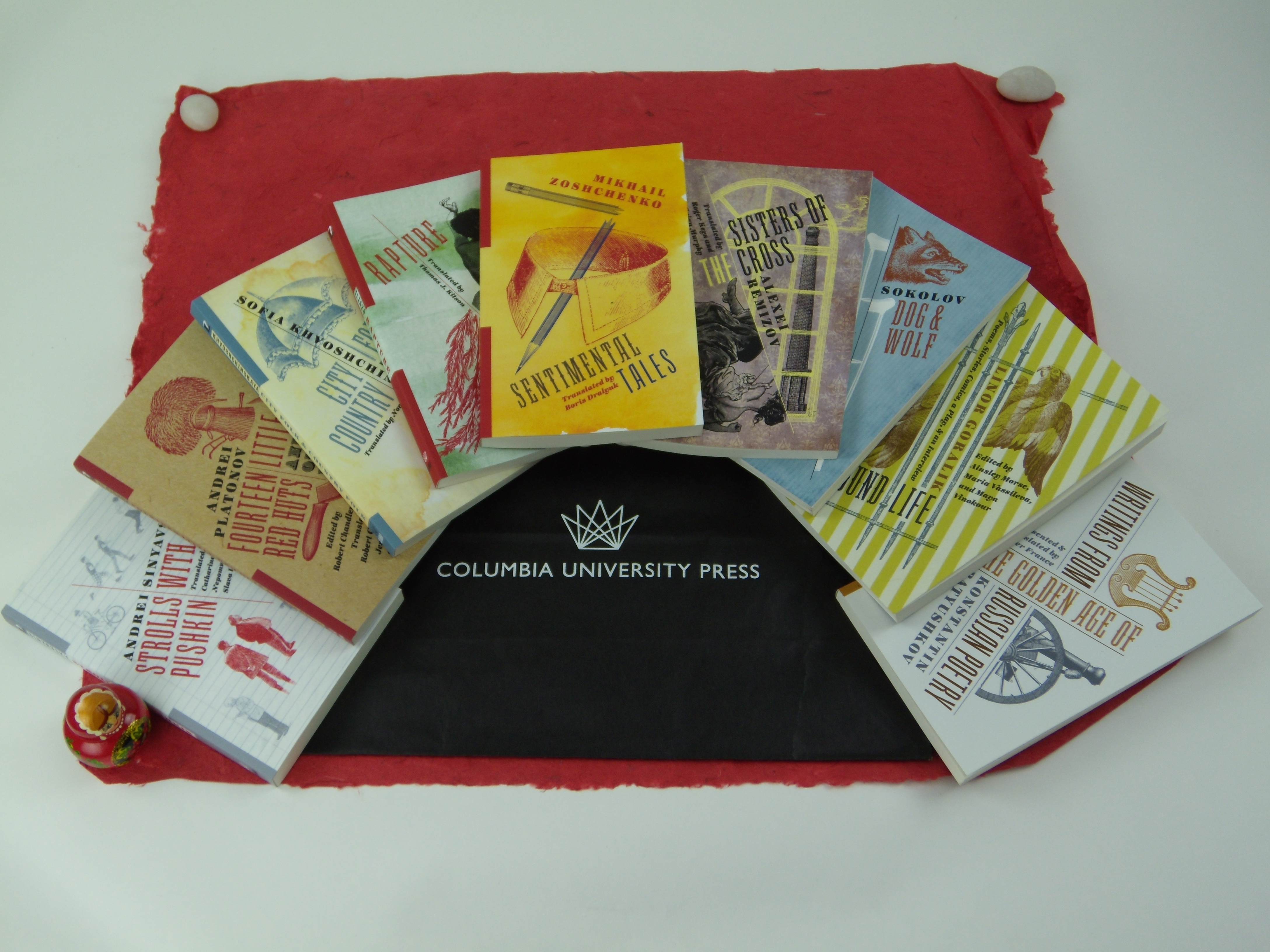

Poking Jokes: On Translating Mikhail Zoshchenko’s “Sentimental Tales”

“Some texts are just too funny—and too important—not to share with an audience that would otherwise have no access to them.”

~ Boris Dralyuk

This week we’ve been featuring Mikhail Zoshchenko’s Sentimental Tales. Now that you’ve had a chance to read the introduction and the prefaces, we thought we’d bring you a “Behind the scenes” look at what it takes to translate humor. Today’s guest blog post comes from the book’s translator Boris Dralyuk, editor of 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (2016) and coeditor of The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (2015).

Remember to enter our drawing to win a free copy of the book!

• • • • • •

If writing about music is like dancing about architecture, then translating humor… Well, let’s just say any sane person would rather foxtrot about Postconstructivism. It’s a hard job, often thankless, but, for certain reckless individuals, the challenge proves irresistible. Some texts are just too funny—and too important—not to share with an audience that would otherwise have no access to them. Sentimental Tales (1923-1936), a tragicomic masterpiece by the great Soviet satirists Mikhail Zoshchenko, is just such a text. We’ll get to its importance in due course. First, the nitty-gritty.

