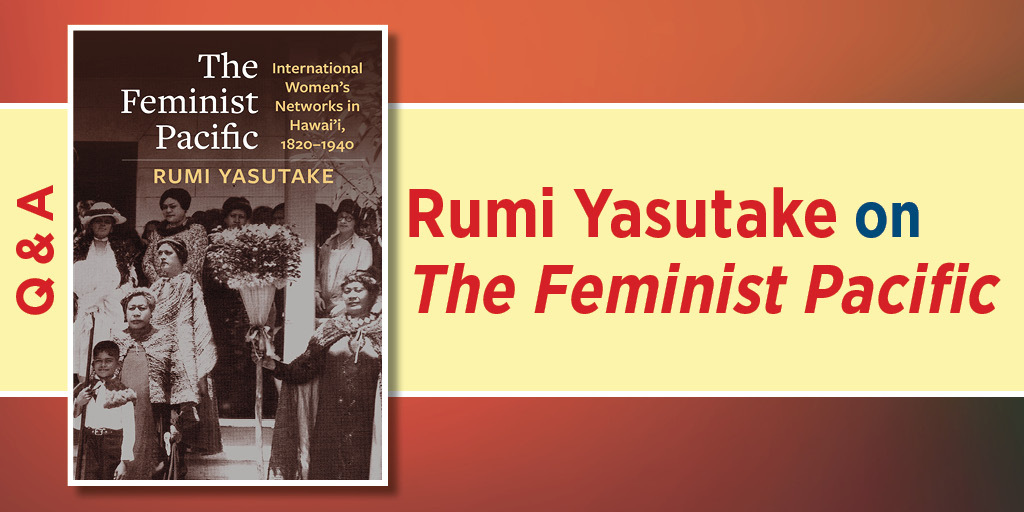

Rumi Yasutake on The Feminist Pacific

Rumi Yasutake’s book, The Feminist Pacific: International Women’s Networks in Hawai’i, 1820–1940, conceptualizes the emergence of pan-Pacific feminism in the process of interacting historical forces and women’s activism in Hawai‘i from 1820 through the 1930s. When a mounting tide of Enlightenment ideas on religious, political, and economic liberalism reached port cities in the North American continent, Protestant missionary women from New England carried them to and across the Pacific, setting a stage for settler colonialism and imperialism. Ensuing massive movements of goods, peoples, and ideas rattled the premodern social orders and feudalistic human relationships. Subsequent social and demographic changes caused social divides and conflicts. The Feminist Pacific traces how small but diverse groups of women interacted, networked, and negotiated for mutual understanding in the wake of the pioneer missionary women. It examines how they facilitated, resisted, and mediated the compelling historical forces in Hawai‘i, where vibrant missionary, suffrage, maternalist, and peace movements emerged. Hawai‘i became the Pacific crossroads of women’s movements to generate pan-Pacific feminism, which attempted to be a force for racial and international harmony and a new world order for permanent peace.

Q: What prompted you to write this book, and what did you do?

Rumi Yasutake: Growing up in Japan, I learned that women missionaries promoted women’s education and helped raise women’s status in the home and wider society. Yet, when I studied history in grad schools in the United States, I was awakened—but also perplexed—by critical assessments of their white, middle-class centricity, of their cultural conservatism, and of their collaboration with white settler colonialism and imperialism. This book began as an exploration of this contradiction. I became interested in the Pan-Pacific Women’s Association (PPWA), the first women’s organization with a Pacific focus, which was organized in the wake of Anglo-Saxon Protestant missionary women. Formed in Honolulu in 1930, the PPWA elected an Asian woman as one of its first vice presidents in 1930 and as its second president in 1934. Its birthplace, Hawai‘i’s port city, served as an American missionary outpost in the early nineteenth century and a thriving hub of trans-Pacific oceanic transportation, linking its Asian settlers’ homelands in the early twentieth century. Honolulu became a gateway for prevailing liberal ideas, capitalist industrialism, and consumer culture to the Pacific, and it was the entry point of Asian immigrants drawn to Hawai‘i’s thriving sugar plantations. Women’s interactions and networking, multidimensional and multilayered, became a part of the trans-Pacific web of a globalizing capitalist system, settler colonialism, and imperialism.

