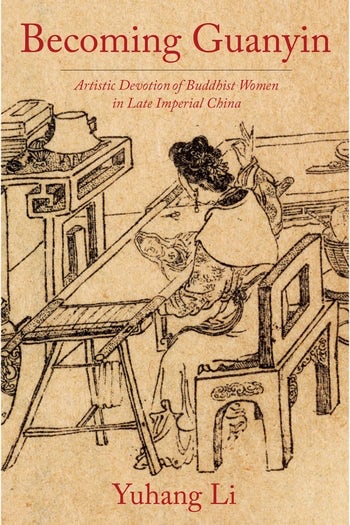

Yuhang Li on Becoming Guanyin

“Yuhang Li is, by training, an art historian. However, her take on Guanyin goes beyond the realms of art history. Li analyzes the female portrayal of Guanyin through paintings, material culture of embroidery, theatrical display of dance, archaeological objects, scripture, and literature. This is truly an interdisciplinary work.”

~Chün-fang Yü, author of Kuan-yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokitesvara

In today’s Women’s History Month post Yuhang Li, author of Becoming Guanyin: Artistic Devotion of Buddhist Women in Late Imperial China explores how Buddhist women used the production of art as a way to approach the bodhisattva Guanuyin.

Remember to enter our month-long drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book!

• • • • • •

I begin this book with a straightforward question, “What did lay Buddhist women in late imperial China do to forge a connection with the subject of their devotion, the bodhisattva Guanyin?” This question is not as simple as it appears. I journeyed a long time before focusing on the often-overlooked women’s roles in the production of art and began to inquire how women established their religious authority in making and using material objects as a way to approach to Guanyin. The length of my journey is mostly due to the fact that material practice and women’s things were not recorded in historical documents and were also unnoticed by modern scholars.

My intellectual path to the current stage can be traced back to my experience of learning Chinese painting in high school. My painting teacher frequently complimented me by saying that my brushstrokes were so forceful that they did not seem like they emanated from a female hand. Although I was not clear about the supposed difference between female and male brushstrokes, I still internalized his words as a standard of good painting, and for a long time, I prided myself on not drawing like a woman. I attended college at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and majored in Art History. Regardless of whether we were studying Western or Chinese Art History, most of the artists we read about were male (fortunately, this is not the case anymore). Given the ubiquity of male artists, most students, including myself, took it for granted that artists were men. This gendered perception was challenged after I graduated from college and started working at the Beijing Art Museum. There I had several revelatory experiences concerning women, art, and religious practice. While I was cataloging collections, I encountered a great deal of painting, calligraphy, and embroidery created by women. While I was writing the scholarly catalog Buddhist Sculptures from Ming and Qing Period, I came across many documents and objects related to lay Buddhist women and the cult of Guanyin in late imperial China. Moreover, the museum is located in a Buddhist temple, which was commissioned and later renovated by several Empress Dowagers during the Ming (1358-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

“Although I was not clear about the supposed difference between female and male brushstrokes, I still internalized his words as a standard of good painting, and for a long time, I prided myself on not drawing like a woman.”

Consequently, I started to realize that although women have not been regarded seriously by the canon of Chinese art history, the material objects and physical structures they created, patronized, and used are quietly arranged on the shelves in museums or silently staged there. After I started graduate school in the U.S., I learned that as early as 1988, the leading art historian Marsha Weidner already curated the first exhibition dedicated to the women artists entitled Views from Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists 1300-1912 and published a catalog under the same title. From the 1990s to the first decade of the 21st century, many pioneer scholars such as Susan Mann, Dorothy Ko, Francesca Bray, Grace Fong, Judith Zeitlin, Beata Grant, Dorothy Wong, and Hui-shu Lee further explore women’s agency in controlling their lives through literary creations and artistic patronages. My book pays tribute to these and many other scholars of Chinese women’s history. Following the trajectory of these scholars, my book discusses how women controlled their own bodies through the process of making and using religious icons.

Guanyin (Perceiver of Sounds)—also known as Avalokiteśvara (the Bodhisattva of Compassion) —was originally a male deity in India but was gradually indigenized as a female deity in China during a span of nearly a millennium. Following her feminization and sinicization, Guanyin became the most popular female deity in the Ming and Qing periods. Building on Chün-fang Yü’s groundbreaking book Kuan-yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokiteśvara (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), Becoming Guanyin will help advance the level of knowledge about the impact of Guanyin’s sexual transformation on practitioners, especially laywomen. This book is not about the gendered transformation of Guanyin, but treats the consequences of this gendered transformation, specifically how this feminized deity influenced believers with respect to their gendered identities. I look at how the female form of the bodhisattva provided a visual frame for lay Buddhist women to create a direct bodily connection with the divine through the processes of self-, object-, and world-making.

“Women used the power or efficacy of their own body to echo that of Guanyin.”

Unlike previous scholarship on late imperial Chinese women’s religious practices, which focuses primarily on textual sources, Becoming Guanyin is the first book to grant precedence to the actual objects created and used by women as a more immediate point of entry to studying how women fashioned their gender identities in relation to a feminized deity. It listens to subaltern voices by focusing on practices and things rather than exclusively on texts. By investigating the process of making and using things, I hope to help readers to understand how women linked themselves to religious icons and how raw materials were transformed into a cultural artifact, from profane into sacred. The process of this transformation is gendered in the Chinese cultural context in the late imperial period because the material, the skill, the subject, the motivation for making, and the function of the object can all be directly linked to the creator’s body. Women used the power or efficacy of their own body to echo that of Guanyin. In particular, I use case studies to demonstrate how lay Buddhist women pursued religious salvation through creative depictions of Guanyin in different media such as painting and embroidery, and through bodily portrayals of the deity incorporating jewelry and dance. Becoming Guanyin tells stories of individual women’s struggles in their lives to solve various problems such as how to produce a child; how to face the life when her husband passed away; how to cure her own or her mother in-law’s illness; how to become a proper principle wife and so on. All these issues were solved in the process of making or mimicking Guanyin icons.

Save 30% when your order a copy of Becoming Guanyin, or any of our Women’s History Month featured titles, from our website by using coupon code: CUP30 at checkout!