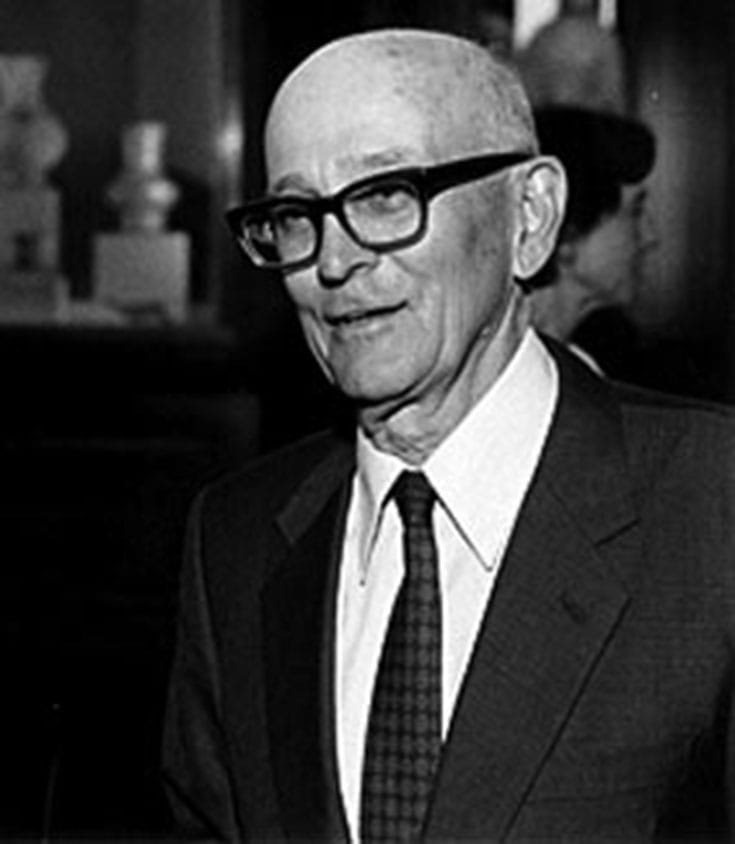

On Burton Watson (1925-2017)

The following post is by Jennifer Crewe, associate provost and director of Columbia University Press. As an editor she worked with Burton Watson for 30 years before his death earlier this month.

Burton Watson died a few days ago, and with his passing the world has lost one of its greatest translators. Burton was one of the only people who possessed the extraordinary ability to translate equally well from both Chinese and Japanese. In fact, one of the early anthologies he translated and edited for Columbia University Press was Japanese Literature in Chinese, a title that puzzled me greatly when I first arrived at the Press, knowing nothing about Chinese or Japanese literature. Burton was deeply familiar with both languages and cultures. He started learning Japanese while serving in the U.S. Navy and stationed in Japan during World War II (as did several giants in the field of his generation, including Donald Keene and Wm. Theodore deBary, also seminal Columbia figures who created the Columbia Asia program and started the Press’s list in East Asian civilizations). After Watson’s discharge he enrolled at Columbia and received his Ph.D. in Chinese literature in 1956. The Press published a revised version of his dissertation, Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Grand Historian of China, beginning what would be a sixty-year relationship.

In addition to working freely in both languages, Burton also moved easily from premodern classics (his Zhuangzi, originally published in its Wade-Giles version in 1968, is still one of the Press’s best-selling books) to works from the modern period. He was at home translating a similarly wide range of genres, from ancient history (Records of the Grand Historian of China) to philosophy and religion (Analects of Confucius and The Lotus Sutra), to literature (Tales of the Heike and Selected Poems of Du Fu).

I marveled at his ability and at his copious production. When he finished one book and sent it to me, there was often a period of silence; then he would write and ask what I thought he should translate next.

I once heard a story, perhaps apocryphal, told to me by someone who visited Burton’s Tokyo apartment and watched as he sat at his manual typewriter looking at whatever book he was translating and simply typing the translation as he read the original, without having to look up any words. As a nonspeaker of Chinese and Japanese, I rely on experts to tell me whether a transition is an accurate and faithful rendition of the original. But as a reader I rely on my ear. It was clear to me that Burton was an avid reader of American poetry—particularly of the Williams era. His translations, particularly of poetry, are concise, deceptively simple, and evocative. And they employ the language of everyday speech, which is why they are so successful with students. Burton’s translations opened up the world of East Asian culture to countless students and general readers. Over the years I would occasionally hear criticisms—Watson’s translations were not “scholarly” enough. Burton eschewed notes, and it was often difficult to coax even an introduction out of him. But his translations will last because of the simple beauty of his English idiom. Many “scholarly” translations do not display that inner beauty. Burton’s translations seem effortless. He strove for that.

