5 Classic Films that Charmed the Industry and Devastated the Environment

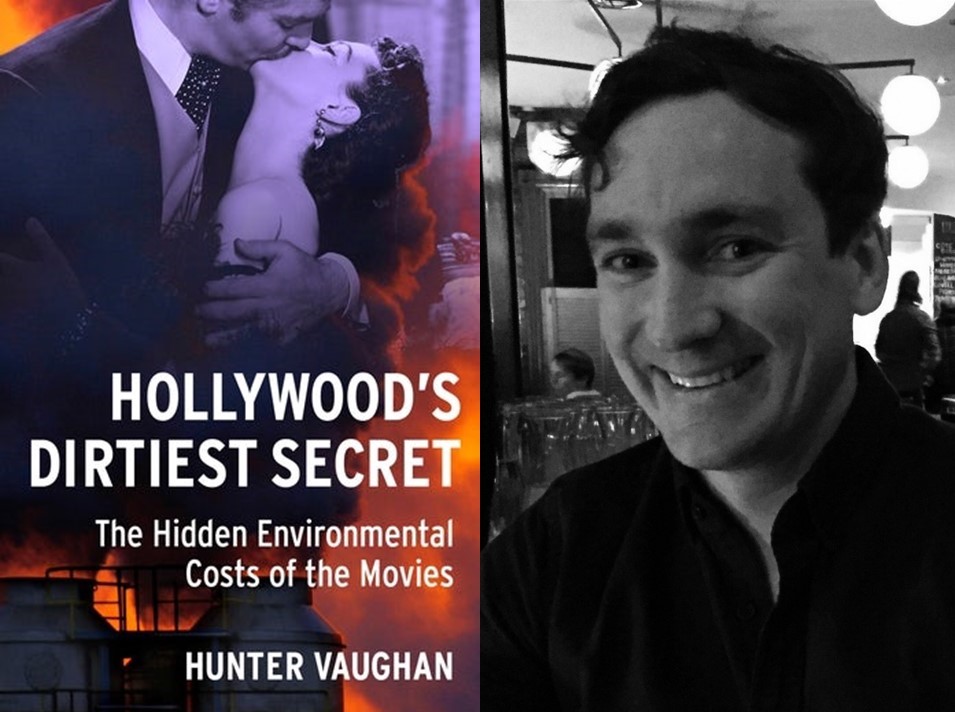

“Well-researched and written in an accessible style, it [Hollywood’s Dirtiest Secret] is a thought-provoking alternative history of Hollywood, delving into the disconnect between our enjoyment of screen culture and concern for its environmental impact. It will be of interest to scholars and students in a range of fields including cultural studies, communication, social science, and environmental studies.”

~ Alison Anderson, author of Media, Environment and the Network Society

Earlier this week, you read a guest post by and a Q&A with author Hunter Vaughan, and the introduction to his new book Hollywood’s Dirtiest Secret. Together, these posts discussed Hollywood’s gilded exterior and the jarring truth behind its fantastic cinematography, over-the-top sets, and excess use of resources that aid production and ensure box-office success. To close out the week, Vaughan turns the table on the typical cinematic award show and asks, intriguingly: if you could dole out “most environmentally unfriendly” awards to five of Hollywood’s most acclaimed films, which five would surge to the top?

• • • • • •

The bright lights and cracking sounds of cinematic spectacle have kept audiences on the edge of their seat for over a century. The magic of the silver screen casts a spell over the viewer, seducing us into a virtual fantasy that is divorced from reality not only through its fiction, but also through its concealing of the enormous material costs of its production. This valuation of entertainment over the natural resources that make it possible is indicative of our collective values, but it is increasingly clear that these values have led us, and the world around us, down the slippery slope of irreparable environmental crisis. To change our impact, we must change our values, and to do that we must address our cultural heritage: let us consider the moments of film history most indicative of our screen culture’s problematic relationship with the environment.

Hollywood’s 5 Dirtiest Secrets – and the Award Goes to. . .

5. Gone With the Wind (1939)

Hepped up on Benzedrine and an ego to outshine star Clark Gable’s, David O. Selznick’s first day of filming Gone With the Wind was one for the ages. Collecting the maximum number of Technicolor cameras available in Hollywood, the “Burning of Atlanta” sequence would set new standards for big budget spectacle of fire and destruction. A strange paradox of indulgent resource use and proto-sustainability, Selznick piped in gas to stoke the fires as the crew set aflame the sets from former productions such as King Kong and The King of Kings, an incendiary recycling program that mimicked the destruction of Sherman’s march while making room on the studio lot for the extravagant sets of Tara. Intended to wow Vivien Leigh, who was introduced to the egomaniacal producer for the first time that morning, the “Burning of Atlanta” would be central to the film’s symbolic marketing, production legend, and epic legacy of the burning of the real on the altar of silver screen spectacle. No sequence of the twentieth century had a more significant impact on the standards of film spectacle, a Hollywood legend that ignores the smog blanket above Los Angeles than the shooting contributed to, than the gas piped in to make the fire possible, and the water on hand in case the inferno got out of control. This prototype for blockbuster cinema was less the product of cinematic vision than that of natural resource use and the generation of pollution.

