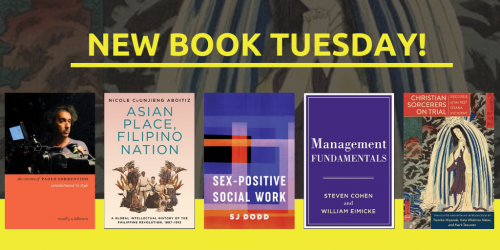

The Unprecedented 1827 Osaka Incident

By Kate Wildman Nakai, Mark Teeuwen, and Fumiko Miyazaki

“Christian Sorcerers on Trial is a model of consummate scholarship and at the same time a gripping narrative which will be of great interest not just to students of Japanese religion and history, but to anyone curious about Japan in the decades immediately before its so-called ‘opening up’ by the West.”

~John Butler, Asian Review of Books

We continue our celebration of National Translation Month today with a look at a fascinating book, Christian Sorcerers on Trial: Records of the 1827 Osaka Incident, recently translated by Kate Wildman Nakai, Mark Teeuwen, and Fumiko Miyazaki. In this guest post, the translators discuss what reading these extraordinarily rich testimonies from the women and men tried and executed for belonging to the “Kirishitan” sect – as well as attending to the legal deliberations, rumors, and retellings tied to this event – reveals about daily life, law, and religious practices in the late Edo period.

Check out our National Translation Month overview for a chance to win a copy of this book and to read and excerpt.

• • • • • •

The word “unprecedented” reverberates through the materials translated in Christian Sorcerers on Trial: Records of the 1827 Osaka Incident. Summing up the investigation he had overseen, the Osaka magistrate wrote, “Never before has there been an investigation in this city of perpetrators of these kinds of evil acts.” The “evil acts” of which the accused were held guilty were the practice of the “pernicious creed,” Christianity. As noted in a blog post in 2019 that previewed this book, Christianity had been strictly proscribed in Japan since the early seventeenth century, and it had been well over one hundred years since the last groups of Christians—or Kirishitan, as they were called—had been exposed and executed. Officials subsequently had taken a more restrained approach. In the decades immediately before the Osaka incident there had been investigations of irregular practices among villagers in Kyushu, whom researchers today assume to have been “underground Christians,” descendants of converts of earlier centuries. But in those instances the officials had sidestepped the possibility that the people investigated might be Kirishitan. They thereby also avoided taking draconian measures that would have affected large numbers of villagers and might have caused social unrest.

Not only was the discovery in the 1820s of a group of Kirishitan in the Osaka area thus something unprecedented, so was the assertive approach taken by the investigating officials. The case presents other distinctive dimensions as well. The Osaka Kirishitan seem to have had no connection with the Kyushu underground Christians, who have received much greater attention from researchers, and their practice was very different, too. By background they belonged to the underclass that by the nineteenth century made up a significant part of the urban population—individuals who had drifted into the cities from elsewhere and eked out a livelihood through miscellaneous unstable occupations. Several of the principals were mediums and healers, and they combined elements of Christian origin with methods of ascetic training common to a wide range of popular religionists. They also took a positive view of what the officials saw as a prime evil of the Kirishitan creed, its presumed association with sorcery. The accused saw the powers of sorcery attributed to Kirishitan as something that could enhance their skills as diviners and bring them wealth and fame. The testimonies that detail how the principals came to encounter the “pernicious creed” and the nature of their practice thus shed new light on the complex legacy of Christianity in early modern Japan.

“Several of the principals were mediums and healers, and they combined elements of Christian origin with methods of ascetic training common to a wide range of popular religionists.”

Another striking feature of the Osaka incident was the prominent role played in it by women. Of the six principals ultimately executed, three were women. On the assumption that women by nature were weak and passive, the judicial system of the time tended to view women accused of wrongdoing as accomplices rather than the main perpetrator and to deal with them less stringently than men held guilty of the same crime. In this instance, though, the women were seen as—and indeed were—the more active parties. As the officials put it in summing up the testimony of each of the three female principals, “Showing not the slightest awe for the shogunal authorities,” they had “acted in a manner that was the height of audacity for a woman.” The women, for their part, accepted the charge. Widowed or abandoned by their husbands, they had chosen to make a living as mediums rather than remarry, and they took pride in abstaining from sexual relations and in the arduous ascetic training that had enabled them to obtain the “unwavering mind” necessary for initiation into worship of the Kirishitan Lord of Heaven. Their rejoinder to the officials was that “lustful and greedy people would never be able to do the things” they had.

“Of the six principals ultimately executed, three were women.”

Scholars such as Carlo Ginzburg and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie have shown the capacity of European Inquisition records to illuminate the mentality and lives of otherwise little-known people of earlier ages. Compared to the Inquisition officials, the Osaka investigators were much less interested in the souls and, thus, the minds and ideas of those they interrogated. Their concern lay rather with practices and activities, which the testimonies they took down document in fascinating detail. And just as with the Inquisition records, the testimonies coincidentally afford a view into the daily lives of individuals of a sort that rarely make this distinct an appearance in the pages of premodern historical sources—not only the principals but also the family members, associates, and acquaintances who likewise became caught up in the investigation. Accounts of the deliberations on the case at higher levels of government, which the book includes as well, similarly open a window onto the operation of the early modern Japanese judicial process, and translations of rumors about and retellings of the incident show how it was received by people of the time and later.

Materials such as these relate extraordinary events specific to a particular place and time. Equally, however, just like works of literature or reportage, they tell a story of the human condition that is of universal interest. Their translation will, we hope, make that story widely accessible.

We encourage our readers to support independent bookstores. Bookshop.org makes it easy to order from bookstores across the nation and this map can help you find a bookstore near you. Visit LitHub for a curated list of black-owned bookstores.