James Davis on the History of the Blackface Performance

This week we’re celebrating Black History Month with this guest post by James Davis, author of Eric Walrond: A Life in the Harlem Renaissance and the Transatlantic Caribbean. In this post, he discusses the blackface performance.

Enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book.

• • • • • •

The blackface controversy consuming the Virginia statehouse reminds us, this Black History Month, of how pervasive this performance has been. One way of saying this is that white Americans have always been racist and have been especially slow to “evolve” in some parts of the country. Another way of saying it is that most white people were doing it “back then” – whenever then was – so blackface is not a reliable indicator of the performer’s beliefs about race. These alternative explanations are satisfying to those seeking to condemn or defend, which seem in our hashtag moment the only available options. But if the history of blackface teaches us anything, it is that this performance is both an index of white supremacist culture and yet much more. It is rarely an either-or proposition, either a derisive expression of anti-blackness (companion to the Klansman) or an innocent tribute (the moonwalk, accessorized). One challenge of studying representations of African Americans historically is that the mediating contexts are so important and so difficult to reconstruct.

“But if the history of blackface teaches us anything, it is that this performance is both an index of white supremacist culture and yet much more.”

In my biography of Eric Walrond, a Harlem Renaissance writer who immigrated from the Caribbean as that movement was gathering force, I continually ran up against the complexity of efforts to mark language as Black: to write so that non-Black readers would feel “woke” (to use today’s parlance) and also address a Black audience seeking something authentic, something that looked and sounded like they did.

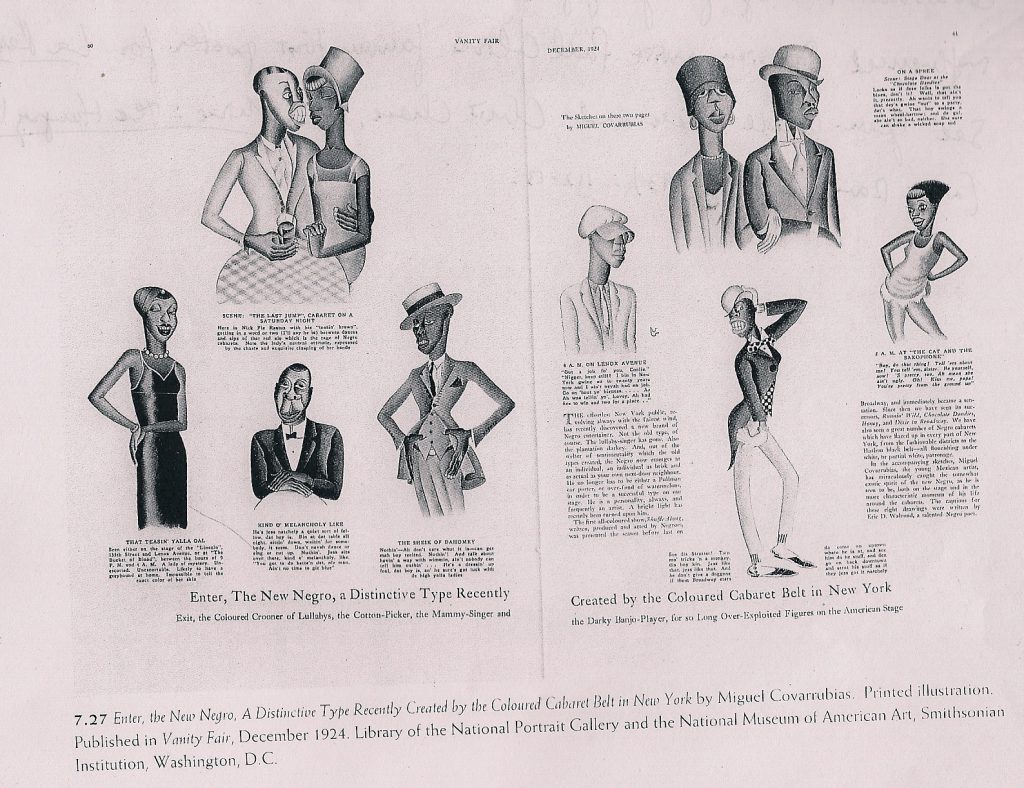

Consider a Vanity Fair project on which Eric Walrond collaborated in 1924 with the visual artist Miguel Covarrubias, himself a recent immigrant to New York from Mexico City. Walrond’s writing career was not yet anointed by the publication of his first book, Tropic Death, but his collaboration with Covarrubias registered the intensity of his interest in what was called Negro dialect. A two-page visual spread, it was titled, “Enter, the New Negro, a Distinctive Type Recently Created by the Colored Cabaret Belt in New York.” As I note in the biography, the Covarrubias images verge on caricature, stock figures given a Jazz Age makeover, adorned with exaggerated lips, distended smiles, and ostentatious garb. Each image was accompanied by a clever caption by Walrond, beginning with a suggestive title, a bit of Harlem slang.

“To today’s viewer, the objectionable elements are clear despite the gorgeous line of Covarrubias’ drawing and the rhythm of Walrond’s prose.”

The project highlighted an important dimension of the New York cabaret scene, the blurred line between spectator and performer. To today’s viewer, the objectionable elements are clear despite the gorgeous line of Covarrubias’ drawing and the rhythm of Walrond’s prose. To the editor of Vanity Fair, however, the figures were a kind of triumph over insulting images of blackface minstrelsy. They suggested something new, he wrote, closer to authentic Blackness. “Exit, the Coloured Crooner of Lullabys, the Cotton-Picker, the Mammy-Singer and the Darky Banjo-Player, for so Long Over-Exploited Figures on the American Stage,” he explained. “Out of the welter of sentimentality which the old types created, the Negro now emerges as an individual, an individual as brisk and as actual as your own next-door neighbor. He no longer has to be either a Pullman car porter, or over-fond of watermelons, in order to be a successful type on our stage. He is a personality, always, and frequently an artist.” The stereotype was supplanted by the individual, the distorted image replaced by the actual, sentiment subdued at last by reality. But, any viewer today would query the assertion and note the will to be hip and “woke,” the eagerness to displace blackface by images that were morally commendable but were no less stylized.

“To the editor of Vanity Fair, however, the figures were a kind of triumph over insulting images of blackface minstrelsy. They suggested something new, he wrote, closer to authentic Blackness.”

The controversy consuming the Virginia statehouse has occasioned a long overdue debate about the relationship between blackface performance and state power. But the terms of debate reiterate a familiar dynamic, in which normative liberal anti-racism is asserted to purge the field of bad old ideas and misrepresentations. One wonders whether each American generation since Harriet Beecher Stowe has engaged in this ritual, only to discover, upon confrontation by the next generation, that the underlying structures of feeling and racialization remain intact.