Onno Oerlemans on Poetry and Animals

“Onno Oerlemans’s Poetry and Animals represents an important contribution to the scholarship on animals and human-animal relations in literature. We badly need some excellent work on poetry from a human-animal studies perspective, and this book provides a provocative, erudite, thoughtful, and engaging contribution.”

~ Philip Armstrong, author of What Animals Mean in the Fiction of Modernity

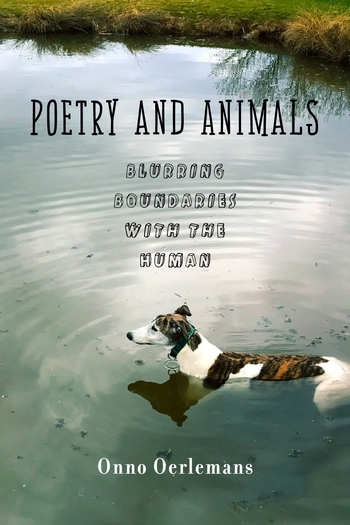

We’re kicking off the month of February with a Q&A that our literary and poetry readers will like. We recently published, Poetry and Animals: Blurring the Boundaries with the Human, by Onno Oerlemans. In this post, Oerlemans walks us through his initial interest on the subject, the motivation behind writing the book, and about the cover.

Remember to enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of this book!

• • • • • •

Q: When did you first start to dedicate time towards analyzing the role of animals in poetry? What started your thought process? In other words, what first inspired you to study, write about, and teach the topic of animals in poetry?

Onno Oerleman: I began my scholarly career studying Romanticism and literary theory, having done my PhD at Yale in the 80s, where deconstruction and New Historicism were predominant modes. Once I started teaching, though, first at the University of Ottawa and then at Hamilton College, while I didn’t exactly abandon theory, I was hungry for new ways of making literary criticism relevant, both for myself and my students. I had always been interested in animals and the natural world, having had what amounts to a deeply Wordsworthian childhood growing up in the wilderness of Northern Manitoba. In The Prelude, Wordsworth writes about the thrill of hooting at owls; I howled with wolves, and the sheer joy and excitement of those moments, has always stayed with me, anchoring my sense of why the natural world matters. So the turn to ecocriticism generally, and animal studies more specifically, was completely natural (!) for me. It struck me as increasingly obvious that the “one life within us and abroad,” as Coleridge put it, or Wordsworth’s “spirit … that rolls through all things,” the consciousness that is not (only) human, but is out there in the natural world, actually exists in animal life. Romantic poets actually wrote many poems about animals, and you can see glimmers of this awareness–that animals are conscious, sentient beings who can help us feel connected to the natural world—in many of these poems. So that was the scholarly beginning of my turn to animals. But I have always been interested in animals, and of course virtually everyone is interested in animals. Bring a dog to class. Bring a dog anywhere, and she is the immediate object of everyone’s attention. This interest is nearly universal, and it’s profound.

Q: When did you first have the idea to make this topic into a book? Had you already recorded your analysis, or did you write these chapters with the intention of creating a book like Poetry in Animals? Take us through your process!

OO: There were several sources for the motivation behind the book. I had done some research on animals in Romantic period poetry for my earlier book, though I was more interested in the various ways that the actual physical world mattered to the poets of the period. More concretely, though, I’d also noticed in my teaching that any poem on animals produced immediate and excited responses in students, especially when I asked them to think not just about what the poet or poem was doing with the animal, but about the actual animal that the poem was in some way representing or using. I wanted to write a book for my students, really, and inspired by them. I’m kind of a generalist in my teaching, and I’d also noticed that animals occur in poetry from every era, in every nation and culture that I’d studied. As I say in the book, there are thousands of poems about animals, including many deeply canonical ones (“Ode to a Nightingale,” “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking”!). But most of these poems have been studied only in the context of the individual authors or periods, and they almost always begin with the assumption that the animal is symbolic, that it stands for something human, which makes the actual animal uninteresting or beyond knowing. But this seemed to me wrong; poets, like the rest of us, are also genuinely interested in the animals themselves, in trying to know something about them, in seeing and studying them. Another motivation for deciding to write this book came in noticing that while new work in critical animal studies had focused on the work of narrative, images, and film, there was virtually nothing on poetry, aside from scattered work on individual writers or poems. I wanted to do something big and broad, breaking out of the usual categories of focus for literary criticism. The first step was simply to gather and read as many poems as I could find about animals. I asked friends and colleagues, and hired a brilliant undergraduate to help me find and collect these poems. I took notes on at least a thousand poems, and I know that there are many thousands more out there. In doing this, I became even more convinced that poetry is useful for thinking about and developing our understanding of animals, and that animals have, as I say, been endlessly interesting to poets.

