Becoming Vermin Perhat Tursun as a Franz Kafka Character

Darren Byler

The imprisoned Uyghur author and poet Perhat Tursun hates it when people call him “the Uyghur Franz Kafka.” He thinks Uyghur writers should be recognized as world-class intellectuals on their own terms, not as derivative world literature representatives of a Turkic Muslim people in Northwest China. At the very least, they should be seen as the present instantiation of the great Sufi poets of the Uyghur past. Yet it is hard not to compare him to Kafka or other great writers of estrangement and paranoia. Until 2018, Tursun—like Kafka—was a pencil-pushing bureaucrat by day and an observer of urban machinery and madness by night.

Reading an unpublished confessional poem, “Franz Kafka,” that Tursun wrote nearly two decades ago, it is clear that at one point Tursun did find in Kafka a source of inspiration. He writes:

Kafka often overheard

the lamentations of the land and the outcries of the sun,

sounds which no one else could hear,

since no one could have been equally as depressed.

After overhearing those same sounds

I used to imagine becoming a writer like Kafka, too

but I just became one of his characters.

Tursun was a Kafka character tucked away in a government office in Urumchi. He never left the nation of his birth, and his many novels and collections of poetry remain largely unread outside of Northwest China. Then, in 2018, he was detained as part of China’s great purge of Uyghur cultural figures whom state authorities deemed a member of the “three forces”: ethnic separatism, religious extremism, and violent terrorism. A year later he was reportedly sentenced to sixteen years in prison, joining the more than five hundred thousand people who have been formally prosecuted in the Uyghur homeland over the past five years.

Despite this—and because of this—Tursun demands our attention. Before he disappeared, he pushed me again and again to publish translations of his novels and poems. This also, Tursun notes in his poem to Kafka, is an important difference:

Before he died, Franz Kafka made

a friend promise

to burn all his manuscripts to

prevent the exposure of his secrets to strangers,

but his friend betrayed him.

Tursun asked me for the opposite, and for a time I betrayed him, hoping to protect him and my cotranslator A. from further scrutiny from a Chinese state wary of any Uyghur who dared to express independent thoughts, particularly in an international context. But he wanted me to expose the secrets of his art to the world. And after he was taken and sentenced, and my cotranslator disappeared, it seemed clear that now was the time for his work to be known to the broader world.

His novel, The Backstreets, which has just been published in English, tells the story of an unnamed Uyghur young man who moves to the Han Chinese–majority capital Ürümchi in the Uyghur homeland, known in Chinese as Xinjiang, in search of work. He finds a temporary position in a government office, but his loathsome, perpetually smiling boss does everything in his power to make sure that he cannot have a place to call his own. The boss, his coworkers, the janitorial staff, and the strangers he meets on the street collectively conspire to push him away, mocking his Mandarin elocution, his appearance, and more, all evidence of his lack of value to them.

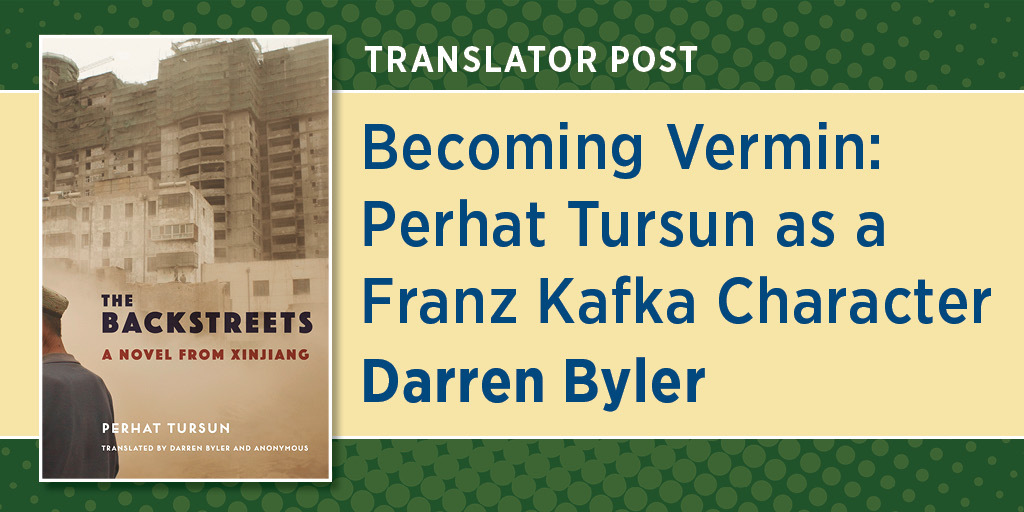

“The Three Forces” Are Rats in the Street; Together We Will Chase Them Down “三股势力” 过街老鼠人人喊打, propaganda mural, Xinjiang, China. (Courtesy of the Xinjiang Documentation Project)

Over the course of the novel, the protagonist begins to understand that the people around him look at him much like how they look at the rodents and other vermin scurrying through Ürümchi’s gutters. At the same time, he realizes that though he is disoriented by the urban landscape and the overwhelming smog of the city, he possesses a heightened sense of smell. It is as if he can sense the presence of festering disease in the streets that everyone around him cannot. He also comes to believe that numbers he finds on scraps of paper and the sides of buildings can help him solve the mystery of his place within the city and, more profoundly, the universe. The novel pulses with these numbers, drawing readers into the mystery of the protagonist’s life and the way Uyghurs more generally have been pushed into a position of scorn and dehumanization within Chinese society.

Ultimately, The Backstreets is a portrait of life in the madness of colonization, of ethnic difference racialized, of families torn apart by depression and alcoholism, and of living under the shadow of portraits of Mao Zedong. It is also suffused with absurdist humor and great beauty that comes from a wellspring of Uyghur creative thinking and tradition. Using a poet’s imagistic eye, Tursun shows ways of seeing and inhabiting the world that pull the sacred, intimate traditions of Uyghur villages and shrines into the mundane present of an urban Chinese settler city. Perhaps this is why Gary Shteyngart wrote after reading the book that Tursun’s prose was “worthy of Kafka’s.” Tursun writes about the absurdities of urban indifference and marginalization in his own voice, as if he were a Kafka character, but in a world that is wholly of his own community’s making. The colonization of the Uyghurs and their refusal of it—the process that Tursun conjures—is singular.

Tursun has a uniquely gifted mind. Ever since he published his first Uyghur-language poem at the age of eleven, he has been devouring literature and philosophy. He learned Chinese so he could read Freud and Schopenhauer in translation. Then he learned English so he could read Faulkner and Nabokov in the original. Name a philosopher, writer, or poet and he will give you a detailed analysis of their work. The inspiration for his work on madness comes from his reading of Foucault, Lacan, and the verses of seventeenth-century Sufi dervishes, written in the old Turkic language Chagatay. Tursun brings the voices of those Sufi friends of the universe into the present. And he demands that readers not forget him or the circumstances that have thrown him and hundreds of thousands of other Uyghurs—who state authorities and settler Han view as vermin—into internment camps, prisons, and locked factories. Reprising a verse from The Twelve Muqam, the epic poems of the Uyghurs, Tursun ends his Kafka confession with the following lines:

Please tell anyone who asks, “Where is Perhat Tursun?”

that he is in the well,

and that his companions are snakes and scorpions…

Darren Byler is assistant professor of international studies at Simon Fraser University. He is the cotranslator of The Backstreets: A Novel from Xinjiang.