Q&A: Ariel Rogers on On the Screen

“There is no other book remotely like this. On the Screen is original in the material it unearths and discusses, offering an innovative history of film and technology. It strikes an easy balance between big ideas and focused analysis, addressing unmapped screen dynamics as crucial elements of cinema.”

~ Haidee Wasson, author of Museum Movies: The Museum of Modern Art and the Birth of Art Cinema

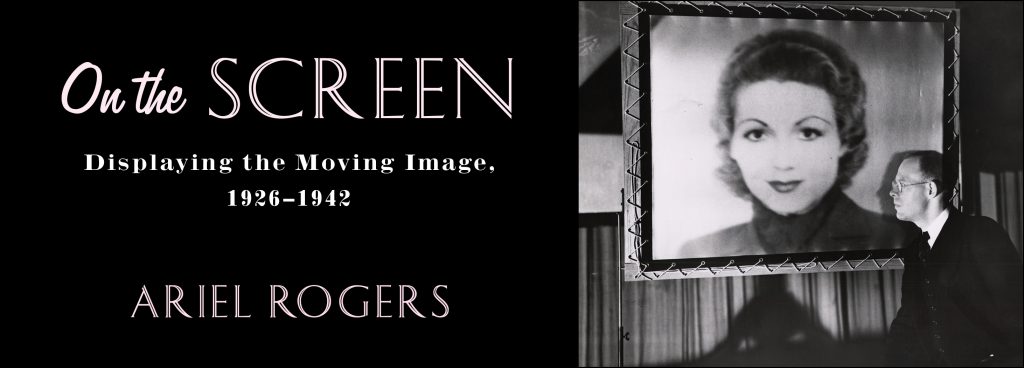

In the world of digital technology and new media, screens have become a part of daily life. Discussion of these screens tends to focus on what is being displayed, but Ariel Rogers, author of On the Screen: Displaying the Moving Image, 1926-1942, shifts the focus to consider the history and various approaches to the use of the screen itself. In this Q&A, Rogers shares the significance of screens and what we could learn from the study of them.

Enter this week’s book giveaway drawing for a chance to win a copy of On the Screen!

• • • • • •

Q: Why write a book on screens?

Ariel Rogers: It has become commonplace to invoke the pervasiveness of screens to describe the contemporary media landscape. When we talk about how much time we spend on screens, we are often referring to our engagement with screen-based phenomena like social media or video games. But we are also acknowledging the ubiquity of a material object that ties together devices such as mobile phones, computers, and televisions and appears to be significantly shaping our experience of the world. One of the things that is interesting about this contemporary situation is that it draws attention to an object—the screen—that has a long history but also a long history of being ignored. In discussing historical cinema, for instance, we’re used to focusing on the films projected on the screen, or the viewers and situations in front of and surrounding the screen, and very seldom on the screen itself. My book uses the current visibility of screens as an inspiration to explore how screens have long shaped people’s experience of media and, through media, the world. To do that, I focus on how screens functioned in film and the then-emergent medium of television in the United States in and around the 1930s, the height of the era of what is often termed “classical” Hollywood cinema.

Q: What does this attention to screens reveal about Hollywood cinema in the classical era?

AR: In discussing the current pervasiveness of screens, people often assert how different the contemporary situation is from the classical era, when it is assumed that moving images were encountered predominantly as cinema and that cinema was encountered on big screens in theaters. But in researching the use of screens in that period, it becomes clear that screen practices were a lot more diverse than is usually assumed and, in fact, involved several of the phenomena often associated with contemporary media, such as small screens, mobile screens, and multiple screens, revealing close connections between cinema and nascent forms of television. My book demonstrates how the use of screens in film and television during the classical era contributed to particular constructions of space, especially the effort to synthesize and even synchronize the spaces on and around the screen surface. This approach highlights links between filmmaking and exhibition and shows how Hollywood cinema collaborated with what are often considered alternate forms—such as avant-garde and nontheatrical cinemas as well as television—in shaping modern modes of experience.

Q: How does the focus on screens help us to understand cinema’s social dimensions around the 1930s?

AR: An exploration of cinematic screen practices highlights the spatial organization of both films and the places in which they were shown in that period. These forms of spatial organization simultaneously reflected and contributed to particular social formations, including particular constructions of race, gender, and nation. For instance, I write about the use of rear-projection screens on Hollywood soundstages, which made it possible to composite live-action footage with previously filmed backgrounds, and I argue that the use of this special-effects technique contributed to the way Hollywood cinema presented racial difference in the 1930s. Especially though not exclusively in Westerns, the use of rear-projection screens contributed to the racial segregation of onscreen space, physically separating white protagonists from racially othered characters consigned to background landscapes. In such cases, parsing how the rear-projection screen worked to link, distinguish, and demarcate different spaces within the fictional world can also illuminate the ways in which cinema has reinforced and perpetuated constructions of racial difference in the actual world.

Q: What does this examination of historical screen practices tell us about the contemporary media landscape and the ubiquity of contemporary screens?

AR: By moving away from a focus on assumed material differences between historical and contemporary screens (such as large/small, static/mobile, or single/multiple), we can also move away from some common assessments of contemporary media, such as ideas that ubiquitous screens are making us more distracted and our lives more fragmented, which ignore the forms of distraction and fragmentation long associated with media and thus don’t really tell us much about the contemporary situation. In parsing the ways screens have contributed – and continue to contribute – to particular spatial formations, more concrete distinctions come into relief. In particular, recognizing how screen practices in and around the 1930s worked to synthesize and synchronize spaces also makes it clear that contemporary screen practices often perform a different function. In the book’s coda, which explores contemporary practices with a focus on virtual reality, I argue that such current uses of the screen no longer function primarily to create new spaces but instead work to make visible obscured layers of mediation within our existing everyday spaces.

Explore more books in the Film and Culture Series, and save 30% when your order from our website by using coupon code: CUP30 at checkout!