Q: How is this book different from the other work on women’s internationalism?

Yasutake: First, The Feminist Pacific brings Native Hawaiian and Asian settler women into analysis of pan-Pacific feminism and internationalism by examining over a century of women’s movements in Hawai‘i. While this book greatly owes itself to numerous works on the rise of Euro-American women’s internationalism, especially the ones that diverted their Atlantic centricity to the Pacific, I found that their international focus obscured the significant roles played by women in Hawai‘i.

Second, this book presents an overview of the emergence of trans-Pacific women’s networks and feminist identity as a part of globalization—a recurring phenomenon of people’s movements, settlements, interactions, and networking since the prehistoric era. With this approach, The Feminist Pacific avoids judgmental analysis of women activists. It poses a fundamental question: how did women of diverse racial, class, and geopolitical backgrounds navigate the compelling historical forces of the modern era—the prevailing Enlightenment emphasis on the human agency to challenge religious and political absolutism and the globalizing appeal of freedom, democracy, entrepreneurship, and capitalist-industrialism, which led to new competitions, inequalities, and injustices by the end of the nineteenth century. This book encourages exploring the intricate and illusive relationships among people who strove to mediate the geographically uneven but imperative historical forces of the time. It highlights the complexity and transformation of their movements and their profound effects on society.

Q: Tell me about the cover of the book? What’s the story behind the picture?

Yasutake: It showcases the racial and cultural hybridization of women’s leadership through their experiences of multinational settler colonialisms that generated Hawai‘i-led women’s internationalism. The picture captures a scene at the June 1928 ceremony dedicating the renovation-in-progress of the Hulihe‘e Palace at Kailua-Kona on the Big Island. The original palace, a symbol of Hawaiian nobility and sovereignty, was completed in 1838. It used native labor and local materials but adopted a plain, New England architectural style. The Western-style building asserted the “civilized” status of the Hawaiian kingdom in an attempt to fend off European imperialist powers. American missionaries, who began arriving in 1820, assisted the Hawaiian royalty in this effort for survival and facilitated the kingdom’s integration into the globalizing capitalist system. Consequently, Hawai‘i experienced a thriving sugar industry and an influx of settler labor; this led to a republic displacing the kingdom and, later, the U.S. annexation of Hawai‘i. With the end of the Hawaiian monarchy, the Hulihe‘e Palace was neglected until the Daughters of Hawai‘i, a local organization of native and settler women of privileged families, intervened to reverse its physical disrepair through renovation.

The dedication ceremony took place two months before the first Pan-Pacific Women’s Conference in Honolulu. It was not just an appropriation of Hawaiian culture but also a powerful testament to the open-mindedness of Hawaiian traditions and their cultural authority. The woman wearing a hat who stands next to the Kāhili (the token of the divine power of Hawaiian chiefs and nobles) is Julie Judd Swanzy, the honorary chairperson of the upcoming conference and the subsequent PPWA. She was a third-generation descendant of American missionaries, was fluent in the Hawaiian language, and was well-versed in the islands’ traditions. I interpret the scene as a Native Hawaiian endorsement of Swanzy’s leadership in generating pan-Pacific women internationalism, a potential means to sustain the status quo of Hawaiian unity and autonomy at a critical moment of volatile racial, ethnic, and national relations in Hawai‘i, the United States, and the Pacific.

Q: Can you tell me about what you found that you wouldn’t have imagined at the outset?

