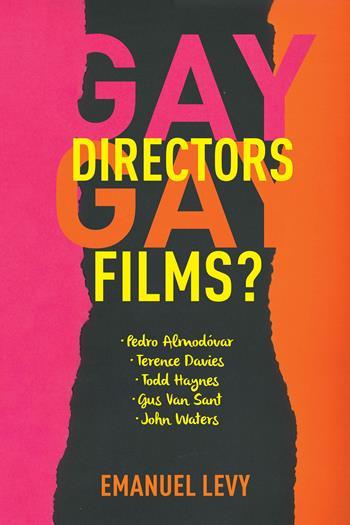

Emanuel Levy on the Politics of Gay Films

“All five filmmakers have spoken against reductionism—namely, the reduction of gay artists (and gay screen characters) to sexuality as the single, or most prominent, aspect that defines their personalities.”—Emanuel Levy

In the following excerpt from the conclusion of Gay Directors, Gay Films?: Pedro Almodóvar, Terence Davies, Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, John Waters, Emanuel Levy examines the political aspects of the directors’ work and their influences:

All five filmmakers have spoken against reductionism—namely, the reduction of gay artists (and gay screen characters) to sexuality as the single, or most prominent, aspect that defines their personalities. They have also refused to reproduce dominant stereotypes of homosexuals, such as the Sissy, the Suicidal Youth, the Gay Psychopath, the Seductive Androgyne, and the Bisexual. Instead, they have tried to present “more real” or “realistic” gay men and lesbians. They realize, as Anneke Smelik has suggested, that for straight viewers, using old, negative stereotypes confirms prejudice and that for gay spectators, their use might encourage fear, self-hatred, and anger. On the other hand, these directors also realize that presenting only positive images is not the solution and that images of gays and lesbians cannot be seen as simply “true” or “false.” Gay Directors, Gay Films? has focused on the social contexts and the conditions under which various entertainment institutions have created, maintained, and perpetuated ideological and cinematic stereotypes that gay directors have set out to challenge and abolish.

Aiming to establish connections between gays and other marginalized minorities, Haynes destabilizes the division between dominant and subordinate individuals by disturbing the usual space allotted to “others” in society’s broader structure. Like Almodóvar, he avoids any form of labeling because labeling permits those in power to feel secure and to perpetuate the status quo by drawing boundaries that separate those who have from those who have not. Moreover, to label is to judge, and to judge is to limit the range of possibilities of his characters and the range of interpretations of his viewers. No character in his films can be adequately understood or fully contained through sexual labeling; in most cases, socioeconomic status is more important as a defining criterion. He empowers his disenfranchised individuals in fantasy worlds, which they create apart from their oppressors. In Poison, nothing that the jail’s wardens do can prevent the prisoners from engaging in imaginative sexual intercourse (a plot device that served as a climax in Martin Sherman’s Holocaust drama, Bent). In Velvet Goldmine, Arthur rehearses in his imagination the bold declaration of his sexuality to his parents.

Haynes qualifies as a queer filmmaker in the traditional as well as the new sense of the term. As Justin Wyatt has suggested, Haynes’s oeuvre is queer by being unusual, strange, and disturbing, but in my view, it’s also queer in its deconstruction of gay identities and its reconstruction of gay subcultures. His formal experimentation is based on his belief that the greatest function of film (and any art) is to provoke, to disturb, and to unsettle. Like Almodóvar (and David Lynch before him), by making the familiar unfamiliar and the ordinary extraordinary, Haynes has helped viewers see the unusual yet still beautiful elements in our everyday lives.

Four of the five directors (the exception is Van Sant) have dissected the screen role of the housewife, working-class and middle-class, Spanish, British, and American. Almodóvar said early on in his career, “If I want a heroine, I prefer a housewife, whose world is much more interesting as a social commentary as well as melodrama,” though he admitted that every class and group (including yuppies) has its charms and eccentricities. His preoccupation with the role of the housewife reflects his own background, a rural family with a strong matriarch moving to the metropolis and fighting for survival. Years later he acknowledged the impact of similarly themed Italian neorealist features—specifically, Rocco and His Brothers, Luchino Visconti’s 1960 masterpiece. “I tried to adopt a sort of revamped neorealism with a central character that’s always interested me: the housewife and victim of consumer society.”

More than other directors, Almodóvar and Haynes have exposed the sociocultural mechanisms that construct gender roles, but they have done it in different ways. A postmodern intellectual, Haynes has dissected gender analytically from a deconstructive academic standpoint, whereas Almodóvar has done it more intuitively. Both directors have struck a blow against the monolithic accumulation of patriarchal film conventions by critiquing gender stereotypes, but Haynes has done it via serious melodramas, whereas Almodóvar has tackled those issues in various genres: satires, farces, comedies, melodramas, film noir, and even horror-thrillers.

