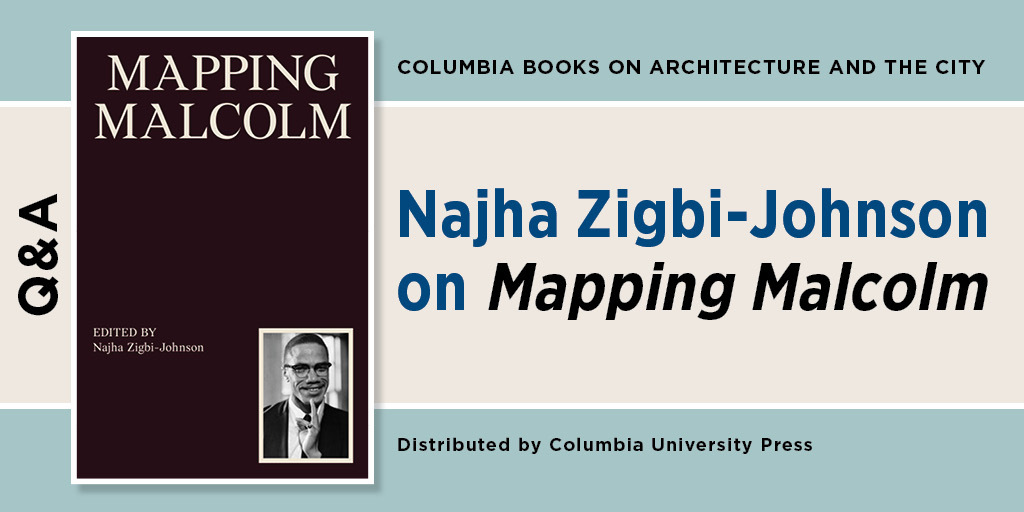

Q&A: Najha Zigbi-Johnson on Mapping Malcolm

Mapping Malcolm is a collection of essays, conversations, and works of art that reinscribes Malcolm X’s memory and legacy across the built environment, forms of contemporary community building, and Black freedom movements as they continue to manifest across New York City and beyond. In this Q&A, editor Najha Zigbi-Johnson provides insight into the work of the book and discusses her reasons for centering Malcolm X as a teacher and guide.

Q: Najha, your book rallies over a dozen scholars, artists, and activists around a core commitment to Black social justice, spirituality, and solidarity as manifested through Malcolm X. Tell us, why Malcolm?

Najha Zigbi-Johnson: For as long as I can remember, I have loved and admired Malcolm X, even before I could fully begin to articulate his religious, political, or cultural vision. After completing graduate school in the spring of 2020, right as the Covid-19 pandemic-turned-racial-reckoning took hold of the United States, I became particularly committed to the work of institution building. Like many of my peers, I was preoccupied with the need to reimagine and rethink Black institutions as sites for expansive liberatory opportunities, creative expression, and community development. During that particularly fraught and uncertain time, I was also watching the documentary series Who Killed Malcolm X? and was reading through the new Garrett Felber book, Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State. I remember being so engrossed at one point in the series and history that I ended up missing a call inviting me to apply for a position at the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center (the Shabazz Center). I share this anecdote because I truly believe the Ancestors guided me to Malcolm and his legacy.

While working at the Shabazz Center, I became deeply interested in the how younger generations, and particularly Black and Brown folks, could continue to make sense of both the movement for Black lives and its political lineage, which can be traced to Malcolm X’s work with the Nation of Islam and, later, the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Through my time spent learning and working at the Shabazz Center, I began to see the many ways in which place-based history, preservation, and the larger legacy of Harlem has been informed by Malcolm’s life and revolutionary practice. While there are a range of political figures who continue to shape our global solidarity movements, Malcolm X has become an entry point and springboard to a range of praxis-oriented questions and histories that together center Harlem as an active site of history, cultural production, and resistance against gentrification and imperial expansion.

Q: And also, why “mapping”? We can’t help but notice there are no “maps,” at least in the traditional sense, in the book.

