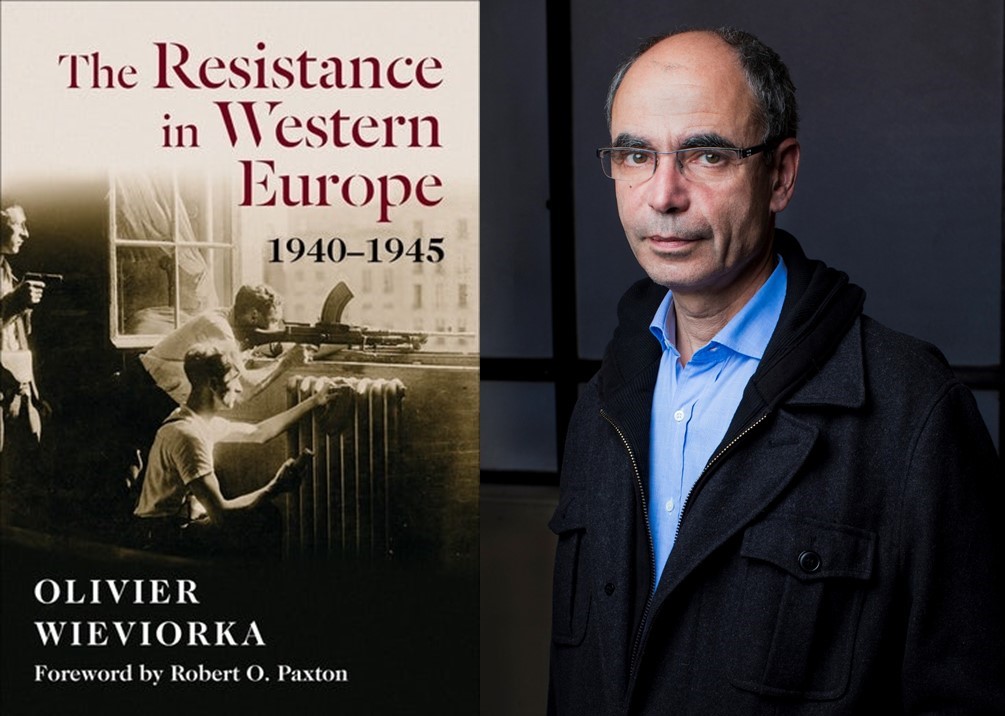

Yuri Pines on Translating The Book of Lord Shang: Apologetics of State Power in Early China

“No one in the world is more qualified than Yuri Pines to present this new translation of the infamous The Book of Lord Shang, which has both fascinated and repelled readers throughout Chinese history. Accompanied by a superbly informed study of Lord Shang’s place in his political context and the reliability of the text attributed to him, this is sure to be the standard translation for decades to come.”

~ Paul R. Goldin, author of Confucianism

Our first featured title for National Translation Month, is a canonical work of early Chinese theology that is a rarely find in the scholarly community. In the guest post below, Yuri Pines, who translated The Book of Lord Shang: Apologetics of State Power in Early China, by Shang Yang dives into his experience translating this work and discusses the challenges of translating its bold language and a minimalist style.

If you’re interested in continuing to expand your understanding of global political philosophies, be sure to enter our drawing for your chance to win a copy of the abridged version of the abridged version of The Book of Lord Shang.

• • • • • •

The Book of Lord Shang (Shangjunshu 商君書) occupies an odd place in studies of early Chinese political thought. On the one hand, its putative author, Shang Yang 商鞅 (d. 338 BCE), is widely credited as an outstanding, even if controversial, statesman, whose reforms propelled the state of Qin to the position of supremacy in the fragmented Chinese world of the Warring States period (453-221 BCE). He is also recognized as a founder of the so-called Legalist School of thought (fajia 法家), one of the major intellectual currents in early China. Almost any textbook in Chinese history and thought will therefore duly contain references to Shang Yang and to the Book of Lord Shang. On the other hand, in-depth studies of the Book of Lord Shang are few and far between; and even translations of the text into European languages are very rare. Paradoxically, the text associated with the singularly important reformer in the history of pre-imperial China seems to attract little interest in the scholarly community.

The reasons for the scholars’ reluctance to engage Shang Yang and “his” (actually, his and his followers’) book are not difficult to discover. The Book of Lord Shang appalls the reader with a series of highly provocative statements. It proposes to let “villains … rule [the] good,” derides fundamental moral norms such as “filiality and fraternal duties, sincerity and trustworthiness, integrity and uprightness, benevolence and righteousness” as “parasites,” and advocates military victory by performing “whatever the enemy is ashamed of.” Many readers will be further alienated by the text’s repeated assaults against intellectuals as useless “peripatetic eaters” who should be radically suppressed if the state is bound to prosper. Add to this Shang Yang’s notoriety as promoter of merciless punishments and as endorser of cutting off enemy’s heads as the most meritorious deed—all these may well explain why traditional China’s literati (and not a few modern scholars) were “ashamed to speak of Shang Yang.”

“The Book of Lord Shang appalls the reader with a series of highly provocative statements.”

Yet despite all its negative aspects, I believe that the Book of Lord Shang deserves more scholarly engagement and for sure merits an updated translation cum study. First, the magnitude of success of historical Shang Yang makes glossing over his and his followers’ ideas untenable. Second, the appalling statements are not the book’s essence, but, rather, a rhetorical device aimed at distinguishing the text from the dominant moralizing discourse of its age and emphasizing the novelty of its message. Alienating rhetoric aside, the Book of Lord Shang presents a series of highly interesting ideas—from the concept of historical evolution to the novel view of human nature, to the controversial concept of “social engineering”—which for sure merit scholarly engagement. Third, notwithstanding the literati’s dislike, the book’s vision of empowering the state by establishing total control over its material and human resources had a lasting impact on Chinese statesmen. As such, the book deserves closer scrutiny. It is my hope that the new translation cum study of the text will make the Book of Lord Shang more accessible not only to historians of China but also to all those interested in comparative political thought.

Translating the Book of Lord Shang is not easy. The text is notoriously terse. It abounds with sentences that comprise four (and sometimes only two) words, and is often written in an almost slogan-like fashion. This minimalism is a deliberate choice of the authors who deride useless “argumentativeness” and prefer straightforward statements over literary embellishments. The translator faces a dilemma. Preserving the text’s laconism may make it barely comprehensible for the modern audience; but doing away with it would betray the authors’ conscious choice of style. My choice was to remain faithful as much as possible to the original’s style, adding whenever necessary extra words in square brackets and explaining the meaning of terse sentences in the endnotes. The result may be less pleasant literarily speaking but it allows the reader to appreciate better the original’s flavor.

“The text is notoriously terse. It abounds with sentences that comprise four (and sometimes only two) words, and is often written in an almost slogan-like fashion.”

Another problem is that of translating several keywords. A single Chinese character ming 名 may refer to a person’s name, to one’s reputation, to social status, to the items of legal codes, to bureaucratic nomenclature, and so forth. Should I translate each of the appearances of the term ming differently, the reader would miss the text’s skillful utilization of the term’s multivalence. My solution was to provide whenever possible the single translation of ming as a “name,” adding whenever necessary explanations in brackets or footnotes. Once again, the faithfulness to the original’s style is more important in my eyes than the literary quality of the translation.

To sum up, my translation did not aim to make the Book of Lord Shang a literary masterpiece. It was surely not. Yet I hope that my translation allows the reader to appreciate the novelty and boldness of the text’s message and evaluate anew pluses and minuses of Shang Yang’s and his followers’ thought.