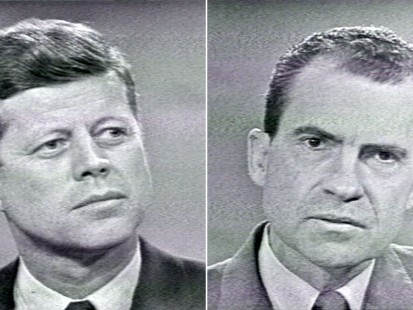

Alan Schroeder on the First Televised Presidential Debate

“That son of a bitch just cost us the election.”—Henry Cabot Lodge, the Republican vice-presidential candidate after the Nixon-Kennedy presidential debate

On the occasion of tonight’s presidential debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, we thought it might be worthwhile to look back at the first televised debate via Alan Schroeder’s Presidential Debates: Fifty Years of High-Risk TV. (For Alan Schroeder’s take on the continuing relevance of presidential debates read his piece in the New York Times, Not Perfect, but They Serve a Purpose or watch him on Current TV)

In his introduction Schroeder recounts Nixon’s now famous (or infamous, depending on your political persuasion) pallid appearance. Perhaps less well-known is the bad advice Nixon received from none other than his running mate Henry Cabot Lodge:

Beyond production considerations, an eleventh-hour phone call from running mate Henry Cabot Lodge apparently helped steer Nixon onto the wrong tactical course. Lodge, who had debated Kennedy in their senatorial race in 1952, advised Nixon to take the high road and “erase the assassin image” that had dogged him throughout his political career. And so it was that Richard Nixon adopted a posture of conciliation, even deference, toward his fellow debater. “The things that Senator Kennedy has said many of us can agree with,” Nixon declared in his opening statement. “I can subscribe completely to the spirit that Senator Kennedy has expressed tonight.” At one point, the Republican nominee chose to forgo a response altogether, passing up the opportunity to rebut his opponent’s remarks.

“Thank you, gentlemen. This hour has gone by all too quickly.” With this coda from Howard K. Smith, the historic encounter drew to a close. In Texas, Henry Cabot Lodge, the running mate who had counseled gentility in his predebate phone call to Nixon, was heard to say, “That son of a bitch just cost us the election.”

Before leaving the studio, Kennedy and Nixon posed for a final round of photographs, making small talk about travel schedules and weather as the shutters clicked away. Afterward, JFK told an aide that whenever a photographer prepared to snap, Nixon “would put a stern expression on his face and start jabbing his finger into my chest, so he would look as if he was laying down the law to me about foreign policy or communism. Nice fellow.”

Outside the TV station, a crowd of twenty-five hundred political enthusiasts had gathered in the street. Asked by a reporter to estimate the ratio of Democrats to Republicans, a Chicago police officer quipped, “I’d say it’s about twenty-five hundred to zero.” As Nixon slipped out the back, Kennedy triumphantly emerged at the main entrance of the building to greet his supporters. “When it was all over,” Don Hewitt said, “a man walked out of this studio president of the United States. He didn’t have to wait till election day.”

In what history records as the first example of postdebate spin, Jacqueline Kennedy turned to her guests at program’s end and exclaimed, “I think my husband was brilliant.”…

Richard Nixon’s first indication that the debate had not gone his way came from longtime secretary Rose Mary Woods, a woman he counted among his most honest critics. Shortly after the broadcast, Woods got a call from her parents in Ohio, who asked if the vice president was feeling well. When the debate aired in California, Nixon’s own mother phoned with the same question. And so the reaction went. “I recognized the basic mistake I had made,” Nixon would write in Six Crises. “I had concentrated too much on substance and not enough on appearance. I should have remembered that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words.’ ”

Indeed. In the days that followed, the thousands of words printed about the first Kennedy-Nixon debate would be no match for the pictures that had seared themselves into the nation’s consciousness. Pat Nixon, flying to her husband’s side the next day, gamely told a reporter, “He looked wonderful on my TV set.” Nixon himself assured interviewers that despite a weight loss, he felt fine. Press secretary Herbert G. Klein lamented that “the fault obviously was television,” while other Republicans voiced public displeasure with their candidate’s kid-gloves approach to his opponent.

JFK, on the other hand, reaped an immediate windfall. Theodore White described the change in the crowds that turned out for Kennedy the next day in northern Ohio: “Overnight, they seethed with enthusiasm and multiplied in numbers, as if the sight of him, in their homes on the video box, had given him a ‘star quality’ reserved only for television and movie idols.” Time magazine wrote that before the debate, reporters had amused themselves by counting “jumpers” in the crowds—women who hopped up and down to get a better look at Kennedy. “Now they noted ‘double jumpers’ (jumpers with babies in their arms). By week’s end they even spotted a few ‘leapers’ who reached prodigious heights.”

Although the mythology surrounding the first Kennedy-Nixon broadcast would greatly amplify in the years to follow, the moral of the story has never varied: presidential debates are best apprehended as television shows, governed not by the rules of rhetoric or politics but by the demands of their host medium. The values of debates are the values of television: celebrity, visuals, conflict, and hype. On every level, Kennedy and his team perceived this, while Nixon and his did not.

After Chicago, campaigns would have no choice but to school themselves in the subtleties of the small screen, and eagerly have they taken to the task. “It didn’t matter whether the televised debate had been decisive in Kennedy’s victory,” wrote social critic Todd Gitlin. “What mattered was that the management of television was one factor that candidates believed they could control. The time of the professional media consultant had arrived.”

Today, with the merger of politics and television complete, presidential debates operate as coproductions of the campaigns. Candidates and their handlers dominate every step of the process, from make-or-break issues like participation, schedule, and format, to such arcana as podium placement, camera angles, and which star gets which dressing room. Nothing is unnegotiated, nothing left to chance.

Still, when the red light blinks on to signal the start of the program, the steamroller nature of live TV supersedes the campaigns’ stewardship. Spontaneity is the overriding determinant of presidential debates, and a major reason, perhaps the major reason, that audiences continue to watch in such staggering numbers. “Modern debates are the political version of the Indianapolis Speedway,” according to political scientist Nelson Polsby. “What we’re all there for—the journalist, the political pundits, the public—is to see somebody crack up in flames.”…

1 Response