International Translation Day

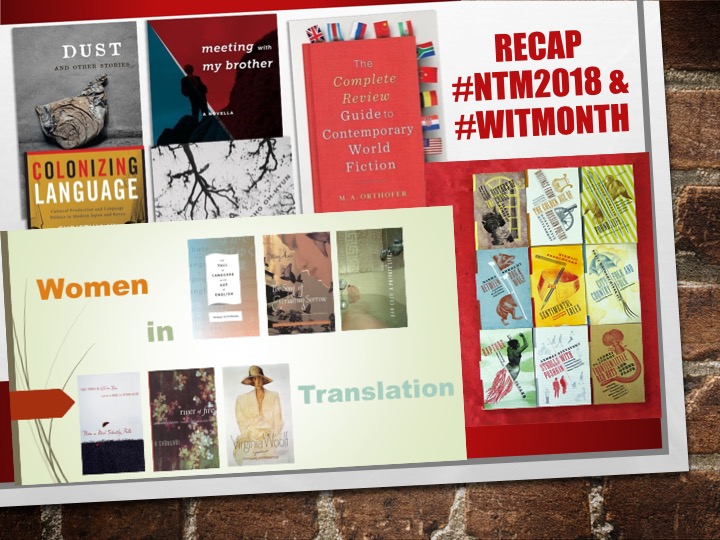

Today, September 30th, isn’t just the last day of National Translation Month it is also International Translation Day. International Translation Day is a day to celebrate language professionals and the work that they do. Here on the Columbia University Press Blog we prominently featured fiction and nonfiction in English translation, as well as scholarly books about language and translation, throughout the month of August for Women in Translation Month and throughout the month of September for National Translation Month.

In a recent post about writing The Complete Review Guide to Contemporary World Fiction, a readers guide to fiction from around the world available in English, author M.A. Orthofer writes: “The disparity is remarkable: the number of works of fiction written in English published annually in the United States alone is in the tens of thousands, compared to only a few hundred new works in translation.” This disparity highlights the important role translators play in bringing works to English language readers. In his post, Orthofer is heartened by the “renewed interest in and enthusiasm in fiction in translation in the English-speaking centers of the world.” We are also heartened by this trend and by the enthusiasm our translators bring to their craft and to the books they bring to new audiences. Today, in honor of International Translation Day, we are going to look back at some of our favorite translation and language posts from the last couple of months.

• • • • • •

Translator, writer, and scholar of Japanese literature John Nathan has had an illustrious career translating works by Yukio Mishima, Natsume Sōseki, and the Nobel Prize winning Kenzaburo Ōe. For Columbia University Press, he translated Sōseki’s final novel, the unfinished masterpiece Light and Dark, and wrote the new biography Sōseki: Modern Japan’s Greatest Novelist. In his post, “A Reluctant Translator,” Nathan reflects back over his long career, the different paths he’s taken, and likens selecting a book to translate to falling in love.

“Reading in the Japanese original I had to feel smitten, unable to bear the thought that Anglophone readers should be deprived of access to such a wondrous piece of writing, to commit to a translation.”

~John Nathan, “A Reluctant Translator”

• • • • • •

Early Soviet era writer Mikhail Zoshchenko is among Russia’s greatest humorists. In a review of the newly translated collection Sentimental Tales, The Economist said: “The only thing harder than cracking jokes may be translating them. Perhaps this is why Mikhail Zoshchenko remains a lesser-known Russian writer among English-language readers.” Boris Dralyuk, the translator of Sentimental Tales, playfully writes about the challenge of translating humor in the post “Poking Jokes,” likening it to “dancing about architecture.”

“If writing about music is like dancing about architecture, then translating humor . . . Well, let’s just say any sane person would rather foxtrot about Postconstructivism. It’s a hard job, often thankless, but, for certain reckless individuals, the challenge proves irresistible. Some texts are just too funny—and too important—not to share.”

~Boris Dralyuk, “Poking Jokes”

• • • • • •

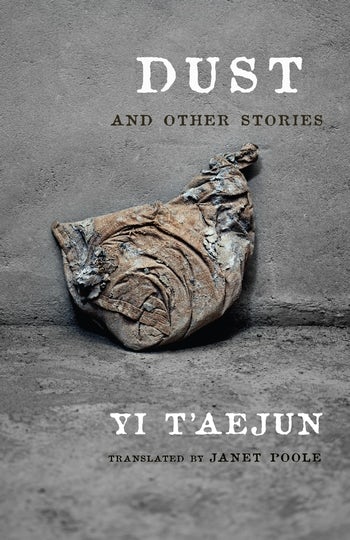

Janet Poole, a scholar of Korean literature, discusses translating the work of Yi T’aejun in the post “Janet Poole on Yi T’aejun and the Literature of Two Koreas.” Yi was one of twentieth-century Korea’s true masters of the short story who stunned his contemporaries by moving to the Soviet-occupied northern zone of his country in 1946. A decision that did not lead him to safe haven, his work eventually was stifled and censored in both North and South Korea until recent years. Poole recently compiled and translated Dust and Other Stories, which collects work from across Yi’s career and across both Koreas.