“. . .humor comes in all shapes and sizes and various degrees of dryness. It can be as loud as the clash of cymbals or as understated as a whisper.”

What makes translating humor so difficult? For one thing, humor comes in all shapes and sizes and various degrees of dryness. It can be as loud as the clash of cymbals or as understated as a whisper. And not only can it catch a reader unawares, it absolutely must. Humor seems just to happen; worse yet, it happens to some, but not to others. A passage that has one reader in stitches goes down with another like a lead balloon. I open my introduction to Sentimental Tales with a quote from E. B. White. Humor, he writes, “has a certain fragility, an evasiveness, which one had best respect.” Laugh to your heart’s content, but be warned: “it won’t stand much poking.” Pity us translators, whose job it is to poke!

And yet, from time to time, our pokery produces results that satisfy—if not everyone, then at least ourselves. I’ll offer an example. In the first of Zoshchenko’s sentimental tales, titled “Apollo and Tamara,” our sublimely inept but earnest narrator, I.V. Kolenkorov, spills a lot of ink on the admirable physical attributes of his titular hero, Apollo Semyonovich Perepenchuk. Working his way down from the man’s “lower lip, perennially bitten in pride,” he lingers on the throat: “Even his Adam’s apple, his plain old Adam’s apple—or, as it’s sometimes called, the laryngeal prominence—which, when glimpsed on other men, is apt to trigger disgust or laughter, looked noble on Apollo Perepenchuk, whose head was invariably thrown proudly back. There was something Greek about that prominence.”

The central joke here (pity us, the explainers of jokes!) is that Kolenkorov, having used one name for a feature of Apollo’s anatomy, the Adam’s apple, needlessly offers another. This profligacy is typical of his style. As I write in my introduction, the fellow “has never met an adjective or adverb he didn’t want to introduce to another.” He is, to put it simply, a bad writer, constantly tripping over himself; he aims for profundity but comes up short, attempts to scale Parnassus and lands on his face. I hope the passage above brings across that comic effect. In any case, it took some poking.

“He is, to put it simply, a bad writer, constantly tripping over himself; he aims for profundity but comes up short, attempts to scale Parnassus and lands on his face.”

In the Russian original, the word I rendered as “Adam’s apple” is “kadyk,” the common term for the manly projection. Kolenkorov follows it up with a synonym, “adamovo iabloko” (literally, “Adam’s apple”), which is only slightly less common. Here, the translator hits a bump in the road: English simply doesn’t have two common terms for the object in question. In search of a solution, I asked myself what an English-speaking Kolenkorov would do… As usual, our struggling author is eager to impress the reader with his intelligence, with the richness of his vocabulary. Why wouldn’t he crack open a dictionary, or Gray’s Anatomy, and find a highfalutin scientific synonym for the all-too-plain Adam’s apple? After all, the whole purpose of the passage is to dignify the godlike Apollo, to elevate him, to point up his prominence, as it were. In fact, to my ear, “laryngeal prominence” is a real find in translation, an objet trouvé that’s entirely in keeping with the tone of the original but adds another little dash of comic bathos. The passage’s final sentence, “There was something Greek about that prominence,” calls to mind the Acropolis and the Parthenon, which the ill-fated Apollo Perepenchuk was never meant to see…

The personal tragedy of Apollo Perepenchuk brings us back to the book’s importance, to the question of why anyone would even bother trying to rebuild Zoshchenko’s gags in English. The answer lies in the fact that the gags are only a part—an inseparable part, but only a part—of something far more meaningful: Zoshchenko’s attempt to wrestle with eternal issues, to plumb the tragicomic depths of our existence.

“Zoshchenko knew, of course, that his stories were funny, but they were never frivolous.”

He wrote his funny stories at a seemingly inauspicious time, in the wake of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, with Stalinism already on the horizon. Bravely, Zoshchenko focused his attention not on the great collective effort of Soviet communism, but, as Kolenkorov writes in one of the four prefaces to the cycle, on “the little man, the fellow in the street, in all his ugly glory.” As he freely admits, “Against the general backdrop of grand scales and ideas, these tales of weak little people, of everyday men and women—this book about miserable, fleeting life—will indeed, one must suppose, sound to certain critics like the shrill strains of some pitiful flute, nothing but offensively sentimental tripe.” Yet it is precisely these “shrill strains” that make Zoshchenko’s book timeless, while “the general backdrop of grand scales and ideas” frays and fades.

On July 22, the 60th anniversary of Zoshchenko’s death, I wrote a post about his legacy on my blog, from which I will quote here: “Zoshchenko knew, of course, that his stories were funny, but they were never frivolous. Their humor was rooted in real life, with all its horrors. Truly great humorists are never blind to the horrors of life; they see them clearly, but transform them, for our benefit—and often at great personal cost—into a laughing matter. This makes the terrible truth bearable, not invisible. It is necessary work, for which we ought to be grateful.”

Follow Boris Dralyuk’s on his blog.