Interview with Brian T. Edwards, author of “After the American Century"

“Culture jumps publics all the time in the digital age, and what it means and where it goes is completely unpredictable. Diplomats are well aware of the technologies by which to spread culture in the twentieth-first century, but they have not yet caught up with the logics of the circulation of culture in the digital age.”—Brian Edwards

The following is an interview with Brian T. Edwards, author of After the American Century: The Ends of U.S. Culture in the Middle East

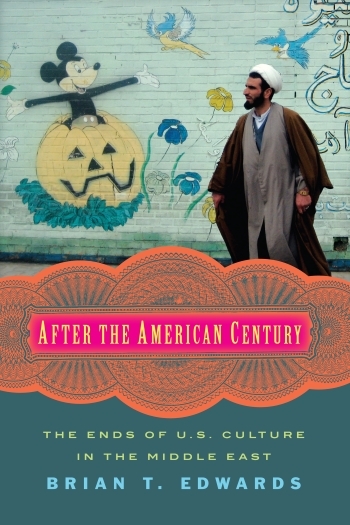

Question: Is that a real photo on the cover or is it photoshopped?

I took the cover photograph in Isfahan, about 200 miles south of Tehran. Isfahan was once one of the major cities of the world, twice the capital of Persia, and is filled with architectural masterpieces from the Safavid dynasty with a city square that is simply breathtaking in its scale. So when I turned a corner and came across this mural, with Mickey Mouse popping out of a jack-o-lantern and Walt Disney birds, it struck me that America was another empire that had left its mark on this city—part of the urban landscape now, with people passing by going about their daily business. Maybe it was the pumpkin, but there was something autumnal in that fading mural that hinted at the passing of the American empire.

I showed the photo to one of my Iranian students. He said it reminded him of the walls in the kindergartens and nursery schools when he was growing up, where pictures of Mickey Mouse were painted everywhere. The Simpsons were popular too, he said. It was expensive to buy notebooks and school supplies with these American cartoon characters, while the walls were free. Later in the book (page 117), I include a photo I took of a food court in a Tehran shopping mall, where you can see a similar phenomenon with Shrek, another American cartoon character who has had a profound impact in Iran.

Q: What does the book’s subtitle mean? Why “ends”? Do you mean to suggest that American culture is no longer present in the Middle East?

BE: Quite the opposite! By using the plural of the word “end,” I meant to evoke its multiple meanings—endpoints, uses, meanings, aims. I did also mean to nod at the meaning evoked by “end” in the singular (that something might come after the end of the American century). What I’m interested in discovering in this book is what it means that US culture is popular in the Middle East, almost part of the fabric of life, even while the United States as a political entity is increasingly unpopular. But unlike during the Cold War, or the so-called “American century,” when people like Henry Luce and the US State Department wanted to leverage the popularity of US culture, it now means a lot more than Coca Cola, jeans, or jazz music. Of course American culture still refers to Hollywood movies and hip hop, both of which are popular in the Middle East and have inspired local artists. But American cultural products in the digital age also include platforms like YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook, and cultural forms that are recognized by people in different parts of the world as “American”—say a movie formula, like the teen romance, or action-hero comic books, or cyberpunk. All of these end up in popular culture in the Middle East and North Africa, where they become new things, ultimately unrecognizable to American culture itself. So I’m really interested in what this all means, what the “ends” of these versions of American culture are, where they “end” up.

Q: What’s the deal with Shrek?

BE: Shrek makes two extended appearances in the book and shows different routes a particular cultural object can take in the digital age. In Tehran, I was startled to keep coming across images of the green ogre, from the food court at the shopping mall in the north part of the city to 2-by-3 foot Persian-language books retelling the Shrek story. Most interesting were the competing dubbed versions of the different Shrek movies—some of them more illegal than others—about which people had very strong feelings. I had come to Iran in part to try to understand the debate over the film director Abbas Kiarostami, but instead became obsessed with figuring out what one of my informants meant when she said that Shrek was really an Iranian movie.

