Behind the Scenes of the Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry Online

“Granger’s is a portal that invites our own voyages of discovery.”

~ Tessa Kale

In continuing with this week’s “Behind the Scenes” theme, today we bring you a guest post from Tessa Kale, Senior Editor of The Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry Online.

• • • • • •

ONCE UPON A TIME Granger’s existed only as a print index of titles and first lines of poems. A librarian could reach for it when an undergraduate walked up to his desk and asked, “So what’s that poem, that begins—‘I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness’”? This was before the days of smartphones. He could answer that question (“Howl,” by Allen Ginsberg) just as quickly as when his next patron, perhaps a senior, asked—“That poem I memorized as a child, it begins, ‘I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky, And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by’—what is that?” (“Sea Fever,” by John Masefield) all thanks to The Columbia Granger’s Index to Poems in Anthologies.

I first started working on the Granger’s index as a freelance proofreader while I was a graduate student. Although I was completing an MFA, I spent much of my time in the English department taking classes in Shakespeare, and 18th and 19th century poetry, and I was auditing Kenneth Koch’s undergraduate class in contemporary poetry; so getting paid to mull over the first lines of poems was about as pleasant a way to earn a few dollars as I could imagine. In those days Columbia University Press was located in an apartment building across from the University, and I was shown to a small back room where I was to scour the very tiny printing of the index with sundry others. It was all part of the reference department, birthplace of the legendary Columbia Encyclopedia. Space was limited and at one point I sat on a stepladder with my sheaf of paper. Passionate controversy would occasionally break out: if the Granger’s style was to use sentence-style capitalization, what should you do when you had a poet like ee cummings, whose lower case was a matter of poetic conviction?

Somehow or other, within months I found myself working full time in this idyll. This was in the late 90s; the internet had come into existence, and there was a general sense that this was probably important, though no one knew how yet. The main thing was that it was probably best to “go digital.” Granger’s first went digital on a CD-ROM; here for the first time, the idea surfaced that instead of just an index, Granger’s could provide the full text of some of the poems, and commentary on these poems too, as well biographies of the poets. Before long—thanks to our canny head of reference, James Raimes—it became clear that the way forward was an online site of the index that would include poems in full text, with commentaries and biographies, audio of poets reading some of the best-known poems, as well as e-books of poetry criticism.

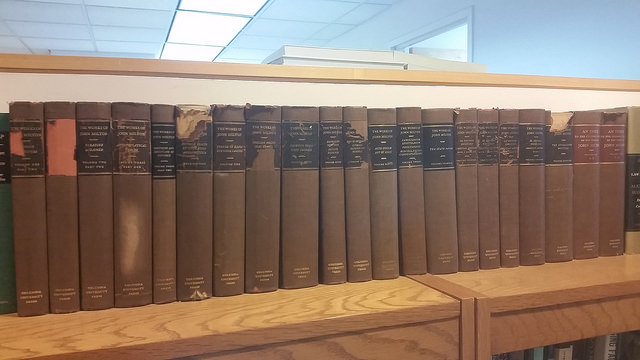

The next years were heady as we added tens of thousands of poems and came to see the many exciting ways that digital technology could be put to use for poetry lovers. We added entire texts of such long poems as Paradise Lost, and as we added Dante’s Divine Comedy we realized we should have the original languages of the great poems as well. This brought about one of our most inspired components, the “Compare Poem” feature, that allows you to read separate texts side-by-side, whether it’s original language and translation, or any two poems a person might want to see side-by-side. With so many poems in one database the possibilities for poetic inquiry became endless. Curious to know how many poems contain the word “reciprocity”? Granger’s can tell you, and show you the poems. (Not many, though Marianne Moore made use of this unpoetic word, in a poem called “Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns.”) We developed another way to explore the vast universe of poems that Granger’s contains with the subject browse, which is a thing of beauty in itself. Search for poems about love and you will find that there are 18 different categories; the greatest number of poems are under “Erotic Love” though “Romantic Love” and “Unrequited Love” get their fair share, with “Divine Love” also garnering a large number. If you have more arcane interests and are looking to see if there are any poems about the War of 1812, for instance, you can search the subject directly and find that there are 66 poems; click on the category view and you will be dazzled by a constellation of related subjects—War of 1812 falls under “War” which falls under “History”; and there are other subjects that fall under War of 1812: Chief Black Hawk, for instance, and the Battle of Tippecanoe.

To paraphrase William Blake, The Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry Online offers both the world and the grain of sand. And it’s a world that expands, becoming ever more capacious. People haven’t stopped writing poetry, of course, and sometimes it’s the voice of the contemporary poet we need to hear, resonating with our own life—or to connect with that older poetry, or to some other cultural medium, like the movies. Listen to Fanny Howe write about that great classic, The Third Man:

I dropped the book, wept and went to the movies.

It is here where I can forgive someone for his crime.

Poisoning babies for profit. Harry Lime.

I can actually forgive it when he is crawling in shit.

Otherwise we will stand on the ferris wheel together forever

stuck in the fog and iron.

Today we add the poets that may be the Milton and Dante of our own times. We continue to add biographies—so many new young poets!—and commentaries. Recently we added commentaries to Blake’s great sequences Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience and I was struck by how much our commentaries enriched my own reading of this favorite poet; simple child-like poems containing so much subtle complexity! So we are back to Blake’s finding the world in a grain of sand.

This beguiling display of largeness and smallness, complexity and simplicity, is also the essence of poetry: opening up worlds within worlds, finding Whitman’s multitudes within, through the sheer wonder of words. Granger’s is a portal that invites our own voyages of discovery.