“Yi himself was a most unlikely candidate to flee from the southern half of the peninsula to the communist north in 1946. A committed dilettante and a dreamer, he believed passionately in literature and art as realms that could nurture the individual.”

~Janet Poole, “Yi T’aejun and the Literature of Two Koreas”

• • • • • •

Sofia Khvoshchinskaya and her sisters, Nadezhda and Praskovya, are often compared to their British contemporaries, the Brontë sisters. An Austen-esque comedy of manners, City Folk and Country Folk offers a unique portrait of a crucial moment in Russian history and literature. As Columbia PhD student Elaine Wilson wrote previously for our blog, much of the comedy in the book comes from one of the male characters’ multiple frustrated attempts to ingratiate himself with the main female characters. A topic that translator Nora Seligman Favorov took up last month for Women in Translation Month in the post “A Nineteenth-Century #MeToo Moment?”

“If City Folk and Country Folk has one overarching theme, it is the nature of power in a time of change.”

~Nora Seligman Favorov, “A Nineteenth Century #MeToo Moment?”

• • • • • •

The philosopher Michel Foucault is a towering figure in twentieth-century French thought. The newly published Foucault at the Movies brings together all of Foucault’s commentary on cinema, some of it available for the first time in English, along with important contemporary analysis and further extensions of this work. The book’s translator, Clare O’Farrell, recently wrote a post about discovering Foucault’s work as a college student and the challenges of translating works of philosophy.

“Translating European philosophy in general also takes place within the context of ongoing debates about whether to opt for a transliteration which retains some of the features (and perhaps nuances) of the original source language or to opt for a style that sounds more natural in English.”

~Clare O’Farrell, “On Translating Foucault at the Movies”

• • • • • •

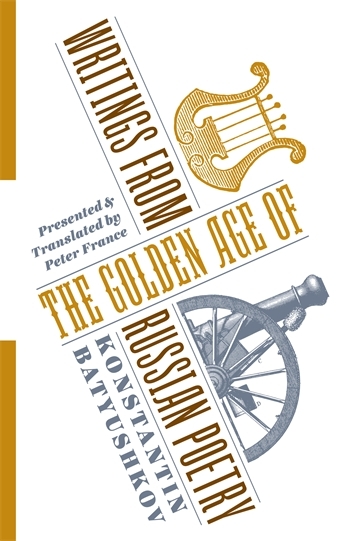

Translator Peter France, who has translated the works of Osip Mandelstam, Yevgeny Baratynsky, and others, wrote a post about the poet Konstantin Batyushkov, whose work France translates and presents in the genre-defying book Writings from the Golden Age of Russian Poetry, which blends biography and anthology. Batyushkov is considered one of the great poets of Russia’s Golden Age, a poet Pushkin said “did for the Russian language what Petrarch did for Italian.”

“It’s a moving story, with a brilliant, idiosyncratic, tragic hero – who is above all a poet. Worryingly for his translator, his verse was praised by contemporaries for its sonorous beauty.”

~Peter France, “On the Poet Konstantin Batyushkov”

• • • • • •

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki is one of the most important Japanese writers of the twentieth-century. The year 1928 was a remarkable one for Tanizaki. He wrote three exquisite novels, but while two of them—Some Prefer Nettles and Quicksand—became famous, the novel In Black and White disappeared from view and was nearly forgotten. A sophisticated psychological and metafictional mystery, In Black and White is a literary whodunit that blurs the line between fiction and reality. Translator and scholar of Japanese literature Phyllis I. Lyons wrote a post about Tanizaki, his work, and discovering his forgotten novel.

“The thought that there might be a Tanizaki novel that I had never heard of—had never even seen mentioned in the voluminous Japanese critical literature about this towering figure—was inconceivable.”

~Phyllis Lyons, “On Translating An Unknown Novel: Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s In Black and White”

• • • • • •

Peruse all of our posts from Women in Translation Month and National Translation Month for more from our authors and translators, not to mention a smorgasbord of excerpts of books from around the world and across genres.