Four Steps to Strategic Leadership

“The Wise Advocate is a key book for aspiring leaders aiming to make the best—and hardest—choices. The authors provide a practical guide to decision making through a combination of neuroscience concepts, a process of self-reflection, and consideration of the greatest good for the people one must lead.”

~Marshall Goldsmith, author of Triggers, MOJO, and What Got You Here Won’t Get You There

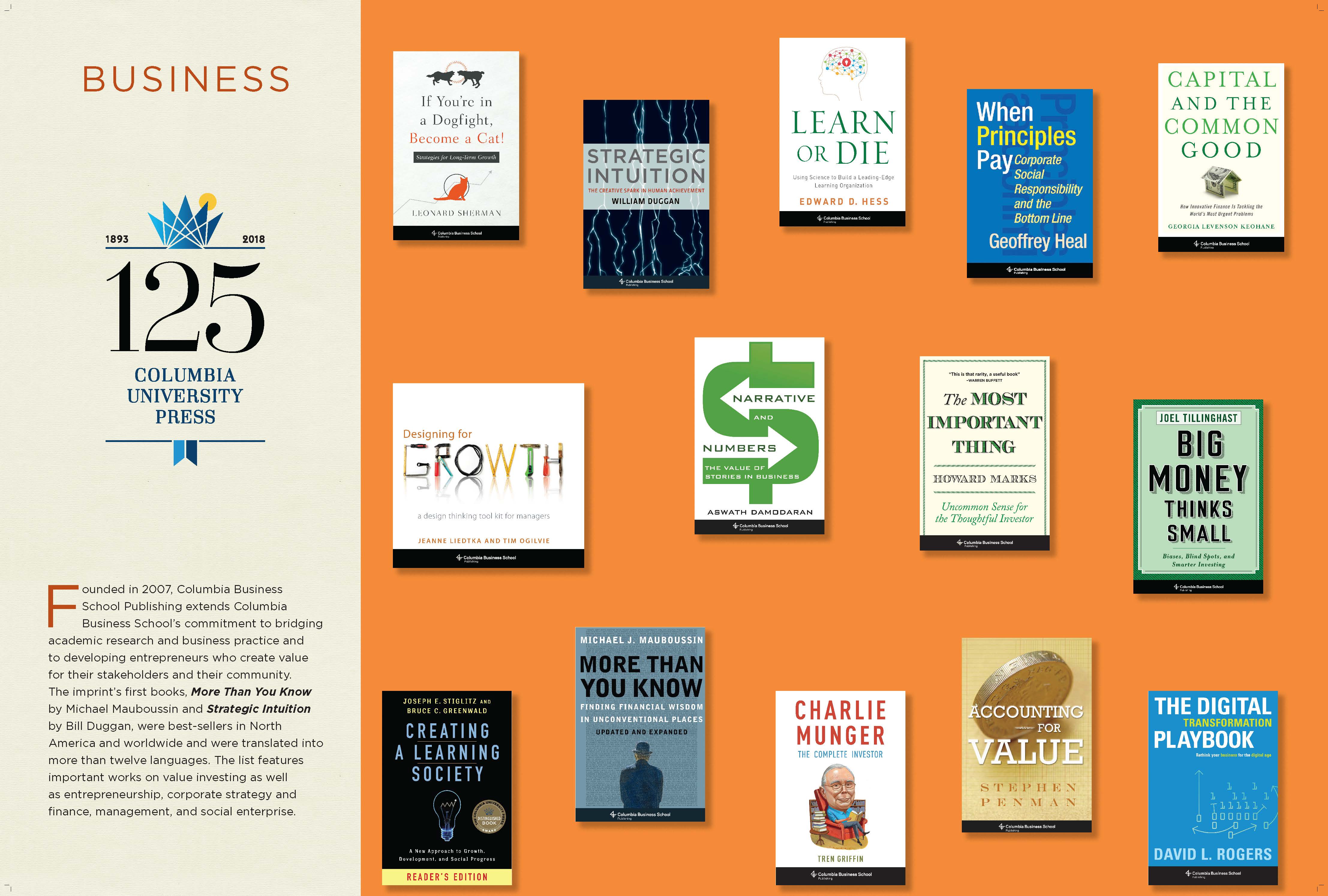

This month, we’re featuring books and authors in our Columbia Business School Publishing (CBS) imprint. Today we have a guest post from Jeffrey Schwartz, Art Kleiner, and Josie Thomson, co-authors of The Wise Advocate: The Inner Voice of Strategic Leadership. In this piece, they discuss Mark Bertolini’s leadership at Aetna in 2015, when he raised the minimum wage in the company to $16 per hour. Why did he make this decision, and how did the process of coming to that decision make him a “wise advocate?” Read on to find out.

Enter to win a copy of The Wise Advocate or any one title in the CBS imprint.

• • • • • •

Each of us makes thousands of choices every day about what path to follow. We decide whether to look out for our immediate interests or for some more distant goal. We don’t always consider these moves consciously, but in all cases there is a choice involved: about whether to pursue the expedient path, solving a problem or giving someone what they want; or whether to do something with more fundamental value. Day by day, over time, the way you navigate these moments creates a capacity, a kind of way of placing your attention, that is often known as leadership. This is a kind of leadership that enables people to face tough challenges, on behalf of themselves and their organizations, and come out with integrity and wholeness. It’s not easy to describe, but you know it when you see it. And in public life, in a world where narcissism is often rewarded, this type of leadership is visible all too rarely.

