Has Hillary Really Helped the World’s Women?

“On the one hand, the doctrine that Clinton made a central part of her time at Foggy Bottom was revolutionary; never before had the cause of women been elevated to a priority of American foreign policy and labeled a key national security concern. But talking the talk is not the same as walking the walk, and as Clinton prepares for a presidential candidacy in which she will likely tout both her tenure at State and her potentially history-making role as America’s first woman president, it is only natural to examine whether the “Hillary Doctrine” really worked.” — Valerie M. Hudson and Patricia Leidl

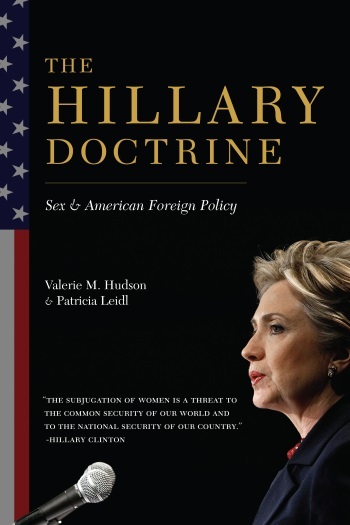

This week our featured book is The Hillary Doctrine: Sex and American Foreign Policy, by Valerie M. Hudson and Patricia Leidl, with a foreword by Swanee Hunt. Today, we are happy to present an excerpt from The Hillary Doctrine that originally ran in Politico Magazine.

Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway for a chance to win a free copy of The Hillary Doctrine!

Has Hillary Really Helped the World’s Women?

By Valerie M. Hudson and Patricia Leidl

Many leaders have had doctrines named after them—from the Monroe Doctrine to the Truman Doctrine to the Bush Doctrine—but so far there’s only that can be ascribed to a woman: the Hillary Doctrine. As Hillary Clinton herself defined it, “the subjugation of women [is] a threat to the common security of our world and to the national security of our country.”

But for proponents of this doctrine, perhaps no irony was crueler than seeing its namesake, then Secretary of State Clinton, smiling broadly in her trademark pantsuit as she walked the red carpet from her plane in Riyadh with the Saudi foreign minister, Prince Saud al-Faisal, in 2010. The moment brought to mind an incongruity no less extreme than if Frederick Douglass had been appointed ambassador to the Confederacy and found himself sipping tea and making small talk with Nathan Bedford Forrest. For, in Saudi Arabia, the subordination of women is as peculiar and pernicious an institution as was slavery in the antebellum South.

It wasn’t the last time Hillary Clinton was accused of brushing aside her own self-declared commitment to women’s rights, ostensibly in the name of the national interest. Most recently, as she prepares to launch her all-but-declared presidential campaign, reports have emerged concerning large donations to her family’s foundation from countries including Algeria, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and, of course, Saudi Arabia—a rogues’ gallery of governments with poor records on women’s issues. How could Clinton—she of “women’s rights are human rights” fame, who by all indications will soon try again to break the “highest, hardest glass ceiling” of the White House—still be so cozy with a regime so at odds with one of her core, lifelong causes?

On the one hand, the doctrine that Clinton made a central part of her time at Foggy Bottom was revolutionary; never before had the cause of women been elevated to a priority of American foreign policy and labeled a key national security concern. But talking the talk is not the same as walking the walk, and as Clinton prepares for a presidential candidacy in which she will likely tout both her tenure at State and her potentially history-making role as America’s first woman president, it is only natural to examine whether the “Hillary Doctrine” really worked. Last week, amid the furor over her email server, Clinton was marking 20 years since her own groundbreaking 1995 speech in Beijing on women’s rights. But the anniversary also raised an important question: Two decades later, are the world’s women better off for Clinton’s efforts on their behalf—or were those efforts mostly for show?

Perhaps no other country offers a better test case than Saudi Arabia, a regime that openly denies women so many rights and yet appears to be chummy with both Clinton and her foundation. Asked last week specifically about Saudi Arabia’s donations to the Clinton Foundation, the former secretary of state, fresh off a speech about women’s rights at the United Nations and the release of a 50-page report on the status of women and girls in the world, responded, “There can’t be any mistake about my passion concerning women’s rights here at home and around the world. So I think that people who want to support the foundation know full well what it is we stand for and what we’re working on.”

Should we take Clinton at face value?

Some context is worth considering first: Saudi Arabia ranks 145th of 158 countries in the U.N. Development Program’s Gender Inequality Index, making it among the worst countries in which to be born female, despite its considerable oil wealth. Child marriage is not uncommon because there is no legal minimum age to wed. For the bride, consent isn’t even required, and indeed, a woman (or girl) need not even be present for her own marriage, as long as her male guardian and her groom agree.

In the past few years, however, women in Saudi Arabia have made modest gains. In 2011, Saudi women finally gained the right to vote and to run in municipal elections (though not until this year). Today, 20 percent of the King’s Consultative Council (Majlis as-Shura) is made up of women. In 2012, women were permitted to work as sales clerks in lingerie and cosmetics shops for the first time, and in October 2013, four Saudi women were licensed to become lawyers—a first in the history of the kingdom. Overall, the number of women in the workforce has increased nine-fold in the past five years, to 17.7 percent, compared to 74.1 percent of males.

Mobility is still one of the most vexing problems facing Saudi women. The government forbids them to drive (apparently in deference to their ovaries, which must not be harmed). The mutaween (religious police) enforce a strict dress code that stipulates that women be covered top to bottom in the stifling black abaya and accompanied by a male guardian (mahram) every time they stir outside the home. Women cannot wander about by themselves, ride a bike (unless in a park, in full abaya and with a male guardian present) or go on a picnic. They cannot travel outside the country nor marry a man of their choosing without the permission of the ubiquitous male guardian.

The watchful eyes of male relatives and the dreaded mutaween circumscribe women’s every movement—so much so that in a 2009 cable to U.S. diplomats, Wajeha al-Huwaider—a Saudi women’s rights activist who recently challenged the ban on female drivers—was quoted as calling the country as “the world’s largest women’s prison.”

It wasn’t always this way. Before extremist clerics, calling themselves the Ikhwan, or the Brotherhood, took control of the Grand Mosque at Mecca in 1979, women enjoyed a modest measure of autonomy. As one Saudi woman expressed it in Qanta Ahmed’s 2008 In the Land of Invisible Women, “I used to be free in Riyadh, walking around [with my hair uncovered]. … Can you believe … I used to walk alone in Riyadh: no man, no maid, just relaxed like in Paris?.”

Many argue that it was only after the Saudi military ended up laying siege to one of Islam’s holiest sites in order to oust the recalcitrant fanatics, resulting in three hundred deaths and hundreds of injuries during two tense weeks, that the status of Saudi women changed dramatically. The crisis convinced the monarchy that it needed the fundamentalist Wahhabi clergy more than ever to control the population and to subvert insurgency by playing to the most atavistic elements in Saudi society. Unfortunately, the price for appeasement was the increased subordination of women.