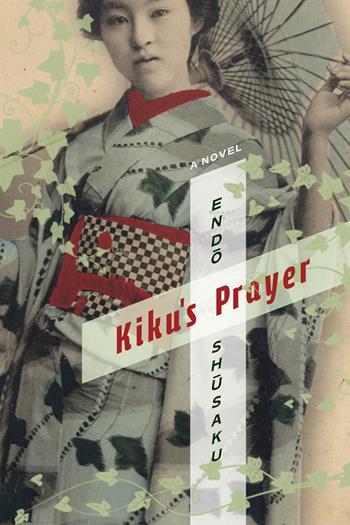

Thursday Fiction Corner: Kiku’s Prayer by Endō Shūsaku, translated by Van C. Gessel

Welcome to the Columbia University Press Thursday Fiction Corner! This week Russian Library and Asian Humanities editor Christine Dunbar shows once again that you can take the girl out of the Russian department, but you can’t take the Russian department out of the girl.

I recently read the novel Kiku’s Prayer by Endō Shūsaku, in Van C. Gessel’s translation. We published Kiku’s Prayer in 2012, shortly after I started working at the Press, but I picked it up now because of the publicity surrounding Martin Scorsese’s film adaptation of another Endō novel, Silence. Endō was Catholic, and both novels center on Christians in Japan during the Edo period, when, as of 1614, Christianity was outlawed. Silence takes place in 1639, directly after the unsuccessful Shimabara Rebellion, in which many Christians took part and after which persecution intensified. Kiku’s Prayer, on the other hand, is set at the end of the Edo period, at the moment of transition between the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration in 1868. At this point, the remaining Japanese Christians (Kirishitans) have been practicing in hiding for over 200 years. A French priest arrives, searching for them like rumored pirate treasure (yes, there’s a post-colonial aspect to this novel too), and while he eventually finds them, he leads the local officials right to them as well. As the political situation becomes more tangled, the officials become less and less sure how to deal with these unrepentant law-breakers. As Endō is an historical novelist par excellence, this would be enough of a reason to read Kiku’s Prayer, and Van C. Gessel’s sparse but fascinating notes point out characters based on historical figures for readers whose knowledge of the period is spotty. But at its heart, the novel is an investigation of faith, personal ethics, and the question of how to live in a world that contains so much suffering.

It’s at once a novel saturated with Christianity and Christian suffering—it’s impossible to shake the subcontext of Jesus on the cross, not to mention Catholicism’s long history of martyrs—and a novel that leaves lots of room for parallel ethical decisions. For Endō, ethics is not the sole purview of Christianity, or, to put it a slightly more Christian-centric way, Christian belief is not a prerequisite for Christian behavior. The titular Kiku is a young woman who falls in love with Seikichi, one of the hidden Kirishitans. Kiku herself has little use for Christianity, which she rightly fears will lead to trouble for her beloved. Nonetheless, when Seikichi is taken away and tortured in an attempt to force him to renounce his faith, Kiku prostitutes herself, first to one of the officials overseeing the torture, and later to others in order to earn money for bribes and food for the prisoners. In doing so, Kiku endures pain and humiliation, ostracizes herself from her family, and sacrifices her very future with Seikichi, to whom she believes she can no longer make a proper wife. She carries on an outwardly heretical but authentic relationship with the Virgin Mary, whom she sees as the other woman, in the sense that she has stolen Seikichi’s love. This is the opposite of the tension between outward quiescence and inner rebellion that recurs throughout the novel, from Father Petitjean’s promise, immediately broken, not to proselytize to the Japanese to the officials’ promise that the apostasy of the tortured Kirishitans need be in word only.

For me, the pleasure of the novel is heightened by the references Endō makes to that other author obsessed with faith and doubt, Fyodor Dostoevsky. These references are fluid—in most ways, Kiku is nothing like Sonia Marmeladova, though both turn to prostitution to help relieve the sufferings of others—but specific textual moments makes such parallels clear. Lord Itō Seizaemon, for instance, gets drunk in a tavern on Kiku’s money, and then wails to his companions about his wretched nature, much in the manner of Marmeladov with Raskolnikov in the tavern, drinking away Sonia’s earnings. At other times, Itō more closely resembles Dostoevsky’s Underground Man. He is jealous of his bureaucratic peers, who are more successful, and veers between pity and cruelty towards those under his power. He even has moments of clarity, as when, leaving the teahouse where Kiku works, he says to himself: “I’m…I’m a despicable man. A truly despicable man.”

Endō and Dostoevsky share common concerns regarding logic, faith, evil, and forgiveness, but I wonder if the turn to the Russian author might not also be motivated by the process of writing an historical novel. After all, in 1868, when Kiku’s Prayer takes place, Notes from the Underground (1864) and Crime and Punishment (1866) would have just come out. Clearly, now I must read Silence to see if Dostoevsky’s anachronistic influence can be felt there.

Click below to read the first chapter of Kiku’s Prayer. In this excerpt, Kiku is still a child, but the promise of her later bravery can already be seen.