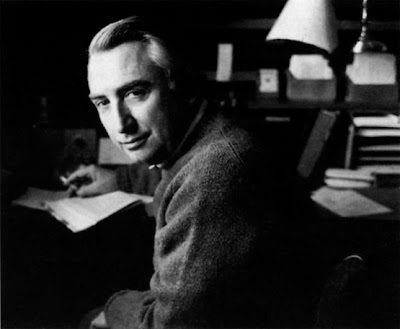

Roland Barthes on the Literary Hero — The Preparation of the Novel

“It’s this Figure—or this Power—of the literary Hero that’s dying out today”—Roland Barthes

In his lecture of February 16, 1980, Roland Barthes considers literature’s relationship to the world. In this particular excerpt he discusses the concept of literary heroism and whether it still has a place in the world. (For other excerpts from The Preparation of the Novel, click here, here, and here.)

5. Heroism

I said: disappearance of literary leaders; this is still a social idea; the leader = figure in the organization of Culture → But within the community of writers (the calling into question, not to say the decline of which I’m outlining now), another word imposes itself, less social, more mythical: hero. Baudelaire on Poe = “one of the greatest literary heroes” → It’s this Figure—or this Power—of the literary Hero that’s dying out today.

If we think of Mallarmé, of Kafka, of Flaubert, even of Proust (the Proust of In Search of Lost Time), what is “heroism”?—(1) Literature is accorded a kind of absolute exclusivity: monomania or, in psychological terms, obsession: but also, put differently, a transcendence that proffers literature as the full expression of an alternative to the world: literature is Everything, it’s the Whole of the world; radical declarations—consciously, philosophically radical—from Mallarmé: “Yes, literature exists and, if you will, alone, to the exclusion of everything”—and in the interview with Jules Huret (Revue Blanche, 1891): “Everything in the world exists to end up in a book”—and, in a less doctrinal, more existential, more heartrending manner, Kafka (letter to Felice Bauer, 1912): “should I ever have been happy outside of writing and whatever is connected with it (I don’t rightly know if I ever was)—at such times I was incapable of writing, with the result that everything had barely begun when the whole applecart tipped over, for the longing to write was uppermost.” (2) Heroism = uncompromising attachment to a Practice = the declaration of an autonomy, a solitude with respect to the world; that is to say, paradox: starting out from an Imitation (Imitation according to literature, according to the beloved Author), what’s then required is what Husserl calls a refusal to inherit (= a “dogmatism”):cf. Nietzsche (Ecce Homo, 299): “At that time, first Festival of Bayreuth, around 1876 my instinct decided inexorably against any further giving way, going along with everyone else, confounding of myself with what I was not.” (3) Third attribute of the Heroism of solitude: an apprenticeship in literature is an apprenticeship in how to be alone, to the point of it becoming a curse, which is to say, to the point of it inviting the world’s ironic disapproval. Kafka began writing around 1897–1898: one Sunday afternoon, he writes something about two brothers (one in America, the other in prison, etc.); one of his uncles reads the text out to the family, then comments: “The usual stuff” → “To be sure, I remained seated and bent as before over the now useless page of mine, but with one thrust I had in fact been banished from society, the judgment of my uncle repeated itself in me with what amounted almost to real significance and even within the feeling of belonging to a family I got an insight into the cold space of our world which I had to warm with a fire that first I had to seek out.”b. Does this kind of “Heroism” exist today? Perhaps, probably even, but we can say with certainty that literature itself (let’s prudently say what gets written) no longer bears the trace of it, no longer testifies to it. Unique and final testimony of this “Heroism”: Blanchot → But perhaps the point is that nowadays Heroism is compelled to be secret, to be unsaid; for clearly such Heroism has none of the arrogance of social (military, militant) Heroism; it’s not a particularly attractive Heroism, for it’s shot through with distress, with difficulties, to such an extent—and therein lies the desuetude—that society no longer recognizes it, that is to say, society no longer identifies it and no longer recognizes its value, its right to be acknowledged. The literature of today: brings to mind the last movement of Haydn’s Farewell: one after the other, the instruments stop playing; only two violins remain (they carry on playing the third); they remain on stage but snuff out their candles: heroic and melodic.