Whose Identity? Which Politics?

“Even when museums like the NMAAHC explore into painful content like racial violence and terrorism, it is seen as delving for the purpose of presenting a resilient identity narrative. And they do. But so does the National Museum of American History in its presentation of Americana, from Dorothy’s ruby red slippers to the two hundred year-old flag from the American Revolution. The relegation of museums like the NMAAHC to the stuff of identity politics neutralizes those driven by white nostalgia.” — Robyn Autry

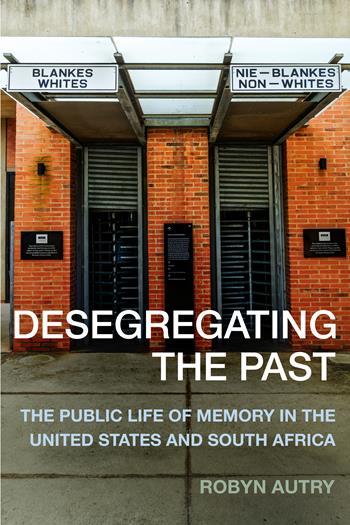

The following is an excerpt from an article by Robyn Autry, author of Desegregating the Past: The Public Life of Memory in the United States and South Africa, originally posted at the Huffington Post.

Whose Identity? Which Politics?

By Robyn Autry

In the weeks following the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in late September, a historic presidency ended, and then hundreds of thousands of people converged on the National Mall as another shocking one began. The NMAAHC hosted a widely popular alternative inauguration organized by Busboys and Poets, increasing its symbolic power as a place of resistance and celebration. How can we make sense of the throngs of people still flocking to the Mall to visit that nation’s first black history museum in a political climate openly hostile to so-called identity politics?

The NMAAH is not an identity museum per se. Neither is the National Museum of the American Indian, nor the Latino and Asian Pacific history museums also under consideration. Or, at least they are no more driven by the desire to celebrate identity than the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum or the National Museum of American History, or even the National Air & Space Museum. In fact, all historical products, whether they be national museums or history textbooks, contain facts and fictions about who we are, or dream of being in relation to lives already lived and lost and those still in the making. In effect, they all offer different interpretations of how great America was (or wasn’t) and how we can all do better.

While there is nothing wrong with projects aiming to interpret or represent collective identities, ‘identity-driven’ is a label used to distinguish them from those museums viewed as more objective or less biased. Museums dedicated to representing the lives and cultures of people of color are seen as self-affirming celebrations that some see as divisive and fixated on what makes us different. Critics also charge that these museums offer less historical context and material evidence or artifacts, relying instead on personal testimonies, multimedia displays, and sweeping summaries. In short, they are thought to be touchy-feely. Even when museums like the NMAAHC explore into painful content like racial violence and terrorism, it is seen as delving for the purpose of presenting a resilient identity narrative. And they do. But so does the National Museum of American History in its presentation of Americana, from Dorothy’s ruby red slippers to the two hundred year-old flag from the American Revolution. The relegation of museums like the NMAAHC to the stuff of identity politics neutralizes those driven by white nostalgia.

…

After decades of political maneuvering, fundraising, and development, the NMAAHC opened on September 24, 2016. Televised and streamed online, the extraordinary occasion was marked by heartfelt words from President Obama, Congressperson John Lewis, Oprah Winfrey and Will Smith, and musical performances of Stevie Wonder, Patti LaBelle and Angélique Kidjo. Even more noteworthy, were the 30,000 ordinary people who visited the first weekend, and the tens of thousands who have followed them. With lines circling the building, the museum has been so popular that timed-passes are still being used to manage crows and to allow more people to traverse the 350,000 square foot museum. The passes available online are booked through June 2017, with a limited number being offered for same-day visitors.

How can we account for such keen interest in the museum, from the millions of dollars raised to the thousands of people clamoring to get inside? It’s as much about an insistence that identity is indeed political, as it is about collective yearnings to see that which has been kept off limits, to venture into those spaces that unsettle official accounts and expose the social fissures we already fully know exist.

…

Read the article in full at the Huffington Post.