The family institution has been of central concern to all five directors. “As a subject, the family never fails and never disappoints,” Almodóvar said. “I found that when I shot What Have I Done to Deserve This? people began looking at me with different eyes, sort of ‘he’s modern but also sensible.’ The family is always first-rate dramatic material.” Though phrased differently, Van Sant has expressed a similar opinion: “Families are interesting stuff. The dynamics of whatever family you have is an orientation that you apply to the outside world. Maybe it’s just the most interesting thing that I know.”

Van Sant and Haynes have not said much about the impact of their birth mothers on their lives and careers, but Almodóvar, Davies, and Waters have, and Almodóvar’s worship of his mother is also reflected in his casting her in major roles in his pictures until she died. In his features, Almodóvar has analyzed the complex dynamics of three-generational families, a clan absent from most American films (and reality). Reflecting his own background and the family tradition in Spain, extended families, including patriarchal and matriarchal grandparents, abound in his oeuvre.

There is also more concern with the relationships between siblings, be they two brothers, two sisters, or brother and sister, He acknowledged: “I love the sense of fraternity, and I have always enjoyed movies with siblings. Warren Beatty being beaten up in the parking lot for watching his sister’s loss of honor in Splendor in the Grass. . . . Thrilling Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas and his silent visit to brother Dean Stockwell.” And he does not shy away from depicting the camaraderie between female siblings (Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! and The Flower of My Secret) as well as the rivalry between male siblings (most manifest in What Have I Done to Deserve This? and Bad Education).

Van Sant’s work differs radically from that of Almodóvar (and Waters) in that his protagonists either are products of broken families or have no biological families at all. On one level, My Own Private Idaho is the sad tale of two surrogate brothers in search of a missing mother. For Van Sant, newly formed families, based on shared lifestyle or occupation, are far more significant than birth families. In Mala Noche, the Mexican drifters form sort of a community of hustlers. In Drugstore Cowboy, we meet Bob’s mother only once; and the surrogate family that the four drug addicts establish is far more significant. If families of procreation are seldom seen in Van Sant’s work, it’s because his protagonists are high schoolers or adolescents, too young to have families of their own….

Despite variability of nationality and social class, all five have been influenced, directly or indirectly, by the same artists and filmmakers, which demonstrates the universal power of art. Call it the Anxiety of Influence among gay directors, to borrow Harold Bloom’s concept. I have discussed in some detail the thematic and stylistic impact of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas on the features made by Almodóvar and Haynes. More specifically, the directors have all read in high school or college what Almodóvar has referred to as “the damned poets,” like France’s enfants terribles Arthur Rimbaud and Jean Genet, creators of radical works of literary density. It’s not a coincidence that the directors have all watched and then studied Genet’s Un chant d’amour. Almodóvar recalled: “In high school, we of course didn’t hear about Rimbaud or Genet, but I knew very soon that there was something interesting in them and read them on my own.”

Though none of the quintet has defined himself as an overtly political filmmaker, say, in the sense that Oliver Stone is, they have all engaged in sexual politics—in the power relationships between men and women, men and men, and women and women. Domination and subjugation, freedom and control—these are terms that apply to all of them. Critics of Almodóvar have charged that he makes political references in a frivolous and gratuitous way, to the point of trivializing politics by using it for comedic purposes. Those critics have raised the allusions to Shiite terrorism in Labyrinth of Passion and Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and the war of genocide in the former Yugoslavia in Live Flesh and The Flower of My Secret. In response, Almodóvar has claimed that his target audience, the younger generation in Spain that came of age in the 1980s, is more interested in seeking pleasure and happiness than in politics per se. Challenged to take a clearer political position, he said: “I’ve never been a member of a political party because I need to keep my independence. But I’m very much on the left. In films, it’s not necessary for characters to talk about politics. The politics is implicit in the story.” And though he does not define himself as an overtly political filmmaker, he has readily acknowledged that all of his films “carry a political commentary” and that just exploring the lives of housewives is “already a political statement.”

Along with sexual politics, the political denominator shared by these filmmakers can be called the politics of aesthetics. All five have contributed to the democratization of on-screen representation, taking characters that have been (at best) marginal and putting them center stage. They have taken minority subcultures (racial, sexual, or criminal) and made them more mainstream by creating stories in which homosexuals, transvestites, transgenders, drug addicts, and criminals play the leads, occupying unashamedly and unapologetically the center rather than the periphery of the narrative.

For example, Waters has gone way beyond his heroes—Jack Smith, Andy Warhol, and Paul Morrissey—in redefining the politics of taste. Warhol had placed several of his sexy models and hunky studs (such as Joe Dallesandro) at the center of his films, but it was Waters who made a legitimate star out of the 300-pound transvestite Divine and a household name out of cute if chubby Ricki Lake. Individually and collectively, this quintet has revolutionized film and popular culture by redefining their range and parameters. I doubt that the stage and movie musical versions of Hairspray would have been possible without Waters’s pioneering movie twenty-six years ago. That said, the five directors are not alone and not the first ones—they stand on the shoulders of giants, and credit should be given to such iconic gay figures as Oscar Wilde, Jean Genet, Jean Cocteau, William Burroughs, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and others.