process-oriented behavior was legendary within the company. In October 1997, although still in shock from losing Goizueta, Warren Buffett and the other directors were convinced that they had the right successor in Ivester, and the board meeting to appoint him lasted only fifteen minutes. Given Ivester’s history with the company and years of working side-by-side with Goizueta, the choice seemed selfevident. As Fortune magazine wrote in 2000:

For two decades Ivester had toiled away patiently inside Coke, the last ten years aiming directly at the top spot and dazzling Goizueta with his hard work and creative execution of company strategy. A onetime accountant and outside auditor, he was carefully groomed by Goizueta and put through all the paces to give him the breadth of experience he would need in marketing, in global affairs, in charm and public speaking. But for all his brilliance—and nobody doubts that Ivester is brilliant—he somehow failed to grasp the vital quality that Goizueta had in abundance: that ethereal thing called leadership. 9

When making its decision, the board did not allow enough time to step back and ask whether and how Ivester’s behavioral style would align with the organization’s needs. The directors apparently assumed that by going with the Number 2 to Goizueta, things would continue as in the past. However, what resulted was a mismatch of a CEO’s style and the needs of an organization. It is reported that Warren Buffett and Herbert Allen, two powerful directors at the time, met with Ivester in a private meeting in Chicago and informed him that they had lost confidence in his leadership after little more than two years on the job. Ivester resigned, and Douglas Daft was appointed to the position soon after.10

When planning succession, the board failed to see that Goizueta was not grooming Ivester as much as he was utilizing his contrasting strengths in his leadership team. When Goizueta and Ivester worked together, Coke functioned at its peak, but a leadership gap was created when one of the players was taken away. If the board had been tougher and more deliberate in its assessment of Ivester’s behavioral style and leadership practices, it might not have had to be so tough on him two years later in assessing his performance as CEO.