Hospice of the Creative Class

By Alex Sayf Cummings

“From tobacco and plow to computer and creative economy, this rich and eloquent history shows how a group of civic leaders put rural North Carolina at the forefront of the postindustrial revolution. In California, they say Silicon Valley is one of a kind; this marvelous book proves otherwise.”

~Fred Turner, author of From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

Welcome back to the Columbia OAH Virtual Book Exhibit.

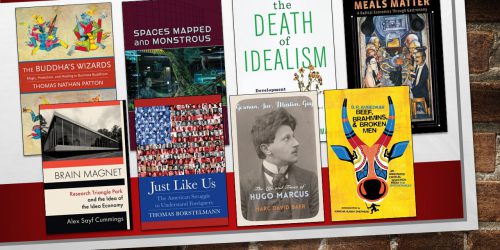

This month, we’re publishing Alex Say Cummings book, Brain Magnet: Research Triangle Park and the Idea of the Idea Economy. It’s the story of the academics, business people, and politicians in the 1950 who set out to remake North Carolina’s low-wage economy into the first iteration of the American knowledge economy. Alex also edits the online culture magazine Tropics of Meta, which most recently set off the controversy around American Dirt. In this guest post adapted from ToM, she explores how the coronavirus crisis proves that an economy that only rewards and protects the most privileged workers is vulnerable to collapse.

• • • • • •

No event has so starkly revealed the brutal inequalities of contemporary capitalism as the coronavirus pandemic. The professional-managerial class gets to work from home and tweet busily about how tough it is to be under lockdown, at home with their kids—while still being paid. Meanwhile, low-wage workers either have to go to work and risk their lives, or lose their jobs and everything else too: their homes, their savings, their health insurance (if they even have any). As CNBC’s Annie Nova pointed out in 2019, “40% of Americans would struggle to come up with $400 for an unexpected expense”—and are thus one lost paycheck or accident or illness away from complete destitution.

Here comes one big, big accident.

It feels like an emperor-has-no-clothes moment. It turns out that a large swath of the white-collar workforce might have what the anthropologist David Graeber artfully termed “bullshit jobs.”

It also feels like the end of an era. The belle epoque of neoliberal capitalism may be sputtering out. Since the 1970s, liberalized trade and new technology have made the world ever more interconnected; most of the former communist world was swept into the global market system. Hundreds of millions in countries such as India and China rose out of dire poverty, even as deindustrialization, offshoring, and automation gutted the stability that the working class and middle class in North America and Western Europe had come to expect in the years after World War II.

“Everything was faster, cheaper, more efficient, and more innovative, and anyone who complained about the new order needed to get back in line.”

Everything was faster, cheaper, more efficient, and more innovative, and anyone who complained about the new order needed to get back in line. “There is no alternative,” neoliberal icon Margaret Thatcher said in the 1980s. “The world is flat,” intoned the mustachioed tribune of elite conventional wisdom in the 2000s. (Curiously, the original cover of Thomas Friedman’s 2005 book shows old-fashioned ships sailing off a cliff—a more fitting metaphor than the author perhaps realized.)

The 2008 financial crisis was the first big shock to the system. The Great Recession showed how rapacious greed and a state too attenuated or unwilling to regulate it could cause the infrastructure of global capitalism to buckle and nearly collapse. The U.S. government rushed to shove hundreds of billions of dollars into its financial institutions and stave off a crisis of Great Depression scale—and American capitalism essentially returned to business as usual during the presidency of Barack Obama. His successor could crow about a go-go economy in early 2020, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average reached its highest ever value (29,551.42) on February 12. With a historically low unemployment rate, the sitting president seemed like a formidable incumbent in the upcoming 2020 presidential election.

Few could have guessed that we would be discussing potential unemployment of 20 percent or more just a month later.

I sketch out this story to bring attention to the critical fact of economic inequality. Historians and social scientists have long recognized that the gap between the very affluent and everyone else has been growing since the 1970s, as forces such as deindustrialization, globalization, the decline of the labor movement, and the deregulatory policies of the Reagan-Clinton era have led to dazzling gains at the top of the income spectrum and stagnant wages for the middle class and working poor. All of this was cause for angst among critics on the Left, as figures ranging from writer Barbara Ehrenreich (in 2001’s Nickel and Dimed) to economist Thomas Piketty (in 2013’s fluke hit Capital in the Twenty-First Century) pointed out the dangers of an increasingly unequal capitalist economy.

“Few could have guessed that we would be discussing potential unemployment of 20 percent or more just a month later.”

Defenders of the status quo had their own arguments. It didn’t matter, they said, how the pie was divvied up as long as the pie kept getting bigger. Economic inequality, in this view, is only relative: it might bother me that Jeff Bezos and Jamie Dimon have vastly greater wealth than I, but that doesn’t mean I’m doing badly. And neoliberal capitalism seemed to keep growing that pie. The experts in Silicon Valley and Wall Street were smarter than we were, and with their new apps and financial “products” they would make us all happier, healthier, and richer. (“Fitter, happier, more productive…”)

I wrote a book, Brain Magnet, about how all this came to be—how Americans developed a vision of the world, beginning in the 1950s, that elevated a class of highly educated “knowledge workers” to preeminent status and held technological innovation as its highest value. Scientists and engineers, artists and experts—the group that urbanist Richard Florida would dub the “creative class” in his influential 2002 book—were the driving force of the new capitalism, particularly as the deindustrialization of the 1970s and 1980s gave way to an information economy. My book used North Carolina’s Research Triangle as a case study of how this view of the world evolved and came to dominate policy and public discourse in the late twentieth century, but it is the story of all our lives in the capitalism of recent decades.

The creative class is, by and large, at home under quarantine right now, and we are left to contemplate what our economy is and who it is for. For the moment, truck drivers and nurses are doing the essential work to keep us all alive. Science will, we hope, lead to a cure or vaccine for the virus in due time, and we will again be grateful for technological innovation. But the crisis also shows that the neoliberal world of global free trade and fast capitalism is far more vulnerable than most of us realized.

And a political economy that only rewards, protects, and prioritizes the most educated knowledge workers while leaving the working class behind to suffer and die is not as sustainable as most elites were content to believe just a few weeks ago. When it comes to matters of equity, justice, and basic human decency, there is not an app for that.