The History of U.S. Capitalism

Yesterday’s New York Times article In History Departments, It’s Up With Capitalism by Jennifer Schuessler explores “the specter of capitalism” in history departments.

As Schuessler explains:

After decades of “history from below,” focusing on women, minorities and other marginalized people seizing their destiny, a new generation of scholars is increasingly turning to what, strangely, risked becoming the most marginalized group of all: the bosses, bankers and brokers who run the economy.

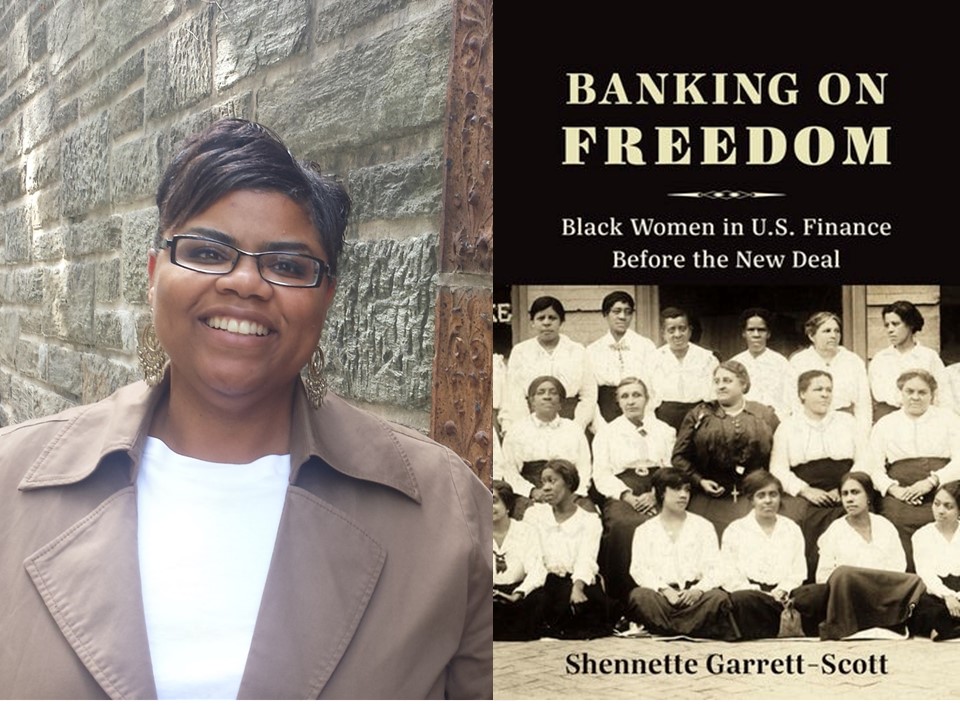

Schuessler discusses the leading scholars working in the history of capitalism as well as the new books in the area. The article also mentioned our recently launched series, Columbia Studies in the History of U.S. Capitalism, edited by Louis Hyman, Bethany Moreton, and Julia Ott, all of whom are featured in the article.

More from the article:

The dominant question in American politics today, scholars say, is the relationship between democracy and the capitalist economy. “And to understand capitalism,” said Jonathan Levy, an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and the author of “Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America,” “you’ve got to understand capitalists.”

That doesn’t mean just looking in the executive suite and ledger books, scholars are quick to emphasize. The new work marries hardheaded economic analysis with the insights of social and cultural history, integrating the bosses’-eye view with that of the office drones — and consumers — who power the system.

“I like to call it ‘history from below, all the way to the top,’ ” said Louis Hyman, an assistant professor of labor relations, law and history at Cornell and the author of “Debtor Nation: The History of America in Red Ink.”

The new history of capitalism is less a movement than what proponents call a “cohort”: a loosely linked group of scholars who came of age after the end of the cold war cleared some ideological ground, inspired by work that came before but unbeholden to the questions — like, why didn’t socialism take root in America? — that animated previous generations of labor historians.

Instead of searching for working-class radicalism, they looked at office clerks and entrepreneurs.