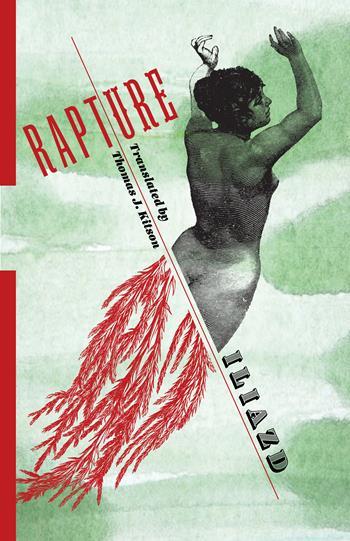

Thoughts on Rapture by Iliazd (Ilia Zdanevich)

Iliazd’s Rapture is one of the upcoming titles in the Russian Library, a new series that seeks to demonstrate the breadth, variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition to English-language readership through new and revised translations of premodern, modern, and contemporary Russian literature.

Today Veniamin Gushchin, CC ’18, Russian Library Intern responds to Rapture by Iliazd, translated by Thomas J. Kitson

The term emigrant, as opposed to the more commonly used immigrant, is inherently backwards facing, focusing on the country of origin rather than the destination. In the popular imagination, the immigrant arrives in a land of opportunity, while the emigrant flees from an oppressive regime, hopelessly yearning to return to their past. Though the two words have vaguely the same meaning, though the distinction in writing is but a few letters and in pronunciation is often barely detectable, the terms are antonyms due to the complex set of relationships an individual has with their countries of departure and arrival.

As the son of Russian immigrants that grew up in a bilingual and bicultural environment, I am very sensitive to this distinction. My parents immigrated to the United States in the 90s for greater job opportunities in the field of medicine and made the deliberate choice – mostly to spite my grandmother, who believed such efforts to be in vain – to raise me speaking Russian and aware of my cultural heritage. From watching the Soviet version of Winnie the Pooh before Disney’s to listening to tapes of the actor Innokenty Smoktunovsky reading Eugene Onegin on road trips, my parents recreated a small island of Russian culture in our home. They spoke of their Soviet past with a mixture of nostalgia and disillusionment, as many Russians do. My childhood experience was one of continually balancing my parents’ past with the pressures to assimilate to American culture. Living in suburban Maryland rather than in an immigrant enclave like Brighton Beach, my sole source for my Russian identity was my parents, my only chance to use my Russian my home. As a result, preserving this heritage grew in significance. Now, studying Russian literature in college, I seem to have come to some sort of compromise between these identities. Nevertheless, I do often feel as if I am still that child coming back from school to my parent’s home, part of and distant from both worlds. More importantly, my experience is different than those of denizens of Brighton, than those whose heritage becomes but a percentage mentioned in discussions of ethnic background.

To turn things back a century, and three waves of Russian migration, the tension between cultural preservation and assimilation is reflected in the most prolific Russian émigré writers, Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov. Especially in the works of the nomadic Nabokov, nostalgia for an idealized version of prerevolutionary Russia is central to the artist’s identity. In terms of assimilation, even in Paris, Bunin wrote exclusively in Russian and interacted mostly with his immediate circle of fellow emigrants. Though Nabokov appears to have shown a greater degree of adaptability, becoming internationally renowned as a writer in English, his constant relocation – the only “Nabokov house” is in St. Petersburg where his family lived before the Revolution – betrays his inability to settle down and fully reconcile his lost past with the present. The idealization of this prerevolutionary period has influenced perceptions of the Soviet Union and imperial Russia both abroad and in Russia. More recently, post-Soviet discourse, exemplified in artistic expression such as Govorukhin’s film “Russia That We’ve Lost,” returns to portraying the turn of the twentieth century as a time of cultural brilliance and sophistication. These notions about the first wave of Russian immigration and that era have become so widespread that they have come to represent its dominant narrative.

The figure of Ilia Zdanevich, or Iliazd, complicates this simplistic view of the reactionary emigrant. Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, his first act of migration was to Petrograd, where he became involved in a number of avant-garde artistic groups associated with the movement of Russian Futurism. His reason for migrating to Paris was to establish new artistic relationships between the nascent Soviet avant-garde and similar artistic movements in Paris, such as Dada and surrealism. Both political and artistic, he stands in contrast to the more conservation Nabokov and Bunin. While the latter two writers proudly continued the traditions of Russian nineteenth century literature, Zdanevich eagerly embraced the possibility of reshaping and developing his genre. Despite his efforts, however, once the Soviet government turned against the avant-garde, Iliazd found himself in “poetic reclusion,” effectively exiled despite having emigrating for an entirely different set of reasons. Nevertheless, the artist continued to live in Paris, collaborating with the likes of Picasso, Matisse, and Léger, developing a reputation in the European art world and, at least in part, assimilating.

Rapture is a doubly nostalgic novel, set in Iliazd’s native Georgia and written as an allegory of the Russian Futurism movement. Published in a doubly distant Paris, it is a thick mixture of avant-garde and traditional folklore, of Russian, Georgian, and Western influences that is impossible to fully separate into its constituent elements.

This new translation of Rapture allows Anglophone readers to experience Iliazd’s complex and thrilling artistic vision for the first time ever. In addition to placing the novel on the same shelf as the modernist masterpieces of Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Thomas Mann, the publication of this translation complicates the simplistic binary between emigrant and home country present in the most influential narratives about this era. Iliazd’s voice joins the already dominant voices of Bunin and Nabokov to paint a more detailed and nuanced portrait of the first wave of Russian immigration in Paris. Immigration, emigration, and migration are all messy concepts, crossing the boundaries of identity as much as geopolitical borders. Each individual within these processes has a unique relationship to both the country of arrival and departure, the experience only able to be captured in polyphony.

Want to learn more about Rapture? Join the event TODAY, May 4, cosponsored by the NYU Jordan Center and PEN America World Voices Festival, with translator Thomas Kitson and scholar Jennifer Wilson. “What’s Old is New: Gender and Power in Iliazd’s Neglected Rapture”