A Stratum of Sadness That Abides

David Hajdu

One hundred and one years ago, in February 1921, Bert Williams proposed something more radical than it should have been. Williams, a three-decade veteran of the stage at age forty-six, had risen from the woolly ranks of Barbary Coast honky-tonks and minstrel shows to become acclaimed as one of the most gifted comic actors and singers in the history of American entertainment. A major attraction in vaudeville and the first Black star to be featured in the Ziegfeld Follies, Williams was touring the country in a road-company copy of the Follies called the Broadway Brevities when the Boston Globe interviewed him, ostensibly to promote the show’s arrival in town. What Williams gave them was not so much promotion as it was provocation.

“I shuffle onto the stage not as myself, but as a lazy, slow-going Negro,” Williams told the interviewer in the unsigned article, no doubt written by a white reporter. Williams, a Bahaman-born Black man, had long performed solely in blackface—in part for the opportunity to perform at all in a time when horrific antebellum-era racism was standard practice in American show business, and in part as a way to soften, to elevate, and to humanize the theatrical presentation of Black life, usurping white minstrel performers’ claim to the right to define Blackness. “The real Bert Williams is crouched deep inside the coon who sings the songs and tells the stories,” Williams continued.

Some writers of the day grasped that Williams’s performance of a racist stereotype—less demeaning than a white minstrel’s “coon” act, certainly, but one still grounded in the belittling and oppressive lies of white supremacy—was work of refined theatrical skill. As a critic for The Washington Post wrote in a review of Broadway Brevities, “The art of Bert Williams is founded on constructive characterization. The slow, ambling gait, the balanced intonation, the emphasizing gesture, the impressive pause, all have their place in making a reality of the man he is portraying. He looks on each character he plays as a separate person, and plays it only after the most painstaking and careful study.”

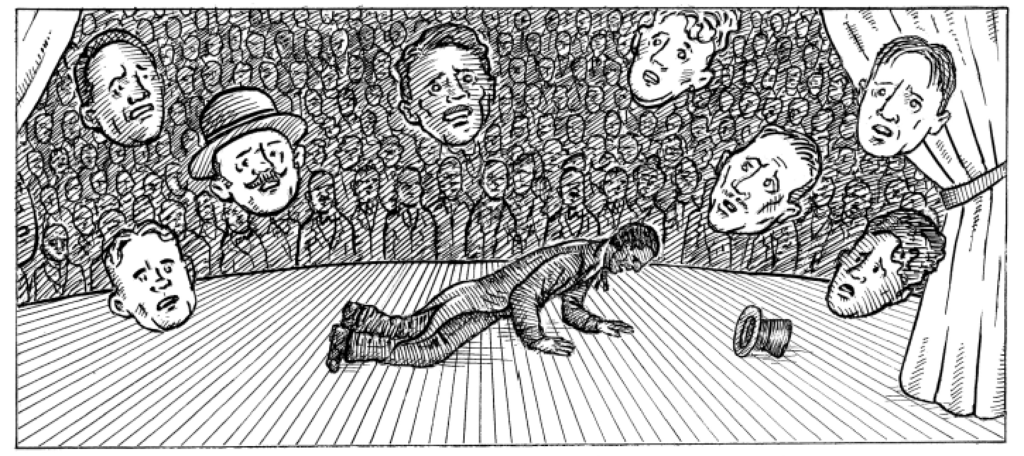

Art: John Carey, from A Revolution in Three Acts

Still, Williams longed to do more—he wanted more, worked for more, and knew he deserved more. In his interview for the Boston Globe that day in February, he laid out a bold vision for both his future as an artist and the future of Black art. “Now that I have realized all my early ambitions to amuse and entertain, I’d like to do something a little different,” Williams said. “I know I can make them laugh. Now I want to show that I can make them cry.”

“I’d like (to do) a piece that would give me the opportunity to express the whole of the Negro’s character. The laughter I have caused is only on the surface. Now I’d like to go much deeper and show there are depths that few understand as yet. I’d like to interpret a character written by one of our race [because] when we write we have little comedy. Deep down in the race, with all its carefree ways, is a stratum of sadness that abides.”

“If I could interpret in the theater that underlying tragedy of the race, I feel that we would be better known and better understood. Perhaps the time will come when that dream will come true. I will never cease to hope that it will.”

While Broadway Brevities was still touring, Williams made plans to appear next in a musical farce originally titled The Pink Slip and renamed Under the Bamboo Tree. Williams, the star of the production, played a hotel worker. It was a comic role, but one laced with pathos. “I’m a porter in the hotel at Catalina Island, an awful liar, but a character,” he told a journalist.

Williams was understood to have personally selected the Black composer Will H. Vodery to write the music. In collaboration with the librettist Walter De Leon, Vodery crafted a seriocomic lament for Williams to deliver as his showpiece: “Puppy Dog.”

When folks look at you

The first they do

is to laugh

You ain’t comical but

You is such a mutt

They just laugh

Your earses and your pawses, too

Don’t look they was meant for you

The reason I like you’s because

You remind me of me, I’m telling true

Under the Bamboo Tree previewed in Cincinnati and moved to Chicago, then Detroit before a planned opening on Broadway. Williams’s woeful reading of “Puppy Dog” was an unexpected, unconventional showstopper: “a gem of artful acting that inspires much laughter and that at the same time brings the listener close to tears,” in the words of the Detroit critic Al Weeks.

On February 27, 1922, Bert Williams finished singing “Puppy Dog” and, with half of the show left to perform, collapsed. He had been suffering from heart disease, compounded by overwork, and contracted pneumonia that went untreated in Detroit. Transported by train back to his home in New York, Williams died on March 4, a century ago this year. He was laid to rest in a Harlem church, where an estimated 5,000 mourners of all races were reported to have viewed his casket. Another 10,000 waited outdoors in the rain, abiding by the sadness that Williams embodied in life as well as death.

David Hajdu is a professor at the Columbia Journalism School and coauthor of A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay, and Julian Eltinge.

Related Posts

-

-

African American / Black Studies / American History / American Sociological Association / Author-Editor Post/Op-Ed / Black History Month / History / Human Rights / International Studies Association / Sociology

African American / Black Studies / American History / American Sociological Association / Author-Editor Post/Op-Ed / Black History Month / History / Human Rights / International Studies Association / SociologyReconceptualizing Justice for the Victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Nicole Iturriaga

-

-

-

-

-

-