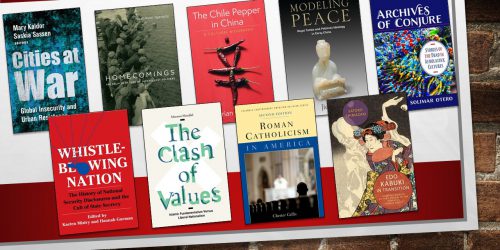

Yemayá, Water Logics, and Archives of Conjure in Afrolatinx Cultures

By Solimar Otero

“A poetic, fluid, and compelling book. By producing an ‘archive of conjure’ pieced together through interwoven elements of ethnography, literature, archival notations, bolero music, poetry, and other Afrolatinx inspirations, Solimar Otero provides humanities scholarship with a new, transdisciplinary technique and approach. This is a powerful intervention and must read!”

~Aisha M. Beliso-De Jesús, author of Electric Santería: Racial and Sexual Assemblages of Transnational Religio

Solimar Otero, author of Archives of Conjure: Stories of the Dead in Afrolatinx Cultures, draws on her work to discuss Afrolatinx religious practices, such as Cuban Espiritismo, Puerto Rican Santería, and Brazilian Candomblé in today’s guest post. Learn how they can be understood through the histories of water and aquatic gods.

• • • • • •

On December 1, 2016, an international group of Ifa priests known as babalawos gathered at the Cuban Yoruba Cultural Association in Havana to divine la letra del año, the coming year’s divinatory sign. This sign indicates reigning gods, global events, personal challenges, and important ritual and symbolic work to be done. The sign for 2017 was Baba Egiobe, and the deities of war, Ogún, and the ocean, Yemayá, would rule the year’s events. I spoke one afternoon on the phone to Alex Fernández, a Santería elder based in Miami, and about the year’s sign, he simply stated, “Yemayá está revuelta con la humanidad [Yemayá is worked up about humanity].”

I interpreted this to mean that Yemayá is pissed off, and with good reason. This maternal, feminist deity is the patron of LGBTQ communities, a steward of the environment (especially the sea), and a disobedient wife to the war deity, Ogún, who also marked this year. Tidal waves of violence, devastation, and distrust ravaged so many in 2017 that the feelings of overwhelming fear, anxiety, and helplessness have become common denominators uniting many of us. This is even more the case now as we face the corona virus pandemic in 2020.

“I interpreted this to mean that Yemayá is pissed off, and with good reason. This maternal, feminist deity is the patron of LGBTQ communities, a steward of the environment (especially the sea), and a disobedient wife to the war deity, Ogún, who also marked this year.”

By engaging in empowering rituals like la letra del año, Afrolatinx religious communities confront social, political, and environmental violence. My book, Archives of Conjure: Stories of the Dead in Afrolatinx Cultures engages with the logic of Yemayá’s anger as a means of reading Afrolatinx rituals, histories, and cultures. There is a logic to water-work that operates in an amorphous collectivity that sparks the human imagination and begs connections to life-forms and ecologies larger than and different from our own. In Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería, the ocean is a site where the dead reside and do important work on behalf of the living. Deep-sea deities like Agwe and Olókùn preside over the mysteries that the dead encounter upon reaching their watery realms. This book uncovers the ways the dead speak to us about the past, present, and future through practices like séances, archival work, and storytelling. Yemayá, as the mother of all beings and the queen of all water, serves as an important guide to reading these messages from the dead through clues left as residual transcriptions. These transcriptions can be coded in beads and dolls made by practitioners of Afrolatinx religions or appear as jotted notes recalling a prescribed ritual.

The cyclical nature of aquatic currents is at the heart of my book’s organization. The deities Yemayá, Ochún, and Erinle; guardian spirits; and mermaids are important guides to how residual transcripts become archives of conjure. Each chapter operates as a séance that invites water entities and scholarly ancestors to the mesa, or spiritualist table, for conversation and work. The flow of topics in each chapter has attending dead, deities, and scholarly ancestors at the center of their connections. There are flows within flows in the topics addressed, like the relationship of water to Afrolatinx history through slavery and migration, that are situated like counter-currents with their own routes of reading.

“The undertow is a metaphor that recognizes the significant role that women and LGBTQ+ communities play in Afrolatinx religious histories and experiences.”

The undertow is a metaphor that recognizes the significant role that women and LGBTQ+ communities play in Afrolatinx religious histories and experiences. Like undertows and counter-currents, their stories and spiritual lives flow vitally away and against patriarchal, homophobic, racist, and colonial interpretations of practices. Often unnoticeable to the naked eye and working beneath the surface, the contributions of women and LGBTQ+ practitioners of Afrolatinx religions are recorded in the residual transcriptions of the dead because of the nourishment they provide to one another. In Archives of Conjure, the religious histories revealed by the dead, scholars, and orichas (deities) assert the centrality of groups and individuals often marginalized by the traditional study of world religions. The flow of the undertow in the book invites readers to consider how unseen yet felt collaborations create patterns of spiritual discovery for Afrolatinx authorship, activism, and creative expression.

The effervescence of espuma del mar, sea-foam, signifies the tangible yet ephemeral qualities of using conjure as a tool of inquiry. Sea foam helps us think through the shifting nature of the multiple experiences of modernity, science, spirituality, and materiality that Afrolatinx spiritual communities face. Elements of our natural world are intertwined in profound ways with the spirit as we engage more and more in virtual existence and decentered notions of place. Espuma del mar also references the sea foam of research—how sizzling and tickling sensations experienced during ethnographic moments leave traces of memory in notes, rituals, and stories, illustrating the subtle nature of some of the flows explored in this project.

I want us all to think of rituals like la letra del año as creating residual transcriptions, left-behind clues that serve as testaments to experiential bonds that are both visual yet hidden in Afrolatinx religions. By evaluating how divination creates new modes for interpreting ecological phenomenon, gender, and temporality, I am suggesting that we reconsider our methodologies for coping with loss and fear from the perspective of the residual flows that Yemayá and her seascapes invoke. These flows reveal, as Karin Amimoto Ingersoll suggests, a “seascape” way of knowing, where “waves are constantly formed and broken, sucked up from the very body that gave it life” (in Waves of Knowing, 20). This sentiment of fluid motion reveals the ocean’s lessons in rethinking ecological kinships, and the consequences of human irresponsibility.

“I want us all to think of rituals like la letra del año as creating residual transcriptions, left-behind clues that serve as testaments to experiential bonds that are both visual yet hidden in Afrolatinx religions.”

Archives of conjure search for traces of history in such waters, ones that can recall spirituality, sexuality, and gender as revealed in mythology and storytelling. In doing so, a diversity of cultural ecologies, spiritual histories, and shared ways of being come to light in ways that urge future searches, connections, and enactments. Archiving based on heightened ritual experiences expresses our need to connect with the past and the ephemeral: it is about feeling through the body in the here and now through the dead. In weaving together these different threads, like the beaded mazo for water divinities that adorns the cover of the book, my project recognizes waters’ movements and currents as productive guides for understanding unapologetic mutability and sensuality. Like Yemayá’s righteous anger that started this blog, the prophetic desire for healing, balance, and course correction is a distinctive trait that belongs to the sea in world mythology and cultures—even more so for Afrolatinx communities, where Yemayá and the ancestors are real and the forces that shape our world can be understood through water.