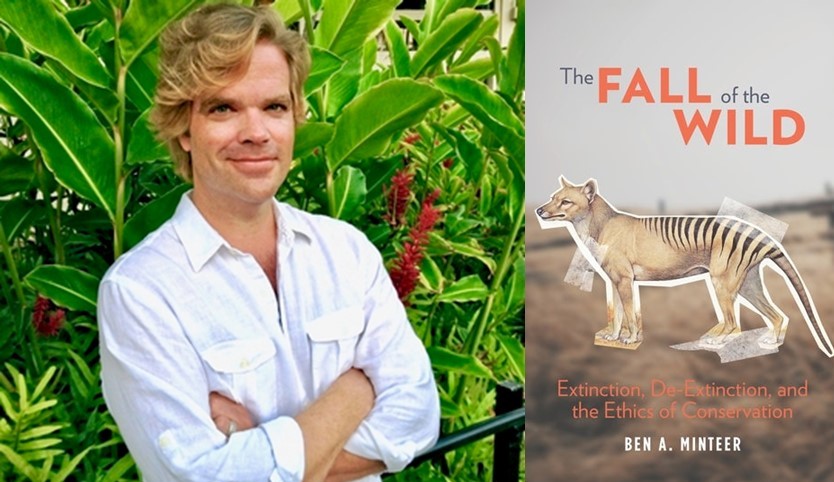

Q&A: Ben A. Minteer on The Fall of the Wild

“What to do—and not to do—about the biodiversity crisis that we ourselves are engineering? In The Fall of the Wild, Ben Minteer takes us through the options. His assessment of the situation is balanced, clear-sighted, and humane.”

~ Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History

The following is an excerpt of an interview with Ben A. Minteer, author of The Fall of the Wild: Extinction, De-Extinction, and the Ethics of Conservation, that originally appeared on the ASU website. In this conversation, Minteer discusses the moral and ethical issues involved in the erosion of the wild and bringing back extinct species.

Enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of The Fall of the Wild.

• • • • • •

Bringing back extinct species: If we can, should we?

Q&A with author Ben A. Miniteer

Q: Around the world, animals, plants and insects are dramatically declining in numbers and may go extinct. In fact, many people believe we are experiencing a sixth mass-extinction event. Some scientists say “de-extinction technology” could be used to bring back extinct species. Yet this would not change human behavior, which likely caused the problem in the first place. Could you discuss?

Ben A. Miniteer: Well, as I write in the book, I don’t think we would really be bringing back extinct species such as the Tasmanian tiger or the passenger pigeon. We may eventually be able to create facsimiles of these animals through genetic tinkering, but to my mind, they’ll be new species, animals de-coupled from the natural history of the original forms. Still, you raise an important point, and it’s one of the main themes of “The Fall of the Wild.” There’s a sense in which these “fixes” elide the hard questions and deeper lessons of extinction, which are more wrapped up in our environmental values and lifestyles than in a technical exercise in gene editing.

Q: In the book, you discuss an “authentic ecological conscience.” What do you mean?

Miniteer: I borrowed this from the great conservationist-philosopher Aldo Leopold, who observed that moral obligations have no meaning without the compulsion to do the right thing even when no one is looking. It’s a quaint expression, but it captures a powerful idea about moral responsibility. Leopold’s notion of an ecological conscience serves as a touchstone in my book, helping me understand why, for example, the collection of specimens from newly discovered or re-discovered species may be risky — or why conservation efforts to relocate species in advance of climate change are insufficient if they don’t address larger ecological and social maladies.

Q: What about the issue of unintended consequences? There are many examples in science where an invention or new technology was initially wonderful, but then unexpected issues became new problems.

Miniteer: It’s an anxiety that runs through “The Fall of the Wild,” though the unintended consequences I’m most concerned with have to do with our environmental character. Will we be able to maintain respect for a wild nature that we are increasingly manipulating, controlling, even attempting to re-create via genetic engineering? So, the “fall” I’m worried about is really twofold: the loss of wild species and places in the human age, certainly, but also the fading of the wild as an ethical ideal.