Thursday Fiction Corner: The Conflict between North and South Korea, on an Intimate Scale

Welcome to the Columbia University Press Thursday Fiction Corner! This week Ani Kodzhabasheva, a PhD candidate at Columbia University, reflects on Yi Mun-yol’s novel Meeting with My Brother and current events.

Are you confused by the barrage of threats launched daily from North Korea towards the United States, and vice versa? Following the news on the issue has shown me that I’m not the only one. Even policy analysts and military strategists can seem at a loss.

One of this week’s attempts to explain the situation in Northeast Asia is a New York Times piece that takes us to Yanji and Dandong, two cities on North Korea’s border with China. The reporter, Chris Buckley, talks to locals and tourists in an attempt to gauge their mood. What do they think of North Korea? Of the United States? His brief conversations reveal some of the anxieties that those in the region deal with on a daily basis.

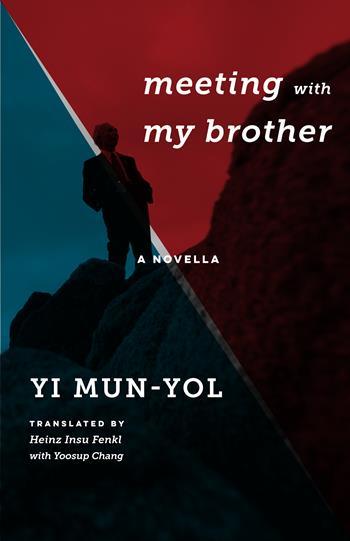

But, as is often the case, there is more to the story than one can glean from the news. In fact, the people of Yanji have been affected by North and South Korea’s political fluctuations for decades, and the precariousness of international relations in the region has more or less persisted since the onset of the Korean War. Yi Mun-yol’s novel Meeting with My Brother, set in Yanji in the early 1990s, shows that the city has long been subject to secret police spying, as well as a base for legal or not-so-legal cross-border exchange. In Yi Mun-yol’s novella, the South Korean narrator encounters his half-brother from the North for the first time, and the traumas of Korea’s division play out on an intimate scale.

The plot of Meeting with My Brother unfolds over just a few days in Yanji—in a hotel, a couple of restaurants, and on the bank of the Tumen River, which separates North Korea and China. Within this tightly delineated setting, Yi weaves together multiple narratives that create a microcosm of whole societies torn apart by military and ideological conflict. In addition to the two long-lost brothers, Yi populates his novella with a Chinese Korean woman from Yanji who is bitter about the prejudice she experienced in the South; the overly zealous “Mr. Reunification,” who often bores his companions with his utopian pronouncements; and a cynical businessman engaged in mysterious trade with the North.

Struggling to make the best of their predicaments, Yi’s flawed characters can sometimes make you laugh, although the overwhelming mood is one of reflection and mourning. Yi shows to what extent our lives are shaped by historical events much larger than us and how, at the same time, these events demand of us that we take a moral stand. During his stay in Yanji, the narrator, who first approaches his long-lost brother with a sense of pity, is forced to reckon with his own life choices.

The little book is written in a dispassionate, reportage-like tone (the narrator is a professor of history in Seoul), yet it carries a surprising emotional heft. Several characters who boast a certain ideology—be it capitalism or communism, nationalism or pro-American beliefs—are brought by the events in Yanji to a new sense of humility. Nobody leaves without any scars, or a bit of redemption. Fiery rhetoric gives way to self-doubt, as the encounters in Yanji make clear that the Korean War has left no absolute winners and losers. Hyeok, the North Korean brother, struggles with jealousy; the narrator, Professor Yi, begins to confront his suppressed guilt about the way he achieved his success. The struggle to communicate leads to many dramatic reversals, as certain words or memories elicit pain or misunderstanding.

The book provides no clear answers about politics, diplomacy, or the future of the Korean Peninsula. It is these very conflicts, which are once again crowding the news today, that are being dramatized in Meeting with My Brother. Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker that “There is no moral to Yi’s story.” That is essentially true. Yet, in the end, the moral is that political divisions have a human dimension and that, in order to understand history and how it shapes current events, we need to look beyond the political agendas of the day.

At this historical moment, Meeting with My Brother’s finely crafted story gives us an occasion to ask ourselves, What would it be like to empathize with people in North Korea? Yi Mun-yol’s narrator, through his self-exploration, serves as an example of how that radical question might be answered.