Zigbi-Johnson: Right. In a sense, offering up a literal map of Harlem, even Malcolm X’s Harlem, would have been too easy. Rather, this book project has attempted to show how Malcolm’s life is itself embodied by the built environment. Through art, music, archives, conversation, food, poetry, and essays—academic and not—Mapping Malcolm seeks to resurface the ways in which Black spatial forms are the byproduct of Black culture and politics. Mabel O. Wilson, an architect and designer and the director of the Institute for Research in African American Studies at Columbia University, posits “Black counter cartographies” as a way to explore how the spatial practices of Black life might in turn construct new ways of mapping “sociality, imagination, and liberation.”[1] Mapping Malcolm looks to the scholarship of Wilson and other Black scholars who are reimagining the ways in which space is produced through various social and environmental forces. In this sense, we learn about the history of Harlem through the political and cultural moments that shaped Malcolm X and, by extension, this neighborhood.

Q: What do you hope architects—or anyone interested in the built environment—learn from this book? What can Malcolm X teach and offer the discipline of architecture, specifically?

Zigbi-Johnson: Malcolm X’s analysis of power remains critical of the relationships established between institutions and people. Malcolm was in many ways an ethical steward and moral exemplar of how to engage structural and interpersonal power in ways that could benefit even the most marginalized peoples. His political vision and worldview should increasingly inform architects, planners, preservationists—all world-makers who are quite literally structuring the built environment. Malcolm encourages us to situate Black liberation, community stewardship, and transnational solidarity both as a praxis-centered approach to space making and as a transdisciplinary pedagogy that may help us think through the decades of racist practices that have shaped the development (or lack thereof) of communities across the United States and, most saliently, Harlem.

Harlem, for that matter, is a major protagonist in the book. This is the place where I live and work; where we are still contesting the terms of property, gentrification, and imperial/institutional expansion; where radical forms of freedom-seeking and freedom-building movements have and continue to unfold.

I also remain in constant awe of the sheer number of spaces and ways that Malcolm X is memorialized throughout Harlem. Before starting this book project, I thought a lot about Lenox Avenue/Malcolm X Boulevard and Temple No. 7 on 127th Street, founded by Malcolm. I thought a lot about the Nation of Islam members who sell bean pies and copies of the Final Call newspaper. But I hadn’t quite realized how ubiquitous Malcolm X truly is to Harlem—how his memory is maintained through formal and informal ecosystems throughout the neighborhood.

Q: There is a variety of artistic and archival research featured throughout Mapping Malcolm. How are these various mediums working together across the book?

Zigbi-Johnson: As a project, Mapping Malcolm is especially interested in what people across disciplines and mediums have to say about Malcolm X, and how we make sense of his legacy and world-making processes. The scholarly essays within this project offer a new and expanded material, religious, and political perspective on Malcolm X that places him within a global context. But I firmly believe that visual and sonic art best reflect the possibilities of freedom and wholeness alongside the simultaneous pain and trauma that mark the human experience. In order to feel Malcolm’s vision, and not just theoretically explore his worlds, I became interested in including a range of visual aesthetics that nod to the Black radical tradition, while incorporating elements of futurity since, ultimately, Malcolm was fighting for a future where Black people could exist. In addition to commissioned and republished art, Mapping Malcolm features a range of historical and archival imagery that centers Malcolm X’s transnational relationships, alongside his humanity and capacity for joy as the central emotional element. In highlighting these images, we have chosen to celebrate a side of Malcolm that is often overlooked in the popular mischaracterization of his persona and politics as extreme and anger-filled.

Q: How does this book differ from other books on Malcolm X?

Zigbi-Johnson: This book is unique in a lot of ways. I think about my particular social location and positioning as a millennial Black woman writing, researching, and exploring a historical figure. I may be one of the youngest women to publish a collection on Malcolm X. So, in this way, the book is a decidedly intergenerational project that seeks to connect the historic roots of the Black power movement to the political and cultural world of younger generations, who have come of age in a post-Obama world and understand internationalism, anti-imperialism, and race through a very different lens and context than our predecessors.

Also, importantly, this book is not a biography on the life of Malcolm X. Rather, it is a reflection of the ways in which Malcolm X’s political, religious, and cultural legacy has shaped generations of scholars, organizers, and artists who are building within the Black radical tradition. Mapping Malcolm exists beyond any one genre: it speaks to a range of people and interests, from design and urban history to photography and Black radical politics. The book will hopefully interest a wide variety of people, including folks who may not have traditionally explored this dynamic legacy.