Families for Our Ideas: Beatrice Marovich in Conversation with Krista Dragomer on the Art of Sister Death

When I submitted the final manuscript of Sister Death: Political Theologies for Living and Dying to Columbia University Press, the document did not include images. Somehow, partly through the organic growth of the book and partly through happy accident, the artwork of my friend and collaborator Krista Dragomer came to be an integral part of the project itself. The works of art in the book were not created for this book. But Krista and I spent several days together, in her studio in Red Hook, thinking about pieces of hers that were in productive conversation with my work. The connections between the image and the text are neither fully intentional nor inadvertent, in other words, but something else entirely.

The two of us have been friends and collaborators for more than fifteen years. So, as I discuss in the book itself, there are many ways in which our work speaks to one another. But I wanted to illuminate some of the points of connection, and resonances, between my text and Krista’s images for readers. Below, I pose several questions to Krista about the relationship between text and image, her work and my work, and the two of us as friends and collaborators. Her responses have given me an even deeper appreciation of the way that our work is co-created. As a writer, my name is the one that’s attached to the words I choose for the page. But writing and thinking never happen in isolation. Our ideas, as Krista puts it, have families. I love this way of putting it. Schools of thought seem so structured and bureaucratic to me. Families for thinking seem appropriately messy and intimate.

Beatrice Marovich: Typically, my work doesn’t appear alongside images. And your work doesn’t typically appear alongside text. But there, in the book, text and image are in conversation. How do you think that the text changes, or speaks to, your images? And how do you think that the images change, or speak to, the text?

Krista Dragomer: I think that it’s natural for readers/viewers to want the text to explain the image, or the image to explain the text. That is not what is happening here. As you describe, in your preface, the text and the images are bodies of work in parallel, each created via our own methods and modes of inquiry, which intersected at various points over the years through our shared interests and curiosities.

What having them together in this book activates is an attentiveness to the specific material presence of each. Words have a material presence. Language was born out of a human response to our physical world. Something I love about your writing is the way in which you invoke those physicalities, those rushing rivers and roaring lions that are in the origins of the words you choose. They create these multivalent worlds and states of being that the reader can really feel. The images, likewise, have a material presence, even in a black and white reproduction. The choice to make a certain kind of mark, evoke a texture, or scale relationship, stirs up the knowledge of the physical world that each of our bodies holds. When all those worlds interact with each other on the page, it can really open up exciting perceptual spaces in the imagination of the reader/viewer.

Marovich: How much, if at all, do you think that death was present in your own mind as you created this work? And, if it was there for you, what form did it take (its relation to life, the fact of finitude or mortality, etc.)?

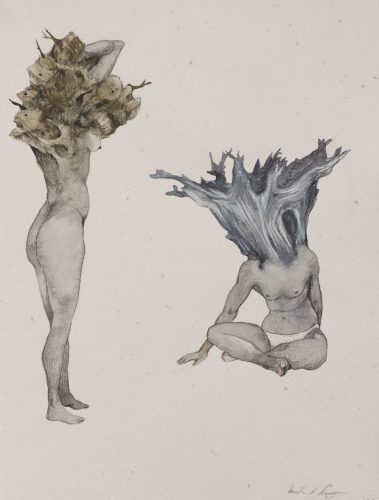

Dragomer: Many of these images were created as a meditation on indeterminate states of being. They were often created after discovering an animal carcass in the woods and feeling that power of something no longer alive but not lifeless. Or by using the mushrooms, wildflowers, and soils of a particular landscape to create the color palette. So, there was a kind of material indeterminacy in the creation of the images themselves: these organisms had been transposed from one environment to another, no longer living in their ecologies of origin, yet not not living in this new arrangement (but for how long? when does the juice of a berry become a stain, a marker of its past juiciness?).

I made many of these images to explore where the conceptual boundaries of life and nonlife break down. And if/when they do break down, what do they evoke? Can an image feel like it has transgressed the boundaries of life or death yet still be charged with “aliveness”? And if so, what is that? What are we feeling when we feel life, death, or some kind of suspension between those states in an image that isn’t explicitly depicting those experiences?

Marovich: How do you feel about having your work in a book about death?

Dragomer: While I wasn’t specifically thinking of these works as being about death, many of them were about the limits of life, which inevitably holds death in relief. I don’t make art about conditions or experiences that I feel resolved about. So, while these works are finished as individual works, the conversation they stir in me is ongoing. Having them in this book is a way for them to continue to show me new things, to expand my thinking into new shapes. I hope they can do the same for the readers.

Marovich: Do you ever think about theological ideas when you make art? If so, what names do you give these ideas? How do you feel or encounter them?

Dragomer: So much of my art making is about forms of knowing. How do we come into relation with ideas, with meaning, with individual and collective perceptions of ourselves and our internal and external worlds? What are the unseen beings and forces we are shaped by and in conversation with? What forms of power animate or dominate us? Who, or what, gets named and what is the weight of those names? How can we un-name ourselves, redraw the shapes of our beingness, or erase the separations we’ve learned to perceive between ourselves and the other beings and forces we are a part of?

So, yes, I would say that there is a kind of theological inquiry present in my work. How I feel or encounter those ideas is a question best “answered” by being with the art. That, of course, is the big mystery of it all.

Marovich: In the book, I suggest that one of the threads that ties our work together is that we each walk a thin line between beauty and horror. A lot of your work explores and works with images of women’s bodies. How do you think that your own experience of inhabiting a woman’s body has influenced the way that you think about beauty and horror?

Dragomer: A common misread of my work is that it expresses my psychosexual oneness with the world; like, nature is sexy to me, and I’m turned on and at one with all this! And it is true that I am interested in eroticism as a force that connects me to the world, in the Audre Lorde sense of the erotic. But eroticism is not about feeling sexy. It is about powerful encounters with forces of beauty and horror. Sex is a part of this encounter. But the erotic can also be an experience of shock, confusion, disorientation, and disgust.

Inhabiting a body deemed female has meant, for me, that I constantly feel the pressure to perform my relationship to eroticism in specific ways. My body is held by a public gaze that wants to shape it in its own image of beauty and desire. In my work I have experimented with this performance, answering these expectations in ways that can elicit a range of responses along that spectrum of beauty and horror.

Marovich: I don’t have any biological sisters (or siblings!). But I often think of you as a sister because we’re so close, and I depend on you. I’m torn, though, because—as I argue in the book—sisterhood can sometimes be challenging, provocative, even antagonistic. What do you think about my comments on sisterhood in the book? Do you think that our friendship is sisterly?

Dragomer: I don’t have any biological sisters either! There’s an intimacy to sharing and shaping ideas together that doesn’t have a name, but it can be powerful and challenging in all the ways that you describe. Our work in your book is definitely bound in a sisterhood. We have each been dependent upon one another’s knowledge, perspectives, interpretations, and motivations at different times in our process. I believe that work needs a family; ideas need families. The Ancient Greek usage of the word idea suggests a set of concepts with observable shared traits. I think that, in this way, our ideas are sisters. And our friendship has brought forth this sisterhood; we’ve co-created ideas that live together in family, and that family lives in us.