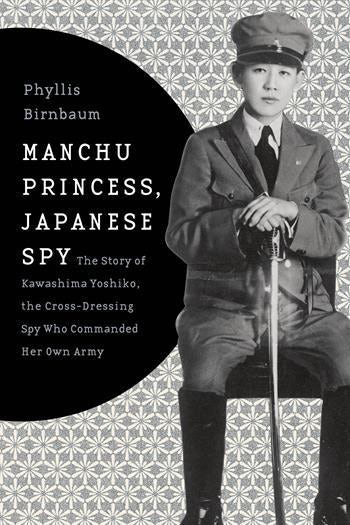

Interview with Phyllis Birnbaum, author of "Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy," Part 2

The following is part one of our interview with Phyllis Birnbaum, author of Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy: The Story of Kawashima Yoshiko, the Cross-Dressing Spy Who Commanded Her Own Army:

Q: Why begin with Yoshiko’s execution?

Phyllis Birnbaum: I didn’t want to tell Yoshiko’s story chronologically, that is, I didn’t want to write she was born, she went to school, she grew up, she died etc. I wanted to be able to jump back and forth in time, and also wanted to digress to other side issues–about what was happening in Manchuria at the time; about Emperor Puyi; about Saga Hiro, the Japanese woman married to Puyi’s brother. So telling readers about Yoshiko’s death at the very beginning is a kind of announcement that the biography is not going to be told in a “this happened, then this happened” style.

Also, as a beginning to a book, her execution is dramatic and, hopefully, catches the reader’s attention!

Q: What was Yoshiko’s attitude towards her own fame?

PB: Yoshiko had a fiery personality and loved the limelight. Actually, she seemed to take her life force from publicity and in her heyday adored giving interviews to regale her public with stories about herself—some true, some semi-true, and others completely false. She would talk about her fearless deeds as a military commander, how she kept in shape by boxing, how she had parachuted down in the freezing cold to try to get a Manchu warlord to surrender to the Japanese, how she had singlehandedly rescued an empress by stuffing her in the car trunk. She loved these stories, but after the war, when she was arrested for treason by the Chinese, she had to disavow them all, saying that they were all exaggerations and that she had done nothing to harm China. By then it was too late for the Chinese believed her old tales. So you can say that a passion for publicity proved fatal to Yoshiko.

Q: How does Kawashima Yoshiko’s story fit with the Second Sino-Japanese War and the history of Manchuria and Japan?

PB: Kawashima Yoshiko was not a central influence in the Second Sino-Japanese War—she didn’t make policy or become a high official in the puppet state the Japanese set up in Manchuria. But her escapades constantly brought her in contact with major figures—she became involved in the Shanghai Incident because of her affair with a high-ranking officer in the Japanese army and, as a fellow royal, she was charged with whisking “Last Emperor” Puyi’s wife off to that new Japanese state in Manchuria. And so her life story, with all its fascinating, dramatic aspects, is a good way to learn about that whole period.

It must be remembered that the Japanese liked to boast about Yoshiko’s cooperation with their ambitions in China for she was, after all, of the Manchu nobility and her support allowed them to brag that they were not mere ravaging China for their own sake, but rather, with a Manchu princess’ approval, they were bringing light and freedom to Manchuria, and to all of China.

This worked for a little while, until Yoshiko understood the extent of the Japanese savagery in China. Then she began to criticize them in public, and Japanese officials regretted that they had made her into such a celebrity. That’s when they began their unsuccessful attempts to assassinate her.

Q: How did Yoshiko defy traditional gender roles of 1930s and 40s Japanese society? Was there a historical precedent for this?

PB: In 1925, after series of sad episodes in her life, Yoshiko had her hair cut off into a male style and declared that from then on she would live as a man. She was about eighteen years old. From then on she often appeared in public in male attire and spoke in a style of Japanese reserved for men.” I was born with what the doctors call a tendency toward the third sex,” she wrote at the time of her haircut, “and so I cannot pursue an ordinary woman’s goals in life. People criticize me and say that I am perverted, and maybe they’re right. I just can’t behave like an ordinary feminine woman.” Here Yoshiko seems to express a wish to actually be a boy, a man, male. Read today, the statement would be considered a sincere expression of the discomfort she felt living as a woman, to be taken very seriously.

But Yoshiko found herself in Japan in 1925 and could not hope to make the kind of biological and legal changes that are now possible. So, from then on, she would startle the Japanese with such statements about her maleness, and then quickly retreat, not wishing to go too far. Yoshiko’s actions continued to be marked by such contradictions and distress. Sometimes she flaunted her love affairs with men, and at other times, dressed in severe male attire, she introduced a female member of her household as her wife. But whatever she did, she took care to keep her behavior within a range that was then socially and politically permissible in Japan.

For the most part, Yoshiko’s Japanese biographers have not attached great significance to her proclamation about becoming a man. After all, she was a flamboyant character, not given to shying away from provocative acts, and the biographers view her fondness for men’s clothing and language as just another performance. They point to the fact that the Japanese were already familiar with women dressing as men, having been exposed to so-called “modern girls,” who cut their hair short and wore Western-style clothing to demonstrate their liberation from ancient rules about female behavior. Then there was the all-female troupe Takarazuka, with certain actresses specializing in men’s roles and thrilling their many fans.

Still, it appears clear that there was more to Yoshiko’s assumption of a male identity than just a desire to playact or be the center of attention. Her public remarks can be seen as her wish to tell of something deep within her, a need to show what was real. She had endured a miserable childhood, cut off from her family in China, and was left alone much of the time or in the company of her adoptive father and his male disciples. Since her early years, she had made certain choices plain: she had shown a strong tomboyish nature and an inclination to use male language. She used this masculine-style Japanese regularly and often appear in public in her male clothing, which for those times was an extraordinary decision.