I came across a very different Shrek in Morocco, where a hugely popular Moroccan video pirate artist used it in his most famous work. The video pirate, named Hamada, took a dance scene from Shrek and dubbed a popular Moroccan song over the soundtrack. The work that resulted, which became known as Miloudi after the singer whose work was dubbed over a clip of Donkey singing, started a phenomenon in Morocco in the mid 2000s and launched Hamada’s underground career.

Q: Morocco, Egypt, and Iran seem like very different places. How did you choose them as the primary sites for your book?

BE: I chose to focus on three very different countries—and in particular Casablanca, Cairo, and Tehran, their largest cities—because each has a different relationship to the United States politically, and because the meanings of American culture differ in each. Morocco has long been an ally of the US—it was the first country to recognize the sovereignty of the independent US, which makes many Moroccans proud—and American culture was for many Moroccans, until recently, a liberating alternative to French and Spanish colonial attitudes. Iran has been openly antagonistic to the US since the 1979 revolution, and Iranians are well aware of the ways in which the US overthrew the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, which put US pleas for democracy in the Middle East in an ironic light for many Iranians. Egypt, the largest Arab nation and a major recipient of US foreign aid, calls itself mother of the world (umm al-dunya) and has a sense of its exceptional status that is reminiscent of American exceptionalism. Plus Egypt had a major film, TV, and culture industry with a transnational reach. Despite their differences, these three countries are not meant to be representative of the entire Middle East, itself a category constructed by outsiders. Rather I wanted to push back at the idea—which I find common in US media—that evidence from one “Arab” or “Muslim” country or community can stand in for a vast and diverse region.

Q: What’s the matter with Homeland?

BE: I have been watching Homeland since it first started its run, so I understand its appeal. While the opening credits take pains to connect the drama to the recent history of US involvement in the Middle East, it is of course an elaborate fiction. The errors and overreaches are worth correcting, and the representation of Islam is retrograde if not outwardly racist. But the biggest problem with Homeland is that it provides an elaborate justification for keeping the so-called war on terror going and (in the first three seasons, which aired 2011–2013) for maintaining a hardline approach to dealing with Iran. So Homeland does for American audiences what Orientalism did for British citizens during the period of high colonialism: it justifies the presence of US military in the region and manages its US audience’s discomfort about the ongoing wars and occupation in the Middle East. This is the cultural work done by the series, which I find unfortunate.

Q: What are the implications of your book for cultural diplomacy?

BE: Cultural diplomacy is based on the idea that the realm of culture (by which is generally meant art, music, literature, and sometimes academia) offers an alternate means by which to exchange ideas. In principle this is a concept any reader or consumer of culture would agree with. And we’re all consumers of culture, whatever we do in our day jobs. The problem for me is when the state tries to get overly involved with pushing the cultural products—trying to harness the “soft power” of American culture—for geopolitical ends, as has happened during both the Bush and Obama administrations. This turns American culture from something expressive to tools of persuasion in order to pave the way for or soften the blow of US foreign policy. But American culture’s message is not so clear or didactic—in fact, as many students in the universities in Middle East and North Africa know, US literature and music is often oppositional to the policies of the state (think Henry David Thoreau, Martin Luther King, or Leslie Marmon Silko, or Public Enemy in hip hop). More to the point, young Arab and Iranian consumers of culture hardly need the US government to sponsor official culture tours or electronic journals. Hackers, digital pirates, and downloaders are everywhere, and the Middle East is filled with savvy consumers of culture and an especially talented pool of digital navigators. Culture jumps publics all the time in the digital age, and what it means and where it goes is completely unpredictable. Diplomats are well aware of the technologies by which to spread culture in the twentieth-first century, but they have not yet caught up with the logics of the circulation of culture in the digital age. I’ll take this up in a blog here tomorrow.