My Time at CUP: Mark Fortier

“What I did come to expect and treasure every day was a dedicated team of editors and marketers devoted to great scholarship, a love of books, and a spirit of camaraderie that made me feel at home and made me feel proud.“

Mark Fortier

FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT, FORTIER PUBLIC RELATIONS

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1994–1998

- PUBLICITY MANAGER

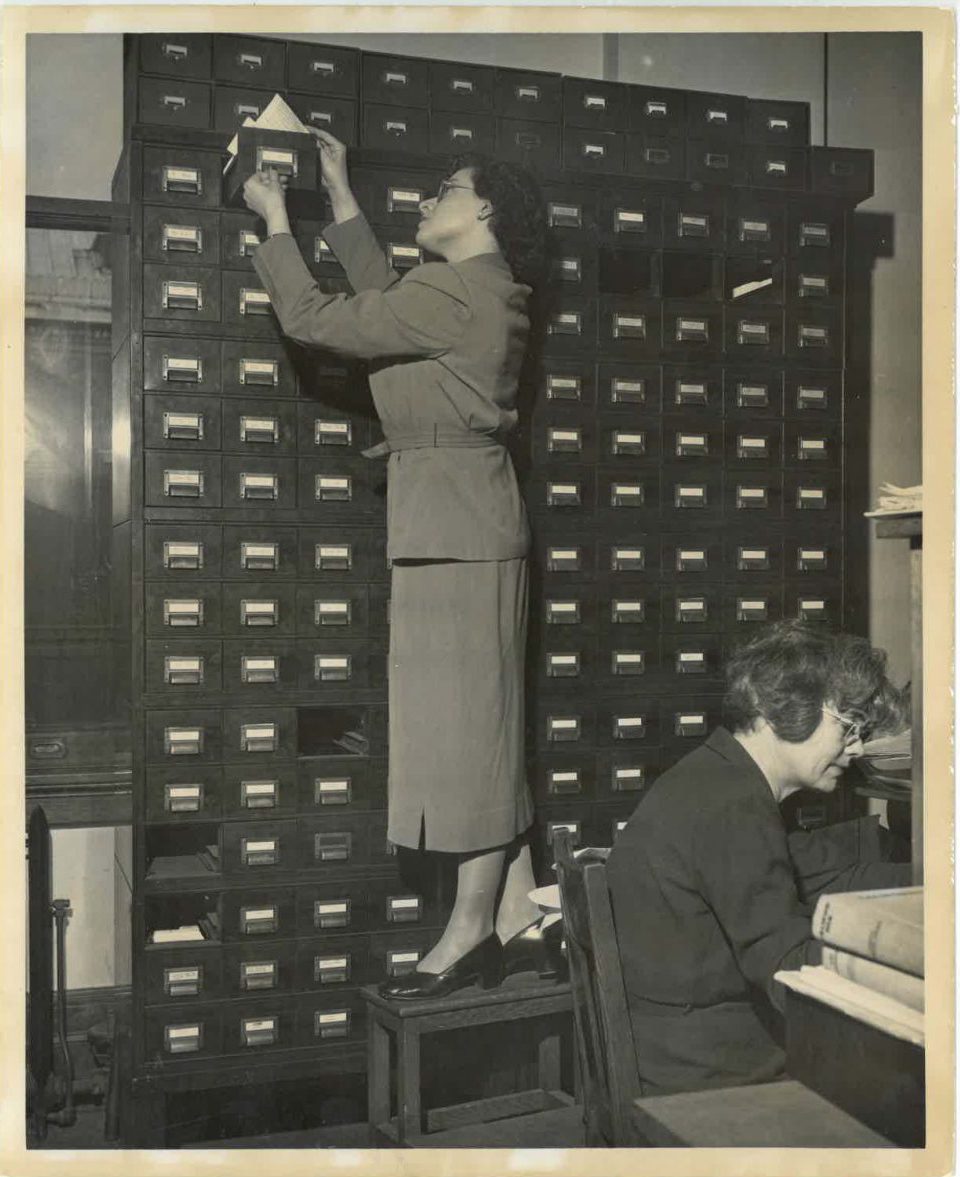

> When I was offered the job as publicity manager at Columbia University Press in 1994, I looked forward to two things: a return to the noble ideas of academia that I had cherished in college and an escape from the commercial pressures of being a publicist at Penguin USA, where one could be fired if the sales goals weren’t met on books on such varied topics as how to bake your own Twinkies and erotica for couples. To be hired at Columbia University Press felt like getting admitted to the Ivy League that had rejected me as an undergraduate. I would be wearing the royal robes of prestige, gravitas, and serious scholarship. But not everything lived up to this image. The shabby offices on the bottom floors of a college dormitory on 113th Street did not provide the most inspiring first impression. But I soon discovered that Columbia University Press was ahead of its time, a pioneer in publishing CD-ROMs and developing other digital resources, though being first didn’t last long. However, what was more enduring was Columbia’s introduction of the Boolean search for its flagship publication, the Columbia Encyclopedia. It was a precursor to Google and still influences the way I search for information online today.

While I was glad to leave behind the commercial trade books at Penguin USA, I reveled in trying to get mainstream crossover media attention for Columbia’s scholarly books that might otherwise only be reviewed in such specialized academic journals as International Journal of Nordic Reindeer Husbandry. But I would also grow frustrated trying to explain to academics who were indeed Oprahs of the field of semiotics that the real Oprah had no idea who they were.

So I was disappointed when it took several weeks for me to find out that a producer from the real Oprah show had called about one of our books. The receptionist was so excited to get a call from the all-powerful Oprah that he thought it would be better to transfer it to the editor in chief’s voicemail instead of to me, the publicist, even though she was on vacation for two weeks. Despite the embarrassing delay, we still got our author on Oprah, and I still use the story as an example of why PR success depends not just on landing a great opportunity but also on acing the opportunity at hand. Unfortunately, the author had not been media trained, so when his intro came and the camera turned to him for his big moment on national TV . . . he appeared as though he was picking his nose. Alas, this Oprah appearance didn’t end up selling as many books as we had hoped.

If there ever was an Oprah of her field it was Julia Kristeva, one of Columbia’s most prolific and best-selling authors. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that she was the Grand Dame Diva of French theory. Unfortunately, it was at a fancy lunch hosted by the Cultural Services of the French Embassy that I learned that my role as Julia’s publicist was to sing her praises, which I wasn’t yet very skilled at. I naively thought my purpose there was to indulge in the Beaujolais and coq au vin and didn’t realize that instead I should have introduced her with a laudatory speech. I had already drunk my glass when she raised hers to introduce herself. Oops.