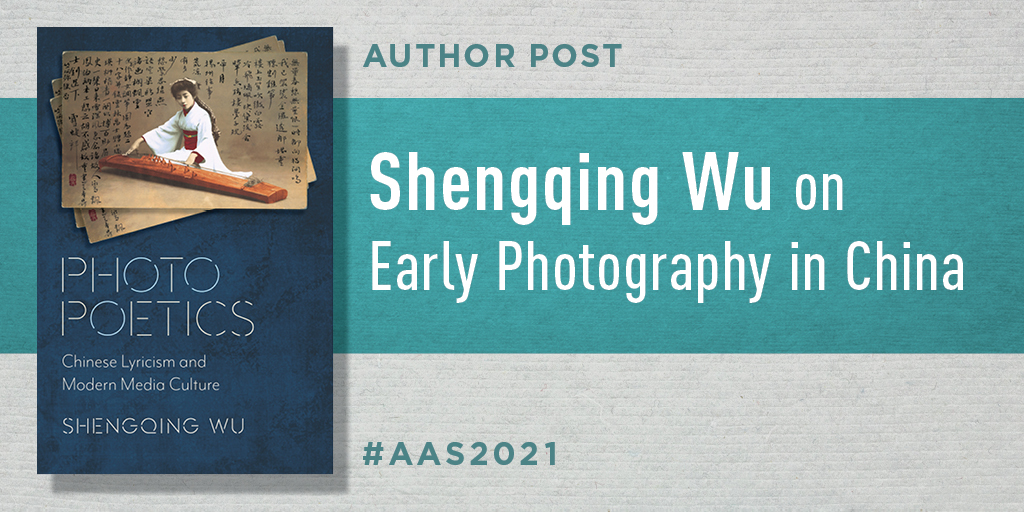

Early Photography in China

By Shengqing Wu

Chinese poetry, painting, and calligraphy have a long history of interaction and harmonious integration. But in the nineteenth century, photography was introduced into China: what happened when the brush encountered the shutter? In Photo Poetics, I explore the dynamics of transplanting photography into China, addressing how Chinese pictorial and writing traditions accommodated and responded to this new technical medium and how traditional combinations of painting, calligraphy, and poetry were extended into modern media environments. Focusing on the period from the end of the nineteenth century through the Republican era, the book examines a wide range of genres and practices concerning the collaboration between traditional forms (poetry, painting, and calligraphy) and the new visual media.

Photo Poetics illuminates the various ways photography (sheying), conceptualized as capturing shadow or illusion, was practiced in China’s flourishing urban culture and social life and the appropriation of new visual technology through Chinese ways of seeing and aesthetic concepts. By detailing how traditional ideas and forms were integrated, negotiated, or set in conflict with modern visual culture, the book demonstrates that these interwoven photos-texts, mediating a range of modern emotions (self-consciousness, gendered feelings, empathy, aesthetic friendship, etc.), encapsulate innovations and complexities in the formation of Chinese literary and visual modernities.

The following photos provide a few examples of this interplay between traditional poetic and artistic forms and the new photographic technology.

This early example of a surviving photograph from the Imperial Palace in Beijing intriguingly demonstrates how photography was couched in China’s pictorial practices. The photograph of Yi Xuan (Prince Chun, 1840–1891) and his two guards in the Imperial Palace was mounted onto a brocade as a hanging scroll. This scroll of the photograph, together with his poem, signature, and two seals inscribed on the top, is a wonderful articulation of multimediality and a welcoming gesture of accommodating photography within the Chinese painting tradition.

Photography was used to create and fashion different representations of the multiple and idealized self. Costume photos and doubled or multiplied images of the self (often with different positions, gestures, or clothing) proved to be very popular. In this circular-shaped photographic image reprinted in a courtesan photo album, a well-dressed courtesan named Fan Caixia sits around a table in three different positions. This type of doubled or multiplied figure in portrait photography, created through double exposure or combination printing, was commonly referred to as fenshen (lit., dividing bodies) or huashen (lit., transformation bodies), terms that come from Daoism and Buddhism.

Yuan Shikai (1859–1916), before assuming the presidency of the Republic of China, donned fisherman’s garb and posed as a reclusive angler (a favorite literati persona) in a series of photographs taken in the garden of his residence in Anyang. He also composed poems on this occasion, articulating his ambivalent feelings about his political ambitions. Reenactment of well-known theatrical scenes or playing at various cultural personas, including men cross-dressing as fashionable Western ladies, entertained and captured the imaginations of many.

Qiu Jin (1875–1907), a revolutionary martyr and feminist writer, enjoyed dressing in male clothing to pose for the camera. Her well-known poem “Inscribed on my portrait in male attire” documents her psychologically rich experience of viewing a cross-dressed self-image. A number of female poets (such as Xu Yunhua and Zhang Mojun) actively participated in new media culture, presenting self-portraits, accompanied by their distinct poetic voices, to the public gaze.

This is a photomontage of two nude photographs by Huang Bore (1901–1968) and four photographs of geese on the river by Wang Laosheng (1908–1961), decorated with modern musical scores. Each photograph is accompanied by a citation of a poetic couplet. This collage of modern nudity, scenery, and words is titled By the Ripple (Zaishi zhi mei), predicated upon lyrical moods and gendered fantasies as ancient as those in the Book of Songs. The development of image-printing technology and mass-produced pictorial magazines (e.g., Liangyou) further facilitated, deepened, and multiplied image-text and intermedial relationships.

Since the 1920s, pictorial photographers have endeavored to transform the technical medium into an art form for the expression of feelings and lyrical ideas. Well-known for his “composite photography,” Lang Jingshan (aka Long Chin-san, 1892–1995) composed photographic landscapes based on theories of Chinese landscape painting through combination printing techniques and darkroom manipulations. This magnificent example of his late work A Panoramic Embrace of Landscape (Hushan lansheng) is composed of ten negatives shot throughout his life, evoking aesthetic ideals of traditional handscroll paintings of mountain and rivers.

Inscriptions were persistently practiced in Republican photography. In the book, I explore a set of works by Luo Bonian (1911–2002), who collaborated with a group of well-established cultural and political figures in 1930s Shanghai. Three gelatin prints inscribed by the eminent writer Yu Dafu (1896–1945) in 1935 have survived in Luo’s archive. These collaborations have not only richly informed us of the social networking and emotional life of the time but also, in some way, foreshadowed the enthusiasm for avid photo sharing and circulation through social media in the contemporary era.

The image-text relationship is more complex, contradictory, and open-ended in contemporary artistic practices and the current digital media environment. The Shanghai artist Ma Liang created the nine photographs of Secondhand Tang Poems (Ershou Tangshi) in 2007. The canonical poem “River Snow,” handwritten in an amateur style, exists in dynamic tension with the artificially staged landscapes, skull, and fisherman figurine. Ma Liang emphatically asserts: “Photography is my magic brush.”

Shengqing Wu is professor of Chinese literature at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. She is the author of Photo Poetics: Chinese Lyricism and Modern Media Culture. You can save 20 percent on her book and any other AAS featured title when you use coupon code AAS at checkout through May 1, 2021.