Q: Many people often say that a writer doesn’t create meaning; readers do. Is this something you agree with? Why, or why not?

OO: Of course it has to be both, and more. A poet produces meaning immersed in language (which is socially constructed), and within many literary and cultural traditions. She then creates a poem filled with her own intentions to create meaning, and good poets are fully aware that there are many possible meanings that they are engaging with whose implications/meanings they are not fully aware of. Readers of poetry bring their own contexts and experiences, and good readers are as open as possible to the diversity of possible meaning.

An interesting critical insight for me in thinking about animal poems is how many readers (critics and students alike) initially refuse to see poems about animals as actually about animals. Many readers assume that because poetry is “serious” and “profound” it must always be about something deeply human, or deeply personal for the poet. And these assumptions almost always exclude the animal as a possible subject of the poem. This is one of the biases or reading practices I hope to disrupt with my book, to allow readers to think about poems about animals as actually about animals, that this is an interpretive choice they can and probably should make. On the other hand, some poems can develop personal meanings and relevance that might not be accessible to others. For instance, I give an explicitly personal interpretation of Wordsworth’s “A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal” in the book, in which I read it as about the death of a pet. The poem is itself rather cryptic, because it’s not at all clear whom (or what) the speaker of the poem is referring to as having died. I remember that when I first taught the poem the experience it reminded me of was my first encounter vivid encounter with death, when the family dog died as we watched, which utterly shocked me even as I knew it was coming. Seeing a body die is to be reminded that we are all animals.

Q: What’s your favorite animal poem?

OO: There are so many wonderful ones! That’s another reason I wrote the book, and of course I developed new passions for poems as I wrote the book. Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Moose” is one of the poems that inspired me to write the book, and has stayed with me for a long time–even though the animal isn’t actually the central topic of the poem (which is instead about a young girl’s transnational bus trip). The poem ends with the bus stopping for a moose on the road; everyone on the bus is taken out of their isolation to stare at the “grand, otherworldly” creature, and the narrator wonders “why do we feel/ (we all feel) this sweet/ sensation of joy?” This moment of the poem, its climax, has stayed with me from the beginning to the end of the process of writing the book: the knowledge that encounters with animals can somehow produce a mysterious and healing joy when we regard them as of the world, their own beings, rather than just creatures we’ve produced for our own purposes. I also found the poem a kind of allegory about approaching animals. It can take a while to see animals in and of themselves, and it can be accidental, a sudden revelation. (Some people argue that we can never see or represent animals as they are, echoing Thomas Nagel’s famous argument about bats. But I take this view as dogmatic and ethically absurd. More or less the same can be said about knowing other people, and we do of course have the ability to imagine, which, as Shelley said, is the key to moral understanding.) James Wright’s “The Blessing” is more singularly about this deeply healing (even selfishly so) effect of connecting with an animal, and it’s a poem that still brings me to tears. Blake’s poem “The Lamb” is also a fantastic and hugely instructive poem. It is about taking animals seriously, talking to them, which requires both a wonderful innocence and taking an imaginative leap. The poem is about a child’s seemingly natural and spontaneous ability to talk to animals as near equals, an ability and desire we lose or suppress (out of embarrassment) as we get older. And yet, I’ve never had anyone in a class deny that they too have spoken directly to an animal (usually a pet) as though the pet could understand. Poetry can remind us of that hope, that directness, that potential for reaching out.

Q: Finally, the cover of your book is very engaging. Can you tell us about the cover image?

OO: The photo was taken with my phone, believe it or not, and is of one of my dogs. I joke that this is a book that should be judged by its cover because it’s such a striking photo of such a beautiful animal. The dog is my greyhound Beloki, who was a rescued racing dog, whom we named after a retired professional cyclist (and both stopped racing after shattering their legs in racing accidents.) He had a heart of gold; he loved meeting people, being loved by them. I used to joke that his goal in life was to let people love him, to share his happiness with everyone. He became a fantastic therapy dog, since he was both gorgeous and utterly magnetic and so enjoyed hanging out with people. (That contact with animals can be therapeutic, can make us feel and be better, is one of the basic truths behind why there are so many great poems about animals!) Beloki also loved to cool off in various ponds, lakes, and ditches, entering a state of seemingly Zen-like calmness when doing so. I often took photos of him in water, in part because he looked so utterly content, and looking at him made me happier too. This photo stood out to me because of the ripples of water surrounding him, caused by his breathing or heartbeat. He made the whole pond come alive. He’s also staring away and half-hidden, which seems to me symbolic of how poetry approaches the animal—generally by knowing that there’s more we can’t know than we can. He was a gorgeous, confident, outgoing dog. I felt special just by standing next to him somehow, and this picture–and the book–now memorialize him. He died very quickly and quite unexpectedly of cancer just a few weeks after the book came out.