George Kallander on Na Man’gap’s The Diary of 1636

“The Diary of 1636 is a fascinating firsthand description of the turmoil and difficulties in Chosŏn Korea during the second Manchu invasion. George Kallander’s engaging and highly readable translation provides an understanding of the Chosŏn response to the invasions, internal power struggles, and consequences of this momentous event that reshaped the face of East Asia.”

~Michael J. Pettid, coeditor of Premodern Korean Literary Prose

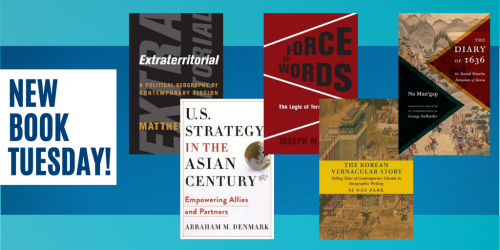

We continue our celebration of National Translation Month with a look at a singular document from Korean history: Na Man’gap’s Diary of 1636: The Second Machu Invasion of Korea. Na was a Korean scholar-official whose journal provides the only eyewitness account of the second Manchu invasion of Chosŏn Korea. In this blog post, translator George Kallander situates the diary in its historical context and considers the ways it resonates beyond that context as a story of personal survival, one that engages with multiple storytelling strategies and perspectives, connecting this seventeenth-century work to the present.

Check out our National Translation Month overview for a chance to win a copy of this book and to read and excerpt.

• • • • • •

In the winter of 1636–1637, 140,000 Manchu and Mongol soldiers crossed the frozen Yalu River and invaded Korea. The Diary of 1636, by Na Man’gap, is a record of the attack, resistance, and political fallout of this invasion. Na was a scholar-official at the Chosŏn court who retreated to a mountain fortress outside of Seoul with the Korean king, officials, and soldiers. From there, they defended the fortress from the assailing armies.

The Manchu Qing was a rising power in northeast Asia. Before challenging the Ming dynasty for control of the Chinese heartland, the Manchu emperor demanded Korea’s pacification. The Manchu first invaded Korea in 1627, forcing Korea to end an alliance with the Ming. However, once the Manchu armies retreated, the Korean king severed relations with the Manchu and allied again with the Ming, a move that enflamed the Manchu and threatened war a second time. The Korean leadership was split over how to respond. Some wanted peace with the Manchu while others wanted war. Many viewed the Manchu through a rigid Confucian lens, arguing that the Manchu could not be trusted because they were not part of the civilized Chinese sphere of influence. Na observed, even in the face of an overwhelming Manchu threat, that the Korean king “strove to convey his hatred of the enemy” as the elite of the country submitted petitions “from near and far. . . . Every one of them called for war and attacking the barbarians.”

“The Manchu armies were well seasoned and numerous. They captured royal family members and began starving the defenders out of their mountain fortress.”

Na narrates a number of small Korean victories. In one battle, he writes, “The officer whispered that the enemy was entering the fortress . . . The soldiers first tried to throw large rocks. After that, they used metal ingots and then fired arms at the enemy. The enemy fell in large numbers and finally retreated . . . The next day at first light, we could see the enemy dragging their dead companions away. The blood glowed red in the snow and ice.” Despite these moments, the Korean king eventually surrendered. The Manchu armies were well seasoned and numerous. They captured royal family members and began starving the defenders out of their mountain fortress. Rather than victimhood, however, Na’s account demonstrates Korean agency and resilience. Korean dynasties actively engaged with some of the most powerful empires and militaries in world history (such as the Mongol Yuan, the Chinese Ming, the Manchu Qing, and the Japanese), negotiated those relationships, and always survived.

The Diary of 1636 suggests the dangers of following policies based on rigid political ideologies. For much of the Korean leadership, total Confucian reverence for the Ming brought immense suffering to the country. Even when faced with defeat, many in the leadership wanted to continue their alliance with the Ming. Na confesses to the king that he and other officials “were ready to die to defend the fortress” rather than give in to the Manchu. When the king surrendered, a number of officials committed suicide. Some men even forced their wives and daughters to kill themselves. Na recounts: “There were countless numbers of women who died to maintain their chastity. It is regretful that all of them cannot be known.” Shifting allegiance from the Ming to the Qing was traumatic for Korea. The Chinese had helped defend the country against a massive Japanese invasion at the end of the sixteenth century. Tens of thousands of Chinese had died defending Korea, a sacrifice not easily forgotten, and Confucianism demanded loyalty to the Ming despite the Ming dynasty’s decline. Alternative voices in Korea that understood the military power of the Manchu called for peace, but louder “patriotic” calls of resistance silenced them.

“Composed in the seventeenth century, the diary is meaningful to contemporary readers as its themes transcend time and place.”

Composed in the seventeenth century, the diary is meaningful to contemporary readers as its themes transcend time and place. Through a wide lens, it is a story of national survival. Na describes how Korea anticipated the Manchu attack but was still unprepared. Leaders ignored warning signs and continued policies that threatened the country. Despite having years to prepare, the king and court failed to establish national defenses or negotiate terms with the Manchu before the invasion. Faced with clear choices during the invasion, court officials squabbled over decisions that only prolonged the suffering of the people. In the end, the king, in surrendering to the Manchu, ended support for the Ming and recognized the Qing as superior. This shift, described in the diary, unleashed bitter factionalism where different parties denigrated their rivals to advance their own causes, fueling a toxic political environment.

At the most basic level, the diary is a story of personal hardship and survival. Na Man’gap wrote the first half in the besieged mountain fortress much like a day-by-day blog of his experiences. These daily accounts range from seemingly mundane observations of the weather to long descriptions of military campaigns and political debates with the king and other officials, all while he and his comrades faced constant danger from attacks and food shortages. The second half of the diary moves in and out of the past and present to retell the events from multiple perspectives in an interestingly postmodern-like blend of storytelling genres that is surprising for a work from the first half of the seventeenth century. The reader pieces together the bigger picture through myriad frames of reference and forms of writings—petitions, rumors, poetry, state letters from Korea and the Qing, and firsthand and secondhand reports of Koreans, Manchu, and Chinese soldiers and officials. By the end of the diary, we sympathize with Na and those who experienced the hardship of war while also recognizing the similarities between the seventeenth-century world and our own.

We encourage our readers to support independent bookstores. Bookshop.org makes it easy to order from bookstores across the nation and this map can help you find a bookstore near you. Visit LitHub for a curated list of black-owned bookstores.