4. The Beach (2000)

A textbook case of environmental colonialism, director Danny Boyle’s production of a film that became the poster-child for millennial adventure tourism wreaked ecological havoc under the auspice of “raising environmental consciousness” among a local population lacking the “awareness” of Western societies. The Fox production moved into the Phi Phi Islands National Park, bulldozing Maya Bay, planting new trees, and relocating natural sand dunes in order to fit the film’s visual aims. Though producers paid off the Thai government with a donation to the Royal Forestry Department and a Tourism Authority of Thailand campaign, these financial atonements and marketing ploys did not replace the native barriers and flora when monsoon season returned, leaving the park vulnerable to the extreme weather and forces of erosion it had ecosystemically developed defenses against. A perfect example of how a Hollywood shoot acts as an invasive species, the film also generated a decade of excessive tourism that would destroy the surrounding environment.

3. Titanic (1997)

Tying All About Eve for the most Oscar nominations (14) and Ben-Hur for the most wins (11), James Cameron’s 1997 epic disaster film Titanic is a perfect case study in the ecological and environmental justice problems at once integral to our movies and completely erased from its narrative. The eternal love of Jack and Rose, which catapulted the careers of both stars and earned Cameron a directing Oscar and the first billion-dollar box office throne, garnered headlines well before it was on screen, with the ballooning budget adorning it with the false humility that marks any great Hollywood epic. From the production process to Cameron’s Oscar speech, Titanic was a model of Hollywood excess; however, the hidden environmental and local costs were severe, and never recuperated among the film’s oceanic profits. Moving from principal photography in Nova Scotia to a full-size Titanic liner built in an inlet in Rosarita, Mexico, the film’s production left an indelible footprint that has been erased from Tinseltown lore. A condensed achievement of NAFTA’s economic logic, Cameron indulged in a lavish production that, due to its employing local out-of-work local media professionals, garnered him an Order of Aztec Eagle and a photo-shoot with Mexico’s president, Ernest Zedilio. What is left out of the photo-shoot are the sea urchin population decimated by the gigantic constructed water tanks meant to stand in for the frigid Atlantic and the local Popotla fishing community permanently crippled by the production’s disturbance of surrounding ecology and wildlife.

2. Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

Perhaps no scene in the Hollywood canon better represents our culture’s valuation of entertainment spectacle over natural resources than the soundstage love confession of the Donen and Kelly backstage musical, Singin’ in the Rain. This pivotal scene in the film’s central love story provides the pinnacle of sincerity in a film that hinges on irony, artifice, and play; and, like much of the film, the white-toothed smiling innocent of its self-reflexivity seduces us into a conspiratorial trust in its revelation of the machinery of film-making. The ironic sophistication of a film like Singin’ in the Rain lures us into forgetting about Hollywood’s artifice, burying its own secrets under this sheen of honesty. However, the reality of its making is not one of magic, but of natural resources, as epitomized by the eight-day week of running water needed to perfect the downspouts and studio puddles that provided the elemental poetry of its iconic sidewalk number. During the week of preparation for this scene, the filmmakers noted a drop in water pressure when Culver City residents came home from work in the afternoon and turned on their yard sprinklers, and had to plan the shoot around this. Though this marks an implied acknowledgment that water is a finite natural resource, and part of the commons, the film’s final product is testament to the fact that Hollywood is never willing to be stumped by the limitations of nature!

1. Avatar (2009)

Self-marketed as the first fully digital feature film, Avatar reflects our emerging media landscape’s philosophical and ecological contradictions. The film’s shallow allegories for colonialism and petro-imperialism, glamorization of violence, and its un-ironic fetishization of the noble savage and uninspired heteronormativity belie the film’s real underlying message: digital effects are really cool to look at. Through his own effects studio and influential role in underwater exploration, Cameron has positioned himself as the unrivaled king of the virtual world. However, Avatar was far from fully digital, and its footprint the opposite of the myth of immateriality we have been sold by the digital revolution. Flying crew members around the world for spiritual training, building analog sets and props as the first stage of a multi-phase shooting process, and intense reliance on server support and a global circulation of information that would eventually manifest itself as the sublime distraction of Pandora, Avatar is the height of ideological contradiction: a feel-good reincarnation myth of the white male savior whose true avatar is the pseudo-environmentalist behind the camera. This irony has been lost in the oceanic swell of film culture’s machinery of legitimization (box office records, Academy Awards, coffee table books, planned sequels), but the lasting footprint of Avatar is incalculable: from the high carbon footprint of transportation to the reliance on a vast and constantly running server infrastructure, this is the new standard for blockbuster film spectacle.

2 Responses