The Problem with History

“Think of official history as a book. A book comes into view; it seems to suggest that it has no blank spaces, no margins. But it does, it contains blank spaces. In those spaces I cram my own notes, copious notes that are not yet articulated thoughts, and in the end weave a new book solely from the notes in the margins.” — Hideo Furukawa

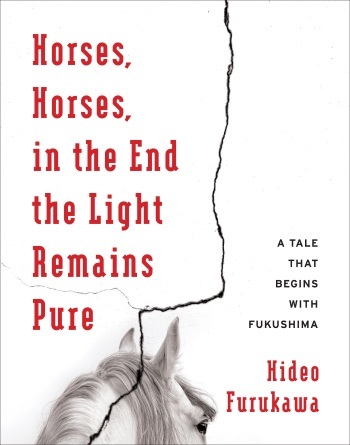

Our World Literature Week celebration continues today with a focus on Zhu Wen’s Horses, Horses, in the End the Light Remains Pure: A Tale That Begins with Fukushima, translated by Doug Slaymaker with Akiko Takenaka.

Hideo Furukawa is in New York this week with Monkey Business for the PEN World Voices Festival (along with other fantastic writers, editors, and translators), and will be participating in a number of events: April 27 (Wed.), New York University, 6:30pm; April 28 (Thur.), Kinokuniya Bookstore, 6pm; April 29 (Fri.), BookCourt, 7pm; and April 30 (Sat.), Asia Society, 2pm (Ticket purchase required)! And now, on to the post:

Five years ago, on March 11, 2011, the town of Fukushima, Japan, was struck by a devastating earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident. Over 20,000 people died.

The reconstruction has been swift. ‘The incident is about to be forgotten, or they pretend nothing has happened,’ Japanese writer Hideo Furukawa said about his hometown. For Furukawa, careful examination is the only route to healing. One must investigate one’s nation and its past and present. His new book, Horses, Horses, In the End the Light Remains Pure: A Tale that Begins with Fukushima, is a mix of fiction, history, and memoir, as one can see in this short excerpt.

The Problem with History

Hideo Furukawa

Our history, the history of the Japanese, is nothing more than a history of killing people.

I am not sure of the best way to phrase things, given that rather inflammatory start. I will explain things as simply as I can. We live within the echoes of the Warring States period. For example, bushō, the term for military leaders, circulates as a commodity in contemporary society, and, thus, it continues to echo in everyday Japan. By the “Warring States period” I include the Azuchi Momoyama period right up to the beginning of the Edo period (1573–1603). I am not sure if the Azuchi Momoyama period is still taught as a single historical period in schools (elementary, middle, and up through high school). But I am quite sure that everyone learns that there was a period when Oda Nobunaga and then Toyotomi Hideyoshi ruled supreme. For example, we consume these two men as commodities all the time. When I say we “consume” them as commodities, I mean how we see them as “heroic” and think of them positively. Why would that be? These two were a rare form of military leader, which is also to say, on the other hand, and precisely because of that, that they were a rarely seen form of murderer. I can lay out details from the historical record. I will use both reign-era names and Western calendar dates. In the second year of Genki (1571) Nobunaga burned down the Enryakuji Temple compound outside Kyoto, murdering three to four thousand people. Among them women and children who had begged for mercy. Those very women and children were, one by one, beheaded. In the second year of Tenshō (1574), Nobunaga crushed the Ikkō-ikki uprising in Echizen. More than half of those that were confined by the siege were driven to starvation, and then, to give but one example, he built multiple fences around their compound to cut off all exits and then set fire to the entire thing, from all sides. More than twenty thousand people were burned to death. He would not even consider their requests for surrender. In the third year of Tenshō (1575), Nobunaga crushed the Ikkō-ikki uprising in Nagashima. He wrote of this in his own hand: “Nothing but corpses in the towns.” This in a letter addressed to the military officer stationed in Kyoto.

He murdered thirty to forty thousand people.

That’s the kind of man that that Oda Nobunaga was. How can we see him as heroic?

…

Our history is nothing more than a history of killing people. What do you think of that? I am hoping it sounds more straightforward this time. If so, I can proceed without catchy summaries. Anyway, the real issues are ahead. When history is treated as “official national history,” it is almost inevitable that you are going to get biases. Our love of our own history produces in the collective populace the power to suppress, perhaps unconsciously—perhaps even consciously—inconvenient facts. This is not the intentional undertaking of a particular individual (or thing) but a covering up, accomplished almost automatically, via an anonymous filtering system. Official history is, by definition, a filtering system. All the more reason why these bushō military leaders are consumed to this extent. I wonder if I possess the skills to resist this. History that has the ability to jolt us: that is ideal—what I consider ideal—history.

Think of official history as a book. A book comes into view; it seems to suggest that it has no blank spaces, no margins. But it does, it contains blank spaces. In those spaces I cram my own notes, copious notes that are not yet articulated thoughts, and in the end weave a new book solely from the notes in the margins.