By my count Columbia University Press has 41 books in print with Watson’s name attached to them. I have been at the Press 30 years, so that is how long I knew Burton. I got acquainted with him slowly, by means of old-fashioned letter-writing. He would send me carefully typed pale blue aerograms, which I would open with trepidation lest I accidentally tear off any of his prose, which was friendly, spare, and efficient, sometimes with a note of petulance—“I don’t suppose you liked my last manuscript much”—if I had failed to respond promptly to what he’d sent. I never saw his apartment, but I always imagined him sitting in a barely furnished Japanese-style room, with the typewriter, and later the computer, in the center on a small desk, and with books all around.

My relationship with Burton remained mostly epistolary on into the e-mail era, when his messages were shorter and lost a bit of flair, but I did see him several times when he came to Columbia for a semester some 20 years ago, and then twice in Tokyo more recently. The last time I saw him was in 2012, and he seemed in good health and rather chipper. He took me on a long walk through the Imperial Palace Gardens, and it seemed to me that he could go on walking forever.

All day

In the mountains

Ants too are walking

From For All My Walking: Free-Verse Haiku of Taneda Santoka

Translated by Burton Watson

11 Responses

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thank you, Jennifer, for this splendid poem about Buron

To Jennifer Crewe,

Thank you so much for your post, which describes Professor Burton Watson’s life in such concise and evocative sentences as his translations of poetry.

Yes, he liked walking, and even while he lived in Tokyo he walked to many places quite far from his house without taking a bus or a train.

He lived in many places other than Tokyo in Japan, starting with Kyoto while he was a graduate student. I visited him at his residence many times while he lived in Osaka, Wakayama, and Niigata Prefecture. I think He knew the map of Japan better than any ordinary Japanese.

Dear Madame:

Happen to meet with Professor Watson years ago during his second visit China and have been carefully in doing some reading of his works. And great man of devotion and respected Translator of so many Chinese Classics. We own our thanks to him for whatever he has done.

May he live in peace.

For Jennifer Crewe

Thank you very much for your post on Professor Watson. While I never met Professsor Watson I had the honor of participating in the publication of “China at Last,” Professor Watson’s 3 week personal diary of his first visit to China, published by Seven Grasses Publishing House and Hiromu Yamaguchi who accompanied him. While the book is a marvelous account of his journey through China after a 30 year wait, the real reward is getting to know this brilliant scholar on a very personal level. The book is an insightful and delightful read!

Burton was a delight to know. His untroubled demeanor, his kindly tone when addressing friends in Japanese, his pleasure upon receiving a gift–and for his publisher–his endless productivity and taste. What luck it is to have known him.

It is so wonderful to read these remembrances and tributes to Burton Watson, who I knew as “Unkie.” He was a very sweet man of obvious great depth and intelligence, and he treated me as one of the Dundon family, of his sister Janet Dundon. I was honored to get to know him well, as the best and lifelong friend of his nephew William Dundon. I just learned of Unkie’s passing from William, and shared memories of this great but unassuming man with him. I still have the copy of poetry and prose of Po Chü-I that Unkie gave me one Christmas, and it introduced me to Asian poetic style. This enlightenment eventually led to my interest in haiku. The concision and elegance of the Asian style forever turned to a strong preference for economy and simplicity. He also introduced me to the fun that could be had in poetry and prose. I will miss him, and this ever hardening world has lost yet another paragon of grace, humility and humanity.

Editor – In writing using thumbs, I managed to accidentally drop the words “my taste” after “forever turned” in my comment. If you should use my comment, kindly make that correction for me, and any others you might see that have resulted from the same difficulty in writing using thumbs only (and suffering from failing eyesight)! I trust your judgment. Oh, and please use my entire name, Roger Wilcox Cloud. Thank you.

Jennifer —

That was a wonderful tribute. I know you’ve known Burton for a long time, because you’ve often spoken fondly of him. A great translator must know at least two languages extremely well. Burton’s gift was his ability to articulate his understanding of East Asian texts in English.

I have taught his book Early Chinese Literature frequently over the past 25 years or so. This is the book that epitomizes Burton Watson for me. Students love it. It’s sort of halfway between translation and interpretation. And, of course, it’s not just literature in the strict sense. It is a text well before its time.

Dr. Watson will be missed. I think he lived a full life (91 years!) doing that at which he excelled. Is it wrong to feel joy that he lived, rather than sorrow that he has passed?

I remember him best for a poem he translated in the late 70s. If not for his translation I would never have encountered the poem. If his translation hadn’t been so perfect, I would never have remembered the poem.

It was called “The People”, and one of the stanzas went like this:

“Science without you (the people) is coldhearted

Philosophy without you is barren

Art without you is empty

Religion without you is merciless”

He always knew just the right word and never got carried away by the urge to “decorate”. There is no finer translator than the one who is well-read and has a supple vocabulary on which to draw. Dr. Watson, I am talking about you.

Thank you for your work, and thank you for your inspiration!

*The poem is by Daisaku Ikeda and was published by Weatherhill (Tokyo) in 1978.