The Nation Calls

“Diana listened to her husband’s end of the conversation from the entrance to the kitchen, where she was standing. She understood at once that he was talking to Margaret Marshall, the literary editor of The Nation. She quickly surmised that Marshall was asking her husband if he had any candidates who might be interested in writing unsigned reviews of novels for the magazine. As soon as Lionel hung up the receiver, she walked over to him, smiled, and surprised herself by asking if she would be a suitable candidate. She wanted to be in the running.” — Natalie Robins

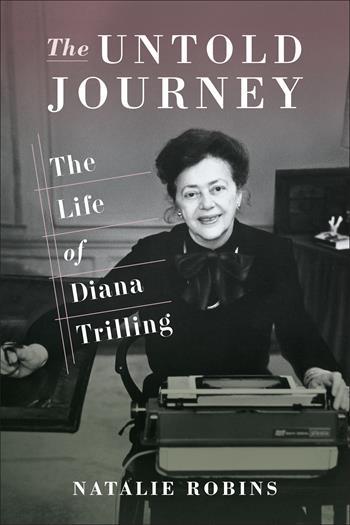

This week, our featured book is The Untold Journey: The Life of Diana Trilling, by Natalie Robins. Today, for the final post of the feature, we are happy to present an excerpt from The Untold Journey in which Robins talks about the Trillings’ Partisan Review parties (featuring Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt, Elizabeth Hardwick, Meyer Schapiro, Alfred Kazin, and others) and about how Diana started reviewing books for The Nation.

The Nation Calls

By Natalie Robins

In 1937, two years before his book on Arnold was published, Lionel began writing for the new, Communist-free Partisan Review, a magazine whose strong intellectual and cultural influence would last for decades. It was edited by William Phillips and Philip Rahv, two men who had first met at meetings of the John Reed Club. Both men, and their wives, would become close friends of the Trillings.

Diana, gratified by her husband’s accomplishments, nonetheless began to feel very uncomfortable at the Partisan Review parties they attended. Her views were overlooked in discussions by and large because she was not a writer, at least not a published one. “If you went in as a wife, which I did in the early years of my married life, they [the parties] were hell,” she later told the writer Patricia Bosworth. Mary McCarthy, who was listed on the masthead of the first issue of Partisan Review, wrote an occasional theater column for it, and at the time was living with Rahv, especially snubbed Diana. McCarthy focused all her attention on Lionel. But Lionel did not enjoy being in her spotlight. “What makes an intelligent woman suppose that the way to attract a man is to be rude to his wife?” Lionel asked Diana, as she reported in The Beginning of the Journey. She later made clear that despite everything, “Lionel never got upset about anything that happened to himself the way he got upset if something went wrong for me, and I felt that way about him.” This was because of “their extraordinary mutuality,” and “extraordinary alikeness.” They had fierce and spirited minds and a powerful sense of loyalty that transcended their acute emotional difficulties.

Mary McCarthy, along with the political theorist (as she liked to be known) Hannah Arendt, and later on, the critic and novelist Elizabeth Hardwick, and the historian Bea Kristol, writing under her birth name Gertrude Himmelfarb, all had “honorary membership” in Partisan Review, Diana told Bosworth. And “they all weren’t friendly at all,” even though Himmelfarb and Diana would, for a long while, become pretty good pals. But in general, in the late 1930s, and for several decades after, there was no sisterhood. As for Arendt, Diana said that she “never said hello to me in her whole life. I guess she wanted to go to bed with Lionel. That was usually the reason when women weren’t pleasant to me.”

The parties “were primarily political,” Diana told Bosworth, although intense flirting, the initiation of affairs, and heavy drinking all tied for first place. “Every time you went to a party you were flirting, flirting, flirting,” Diana later elaborated. “Whether you did anything about it or not, that was what you were there for. Parties were for sex. They were for exploration,” although she and Lionel considered themselves part of “the famous puritanical group.” She did not name the other members.

The men were dubbed “The PR Boys,” the women “The PR Girls.” The “Boys”—Rahv, Phillips, Elliot Cohen, Meyer Schapiro (the art historian), and the writers Max Eastman, F. W. Dupee, and later Alfred Kazin and Delmore Schwartz—always led, while the “Girls,” even if published writers, always took a secondary role. There was very little loyalty or patience among them all and a great deal of competitiveness and envy. The gatherings could be exhausting, and if the party included dinner, afterward the men usually retreated to another room for cigars and brandy while the women stayed behind, gossiping, sharing political news, dabbing at their lipstick, or sometimes helping to clean up.

One late afternoon in January 1941, the phone rang in the ground floor apartment at 620 West 116th Street. The drapes were already closed, although the apartment was always dark and gloomy-looking. Lionel, just home from his class, picked up the phone, which was on a table in the hallway leading to the back of the apartment. Diana listened to her husband’s end of the conversation from the entrance to the kitchen, where she was standing. She understood at once that he was talking to Margaret Marshall, the literary editor of The Nation. She quickly surmised that Marshall was asking her husband if he had any candidates who might be interested in writing unsigned reviews of novels for the magazine. As soon as Lionel hung up the receiver, she walked over to him, smiled, and surprised herself by asking if she would be a suitable candidate. She wanted to be in the running. Lionel immediately agreed that it was a very good idea, though he mentioned that Marshall had a graduate student in mind for the job. He said he would speak to her but insisted that if Diana didn’t work out for some reason, she should receive “no preferential treatment.”

Diana liked the fact that the reviews would be unsigned so she could still cling to her father’s ever-haunting proscription “against any form of self-display” (excluding family concerts with her siblings, and her aborted singing career, which her father had once callously proclaimed belonged in the toilet.)

At her next psychoanalytic hour Diana mentioned the potential Nation job, emphasizing her pleasure and relief at having unsigned reviews. There would be no fear of showing off. She was safe from harm. Dr. Ruth Brunswick, listening carefully for a change, suggested that perhaps Diana was hiding behind her father in an attempt to cover up her real objective, which was to have her name all over the magazine. Diana very quickly recognized the truth presented to her. “I always felt secure about my intelligence,” she said, “much more secure than I felt about my exhibitionism. . . and I didn’t have any doubt in my ability to do the work for The Nation.”

There was one other matter—her name. Diana Rubin? Or Diana Trilling?

While married, she had once or twice signed her name to documents as Diana Rubin, but she felt more comfortable with Trilling. Lionel agreed that if she got the job (and she did), she should use Trilling. But some of the “PR Boys” had something to say to him privately: wouldn’t she be an embarrassment to Lionel? Diana’s insecurities had already translated into a haughtiness they disapproved of. They were dead serious about their objections. Lionel dismissed their warning and looked the other way, as he always did in such cases.

So at the age of thirty-six Diana began a career that seemed at first a whim but would become the “sustaining,” she said, focus of her life.

And by 1942, the same year that her hostile acquaintance Mary McCarthy published her first novel, The Company She Keeps, Diana would have her own signed column, which, as a matter of fact, she had asked for, and Margaret Marshall had immediately agreed to.