Of Modernism and Muscle Cars, Part 1 — A Post by Laura Frost

Laura Frost is the author of The Problem with Pleasure: Modernism and Its Discontents, our featured book of the week:

“Modernism constantly puts up … resistance and, even more audaciously, it asks its viewers to value, savor, and learn to love that process of interpretive struggle.”—Laura Frost

For the dwindling demographic that still buys stamps in this age of electronic communication, the U.S. Post Office issued two notable series of Forever™ stamps this past spring: Muscle Cars and Modern Art in America (1913-1931). The first shows souped-up hot rods speeding along (“Freedom, Adventure, and Burning Rubber,” painted by Tom Fritz), and the second commemorates the centennial of the Armory Show in New York City, which introduced artists such as Brancusi, Léger, Picasso, and Braque to American audiences. One has to admire the eclecticism: muscle cars and modern art, the Dodge Charger Daytona and Duchamp.

The modern art stamps are kinetic, exuberant, and playful. Each image is a riot of colliding lines and mysterious forms. Even reproduced in miniature, they are by no means “decorative” or straightforward: rather, they present us with a host of questions. What exactly are we looking at? Why did the artist present it this way? And what are we supposed to get out of it?

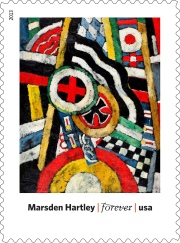

For example, one stamp in the series, Marsden Hartley’s Painting, Number 5 (1914-1915), is a colorful conglomeration of crosses, checkerboard forms, circles and lines. Is there a subject encrypted in there? The USPS notes helpfully tell us that this is “a composite portrait” of a German soldier, but it’s presented like a collage or “puzzle pieces.” And indeed, that is exactly how modernism typically presents itself: as a puzzle to be solved by the viewer.

For example, one stamp in the series, Marsden Hartley’s Painting, Number 5 (1914-1915), is a colorful conglomeration of crosses, checkerboard forms, circles and lines. Is there a subject encrypted in there? The USPS notes helpfully tell us that this is “a composite portrait” of a German soldier, but it’s presented like a collage or “puzzle pieces.” And indeed, that is exactly how modernism typically presents itself: as a puzzle to be solved by the viewer.

One of the most important principles of modernism is that it makes you, the viewer, work. Its abstraction, fragmentation, multiple perspectives, and surreal juxtapositions make you constantly aware of form—of how the artist renders the subject—often even more than the subject itself. Sure, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) purportedly depicts a naked body, but the treatment is the real interest, as a robot-like figure is shown moving across the canvas, as if by time-lapse photography with every frame displayed simultaneously. The traditional laws of time, space, and perspective are suspended.

One of the most important principles of modernism is that it makes you, the viewer, work. Its abstraction, fragmentation, multiple perspectives, and surreal juxtapositions make you constantly aware of form—of how the artist renders the subject—often even more than the subject itself. Sure, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) purportedly depicts a naked body, but the treatment is the real interest, as a robot-like figure is shown moving across the canvas, as if by time-lapse photography with every frame displayed simultaneously. The traditional laws of time, space, and perspective are suspended.

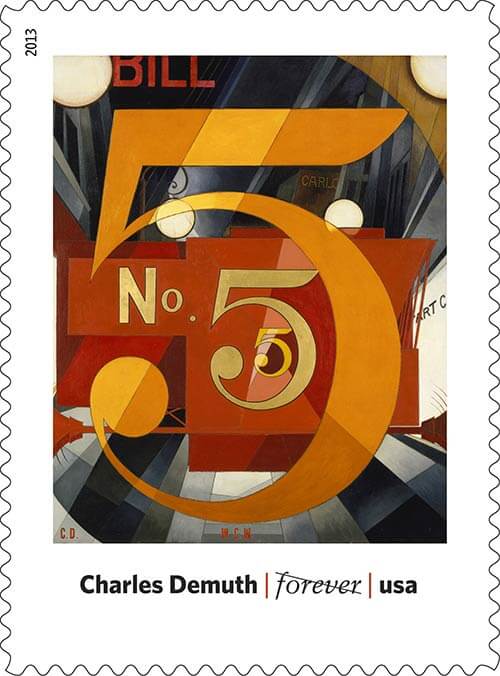

And what is going on in Charles Demuth’s painting of a massive golden number five enclosing two smaller fives over a red geometric mass and a plane of grayscale rays, with the word “BILL” drifting off the upper left part of the frame? The title, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928), is not helpful unless we get the reference to a poem by modernist poet William Carlos Williams, “The Great Figure,” an ode to a speeding fire engine. This is typical: modernism expects you to sleuth out its references, jokes, symbols, and meaning.

Putting Demuth’s I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold alongside one of Tom Fritz’s muscle cars—say, the shapely red 1970 Chevelle SS—brings the point home. Unlike a figurative painting of a landscape, a pretty woman, or a hot dragster, which you can admire for painterly technique, how faithfully the artist has captured reality, or for composition or color, modern art calls on you to analyze and interpret on a more fundamental and philosophical level. It takes a while to figure out I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold.

Demuth is more generous in his literary allusion than modernist poets such as Ezra Pound or T.S. Eliot, whose references are aggressively obscure. Unless you know many different languages and have the entire western and eastern canon of literature at your command, good luck with Pound’s Cantos or The Waste Land.

Just as modern art challenged viewers to substitute contemplation of pleasing harmonies and the artist’s mastery of technique for a more active and interpretive spectatorship, modernist writers demanded that readers decipher fragments and grapple with ambiguity. Eliot opined that “It appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult.” James Joyce commented that “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.” Modernism constantly puts up this kind of resistance and, even more audaciously, it asks its viewers to value, savor, and learn to love that process of interpretive struggle.

Tune in tomorrow for more on the story of literary modernism’s difficult pleasure and my modest proposal for a series of Modern Literature Forever™ stamps. . . .