One place it was visible, in early 2015, was in a U.S. healthcare insurance company called Aetna – the third largest in the country. The chief executive, Mark Bertolini, gave a speech at a call center in Jacksonville, Florida on January 12, announcing that he was raising Aetna’s minimum wage to $16 per hour. For the 5,700 employees who stood to benefit, this meant an average pay increase of 11 percent; some saw an increase of 33 percent. It was arguably the most visible wage hike by a chief executive since 1914, when Henry Ford doubled his assembly line workers’ pay to $5 a day. It was also a harbinger of broader corporate change: WalMart, McDonald’s, and other employers have all announced similar wage hikes since. And to those following issues like income inequality, this was a welcome move that seemed to come from out of nowhere.

“This is a kind of leadership that enables people to face tough challenges, on behalf of themselves and their organizations, and come out with integrity and wholeness. It’s not easy to describe, but you know it when you see it.”

But it didn’t. Bertolini and his organization had been preparing for this move for almost a year. He is since better-known for codesigning Aetna’s pending merger with CVS, but at the time, he was known for an interest in mindfulness and medication, which started after a near-fatal ski accident in 2004. When he took the job as CEO in 2010, just after the passage of the Affordable Health Care Act (otherwise known as ObamaCare), he said he had three objectives: “To [turn Aetna into] a consumer company… to make healthcare reform actually work… and to reestablish the credibility of corporate leadership in the eyes of the American public” – not just for Aetna, but for business in general.

Bertolini, who disliked the inefficiencies of email, began following comments by Aetna employees on an internal company social media network called Aetna Connect. There, and on site visits, he kept seeing comments about employees saying, “I can’t afford my benefits. My healthcare coverage is too expensive.” He and his HR teams looked at a number of options for making life better for low-paid employees. Then he finally said, “How about we just pay them more?” That was the beginning, not the end, of a conversation. First, he asked other senior officials if they thought the organization was ready. He challenged HR to look beyond the immediate costs of such a move, about $10.5 million, to the deeper costs; at the time, employee turnover cost the company $120 million per year. “By that measure,” he recalled later, “$10.5 million looked like a low-risk investment.”

Nor was raising wages enough. They had to adjust medical benefits, which were taking a major toll on employees through cost sharing. In the end, 5,700 employees got wage increases to $16 per hour, and up to 45% increases in total personal disposable income.

“Bertolini focused on the lowest-wage earners in part because they were also the public face of the company; many of them worked in call centers. He was driven by a strong sense of propriety: it wasn’t right to have people in such an indefensible position, and it would hold back Aetna’s efforts to focus on consumers.”

The intensity of thinking that went into this was notable. Bertolini focused on the lowest-wage earners in part because they were also the public face of the company; many of them worked in call centers. He was driven by a strong sense of propriety: it wasn’t right to have people in such an indefensible position, and it would hold back Aetna’s efforts to focus on consumers. But he wasn’t trying to please people. Indeed, employees at the next higher salary level asked, “Where’s my raise?” and Bertolini told them he was disappointed in them. When he finally made the announcement, he recalled, “I had known people would be happy, but I wasn’t ready for the raw emotion. There were people crying. People saying, ‘Praise the Lord. My prayers have been answered.’ The frontline managers were thrilled.”

“There is also reason to believe that those who invoke this mental circuit take on a similar role in their organizations: they become wise advocates to the world around them. This broadens and deepens their influence.”

This type of leadership is not easy to put into words. But you know it when you see it. It turns out that this is not just a subjective perception. A growing body of experimental and observational evidence exists, from neuroscience, social psychology, and organizational dynamics, and the interpretation of that evidence is converging on a conclusion. There is a mental circuit, an inner evocation of the ‘high ground,’ akin to a wise advocate within your mind. It has been consistently observed to invoke particular parts of the brain, in ways that relate to broader perspective and long-range success. There is also reason to believe that those who invoke this mental circuit take on a similar role in their organizations: they become wise advocates to the world around them. This broadens and deepens their influence.

Our book, The Wise Advocate, describes the cycle of applied mindfulness that helps you get there. In this cycle, you habitually become more aware of the thoughts in your mind and in others’ minds; you systematically change the way you respond to them; and you project that same type of focused attention on the systems and organizations around you.

It involves four stages of activity, in which you develop your capabilities as a leader:

- Relabeling: Consciously recognizing deceptive messages (at the individual and collective levels) as thoughts that can be changed, and awakening your awareness of their effect on you.

- Reframing: Replacing or recasting deceptive messages in more constructive ways, and aligning your thinking and behavior (and your organization’s) to these reframed perceptions.

- Refocusing: Regularly practicing these new forms of thinking with attention and commitment, until they become habitual, part of the “second nature” of your daily life and that of your organization.

- Revaluing: Becoming more aware of your influence as a leader, and putting it to better use.

To those unfamiliar with this form of leadership, it may seem “soft” or “unsubstantial” to influence the world around you by changing the way you focus your attention. But the focus of your mind is the most practical tool we have, because it deeply affects the more material-seeming structures around it, from the biology of the brain to the systems and technologies of a vast company. At an individual level, the practice of wise leadership engages you in a lifelong process of discovering your true self. At an organizational level, the practice of wise leadership engages you in manifesting that true self to affect the world at large.

For more about wise advocacy and strategic leadership visit www.wiseadvoc8.com.