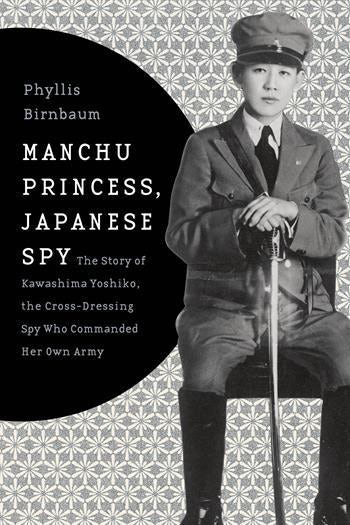

Interview with Phyllis Birnbaum, author of "Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy," Part 1

The following is part one of our interview with Phyllis Birnbaum, author of Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy: The Story of Kawashima Yoshiko, the Cross-Dressing Spy Who Commanded Her Own Army:

Q: How does Yoshiko Kawashima’s life inspire such divergent, polarizing views?

Phyllis Birnbaum: Yoshiko spent her life shuttling between China and Japan, and even now her reputation is very different in these two countries; this is all the result of Yoshiko’s activities during the Second Sino-Japanese War. For the Chinese, she is still held up as a case of all-purpose evil, a traitor who schemed against China and caused damage that can never be forgotten. To this day, they blame her for starting a war in Shanghai and for otherwise assisting the Japanese occupation. They emphasize the lurid sides of her biography, pointing to the alleged childhood rape by her adoptive father as the cause of an unquenchable sexual thirst and full-scale perversion.

For Japanese, her story takes on another look entirely. In Japan, she is accepted as almost one of their own since she spent much of her youth in the country. Therefore, in Japan, they take a more wistful view of Yoshiko’s escapades. The Japanese emphasize her psychological problems—childhood woes, abandonment, solitude. The Japanese tend to forgive her wartime activities and don’t dwell on the rape rumors. They see Yoshiko as a pitiable character, wronged over and over, by her birth father, her adoptive father, the entire Japanese military establishment, and other males who took advantage of her beauty and her daring.

Q: Part of the difficulty of portraying Yoshiko seems to lie in her own affinity for toying with the truth and fabricating myths. Which traits did she tend to emphasize?

PB: Yoshiko made up different stories about herself at different times of her life. Her disregard for the truth must bring despair to the heart of any biographer. In one particularly outrageous interview, she showed such a stupendous disregard for the facts that she called into question every word she had ever uttered about her personal history. Gall unremitting, falsehoods pouring forth, Yoshiko told about how she was the daughter of the last emperor of China and had been “disguised as a boy to save her from Chinese revolutionists who went to Japan to seek her life.” She was shot three times in the Shanghai Incident and “was carried away as dead, but miraculously recovered.” Her parents were killed in the Chinese revolution of 1911, and her brothers drowned or were poisoned or stabbed. She added that she piloted airplanes, was an ace with a pistol and rifle, could write magazine articles, played musical instruments, sewed, painted, and composed Japanese poetry. Also, she was ready to assume leadership of China, if summoned.

Yoshiko’s embellishments, taken together with the wild newspaper accounts about her during her lifetime, would make the work of tracking down the facts hard enough, but there’s also the 1933 best-selling Japanese novel based on her life that many people—including the judges at her trial for treason—took as her real life story. In many people’s minds, the fictional heroine was the real-life Yoshiko. To make matters worse, Yoshiko also liked to promote this idea that she and her fictional self were identical, putting more distance between herself and the truth.

Since I wanted to write a biography, not a novel, I wanted to stick to the hard facts when available, and when these were impossible to find, I tried to show what was known, what was a fabrication, and what was somewhere in between. That way, readers, along with me, could try to figure what belonged to myth and what really happened.

Q: In keeping with her reputation as an eccentric, Yoshiko kept monkeys as pets. What was her fascination with them?

PB: I don’t know exactly why Yoshiko liked monkeys so much but her assistant has written that, just before the end of the Second World War, she didn’t have anything to do during the day. And since she liked animals, she bought three monkeys in Tokyo and took care of them in her hotel room. Another one was born, and so there were four monkeys all together. She really liked those monkeys! She didn’t just keep them in the house, she also went out on the town with them. One acquaintance remembers seeing her at a movie theater with a monkey on her shoulder.

After the war, when Yoshiko was in China, a judge asked her why she had returned to China where she faced certain arrest. She cited her devotion to her monkeys, saying that she had come back because one of her monkeys had developed diarrhea.

Perhaps she turned to monkeys for company because her experience with human beings had been so bad. As she herself said soon before her execution: “I don’t want to die with humans. But I’ll be happy if I die with monkeys. Monkeys are honest. Dogs too.”

Q: Lastly, rare images of Yoshiko are incorporated into your book. Which ones were your favorites?

PB: Yes, the photos are wonderful, aren’t they? I am still astonished by the photo of her with her adoptive father just after she cut off all her hair in 1925. She had really transformed herself into a male student. I had never seen that photo before I discovered it in the archive of the Asahi newspaper. The other photos of her dressed as a man are striking, so it’s hard to choose which among them is the best. A friend told me that the later photo of her dressed in a man’s suit and sitting beside her adoptive father Kawashima Naniwa is very scary, conjuring up all sorts of thoughts about their very troubled relationship.