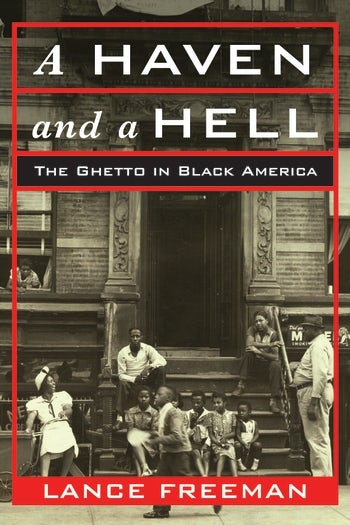

Lance Freeman on A Haven and a Hell: The Ghetto in Black America

“A Haven and a Hell is a highly-accessible and necessary book for a broader and richer understanding of urban Black America.”

~Marcus Anthony Hunter, coauthor of Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life

Today we are featuring a guest post from Lance Freeman, a professor in the Urban Planning Program in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University. His newest book, A Haven and a Hell: The Ghetto in Black America is available for pre-order now, but you can enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy for free.

• • • • • •

A Haven and a Hell: The Ghetto in Black America chronicles the role of the ghetto as an institution in black life since the late 19th century, reflecting my long standing interest in the origins and fates of black neighborhoods. As a New York City kid in the 1970s and 1980s my fascination with black neighborhoods was fueled by the invisible yet seemingly impervious boundaries that separated neighborhoods by race. There were distinct “black” neighborhoods and distinct “white” ones. Even Flushing, Queens, where I spent most of my childhood, which at the time was a diverse area, was hardly a melting pot. Instead, while Flushing as a whole was very diverse, at the block level or even by buildings, Flushing was starkly divided by race. Certain blocks and buildings, were the almost exclusive domain of one group or another.

Beyond fascination, these patterns of segregation disturbed me—for the spaces occupied by blacks, with a few exceptions, always had more crime, worse housing, and fewer stores and amenities. My parents recognized these stark disparities too. My mother, a native of Harlem, sought to escape the ghetto and move to neighborhoods with the best amenities she could afford, even if this meant moving into predominantly white neighborhoods. My father, however, was skeptical of the benefits of living among white folks and didn’t want to lose the community he knew from living in Harlem. When they divorced, he returned to Harlem, the neighborhood of his childhood.

“Beyond fascination, these patterns of segregation disturbed me—for the spaces occupied by blacks, with a few exceptions, always had more crime, worse housing, and fewer stores and amenities.”

The two-sided nature of the ghetto, as a place my mother strove to escape, but one my father fled back to, was something that became more apparent as I pursued a career first as a professional urban planner and then as an academic planner and urbanist. I wanted to understand how and why some neighborhoods, often black ones, were considered dangerous and disadvantaged, and what could be done to improve conditions there.

My concern and curiosity about black neighborhoods has animated my research agenda since graduate school and led to my first book, There Goes the Hood, where I studied how gentrification was impacting residents in two predominantly black neighborhoods.

My research on gentrification confirmed what many observers have undoubtedly noticed, long term residents of gentrifying neighborhoods cherish their neighborhoods and value these spaces. The feelings expressed to me by residents of gentrifying neighborhoods, which in many ways mirrored those of my father, kindled an interest in learning more about how blacks viewed the ghetto in the past. I wanted to explore how residents of the ghetto and the race in general felt about the ghetto. How did blacks feel about the experience of ghettoization? I was interested in how these feelings evolved over time from the early years of the ghetto around the turn of the last century to today.

“The ghetto was often a hell, as the use of the term as a derogatory adjective today implies, but it was also a haven at times.”

Answering “how blacks experienced the ghetto” across time, posed a challenge. Unlike my work on gentrification, where I could interview residents currently living in gentrifying neighborhoods, interviewing early 20th century residents of the ghetto would be impossible. Instead I considered a variety of sources, art, fiction and nonfiction books, black newspapers, popular magazines and the actions of people themselves. Artists depicted the ghetto as a prison they longed to escape and also a promised land they dreamed of. Newspapers chronicled the experiences of everyday folks and elites alike. And people voted with their feet, moving to and from the ghetto and in doing so revealing just what they thought of the ghetto as a place.

The stories told by these multifaceted sources form the basis of A Haven and a Hell, and this story is that of a duality. The ghetto was often a hell, as the use of the term as a derogatory adjective today implies, but it was also a haven at times. The book traces the waxing and waning of the ghetto as a haven and a hell and the forces that shaped this duality. The ghetto’s dual roles in black life in parallels the aforementioned schism that captured my parents’ conflicting ideas about where to live, and in some ways depicts the “twoness” of black life in America that W.E.B. DuBois wrote about over a century ago. The ghetto as a haven for the black community and a source of black culture, but also a hell, and a reminder of black’s otherness and exclusion from in American society. A Haven and a Hell tells this story and helps provide a more complete picture of the role of the ghetto in black life.