What Charles Brackett Tells Us About the Films of Billy Wilder — Anthony Slide

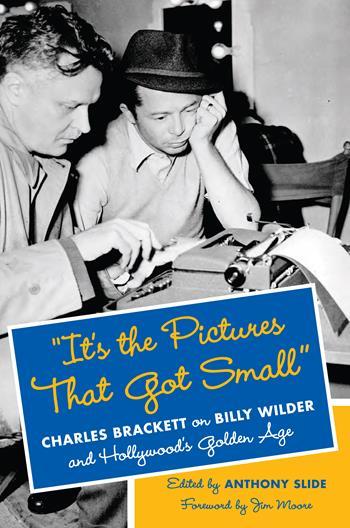

The following essay is by Anthony Slide, editor of “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age. (To save 30% on this book use the discount code SLIITS):

On Sunday, January 11, I introduced a tribute to Charles Brackett, held most appropriately at the Billy Wilder Theatre, located at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. The two films screened that night were The Lost Weekend and Five Graves to Cairo, one very well known and and an Academy Award-winner and the other less so.

It was fascinating to watch these films again with the knowledge of what Brackett had to say about them in his diaries. I strongly recommend that anyone reading the diaries should try to revisit the Brackett/Wilder films. Certainly, one views them in a different light. For example, the first shot in The Lost Weekend is an exterior of Don Birnam’s New York apartment, and thanks to Brackett’s diary entry, we know that the apartment is actually a set built on the roof of Hahn’s Warehouse. Or, every time Doris Dowling, who plays Gloria in film, opens her mouth, one can’t help but think of Brackett’s description of her performance as “amateurish.”

The programming staff at the Billy Wilder Theatre had selected the evening’s films as two that had not been screened recently in Los Angeles. Would my choice have been different? Probably yes. One Brackett and Wilder film that is difficult to see on the big screen in 35mm is The Emperor Waltz, their only Technicolor production and their only musical. It is, in reality, not one of their greatest achievements, but if I saw it again—thanks to the diaries—I would have wondered at the couple’s original casting notion: Greta Garbo opposite Bing Crosby. When I suggested this to the audience at the Billy Wilder Theatre, there was laughter, but would it have been such a bad idea? Garbo was actually enthusiastic, claiming admiration for Crosby, but she was too frightened to face the camera again, and so the role went to Joan Fontaine.

It is now 75 years since Brackett and Wilder made Sunset Blvd., their most famous film, and one that is screened too often in the Los Angeles area for it to make it into the Charles Brackett Tribute. If anything makes the Brackett diaries worthy of publication, it is what he writes about Sunset Blvd. There is so much original documentation here. It is fascinating to read of Wilder and his telling of the movie’s plot to Mary Pickford and jointly deciding as they make their pitch that they just don’t want her for Norma Desmond. How incredible it is that the day before shooting the famous “waxworks” scene of the group of silent stars playing bridge, the second female role had not been cast. Both Theda Bara and Jetta Goudal had been in consideration. Both ladies said no, and, having known Miss Goudal, I can well imagine, as Brackett writes, that she spent half-an-hour on the telephone rejecting his casting call. Ultimately, the afternoon before the scene was shot, Brackett thought of Anna Q. Nilsson, a blonde star of the silent era who was working by then as an extra, and she was a perfect match for the role — her sweetness and waning prettiness at odds with the artificiality of Swanson’s aging, heavily made-up beauty.

Regardless, the two films presented that evening went over well, and emphasized that Brackett and Wilder were a team who naturally complemented each other, regardless of their very different backgrounds and often simmering hostility. I would like to believe that they always maintained a healthy respect for each other, long after they parted company. I know that Brackett never criticized Wilder in public, and I was interested to learn from Larry Mirisch, who was in the audience that night, and whose father, Walter, produced more than a dozen of Wilder’s later films, that Billy never said one word about Brackett.

The diaries speak for themselves—and really they speak for both men.