Yasutake: I was surprised to find the extent of Native Hawaiian and Asian agencies in the course of Hawai‘i’s nonviolent struggles with multinational colonialism and imperialism and in the emergence of pan-Pacific feminist internationalism. No group was monolithic; their causes were varied, and their movements had multidimensional implications. Under the pressure of early nineteenth-century globalization, the Hawaiian tradition of female chiefs’ political leadership yielded to New England’s middle-class norm of “true womanhood.” Native Hawaiian women’s leadership quickly revived, though, in the new electoral system imposed by U.S. imperialism. In the culturally and racially open milieu of the islands, Hawaiian women’s political leadership merged with activist American churchwomen’s “separate sphere” strategy and successfully formed a voting alliance to influence and participate in politics under white male oligarchy. The alliance endeavored to recover women’s rights lost in the U.S. system and maintain unity among the multinational population.

During World War I, Native Hawaiian and missionary-descendant women’s leadership had elite bilingual women represent people of warring states and ethnically divided communities in order to carry out war-support work throughout the islands and to prove their patriotism. Nonetheless, when these elite progressive internationalists of diverse backgrounds came together to press for the Americanization of the islands’ children, Asian settler parents (most conspicuously Japanese, who composed the backbone of Hawai‘i’s plantation workforce) vehemently resisted. The strong opposition of Asian parents to Anglophone cultural hegemony over polyglot Hawai‘i pressed women leaders to seek cooperation with their homelands’ elite internationalists. The emerging pan-Pacific women’s internationalism thus had an aspect of transnationalizing women’s settler colonialism.

At the same time, it became evident that only small groups of progressive bilingual elites assumed overlapping leadership in local affiliates of Anglo-Saxon–origin women’s movements and formed a finite but tightly-knit network for pan-Pacific internationalism. While American national and international leaders competed and conflicted with one another, their movements and causes trickled down to Hawai‘i and other Pacific countries, providing new ways to mediate rapid social changes and advance women’s status. Having inherited evangelical impulses from their ancestor activists, American leaders eagerly introduced and transferred knowledge, expertise, and leadership to bilingual elite women in Hawai‘i to narrow the gap between those who benefited from and those marginalized and exploited by the globalization force. Women sought collective power to insert themselves into the male-dominated international public arena to seek social justice, protect women’s lives, and improve women’s status.

Q: What are The Feminist Pacific’s implications?

Yasutake: Interracial and international women’s networking and dialogues to form pan-Pacific feminism encouraged racial and national harmony. Nonetheless, the expanding missionary-pioneered women’s network, much like its male counterpart, failed to mediate the social changes and divides in China, Japan, and the United States. This had effects on the Chinese Civil War, Japan’s military aggression in China, white racism and exclusionism, and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. In the era of ever-changing globalization, feminist internationalism endeavors to correct past and present injustices, but its slow but hard-fought progress still invites recurring social divides, animosity, and conflicts. It might be impossible to share a common knowledge of past experiences. Still, efforts to understand human actions in their sociohistorical contexts should help develop sympathy to narrow the divides. The Feminist Pacific anticipates further studies to fill in any gaps and work toward a comprehensive picture of the past for a better future.

Categories:American HistoryAsian and Pacific American Heritage MonthAuthor InterviewFeminist TheoryGender StudiesHistoryThemed MonthWomen's History MonthWomen's Studies

Tags:AAPIAsian and Pacific American Heritage Month 2024feminismHawai'iHawaiian HistoryMissionary ImpactPacific HistoryRumi YasutakeThe Feminist PacificWomen In HistoryWomen's History Month 2025Women's Movements

Related Posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

African American / Black Studies / American History / Asian Studies / Business / Economics / Feminist Theory / Fernwood Publishing / Gender Studies / History / Literary Studies / Reading List / Women in Business / Women's History Month / Women's Studies

African American / Black Studies / American History / Asian Studies / Business / Economics / Feminist Theory / Fernwood Publishing / Gender Studies / History / Literary Studies / Reading List / Women in Business / Women's History Month / Women's StudiesSeven Must-Read Books for Women’s History Month 2025