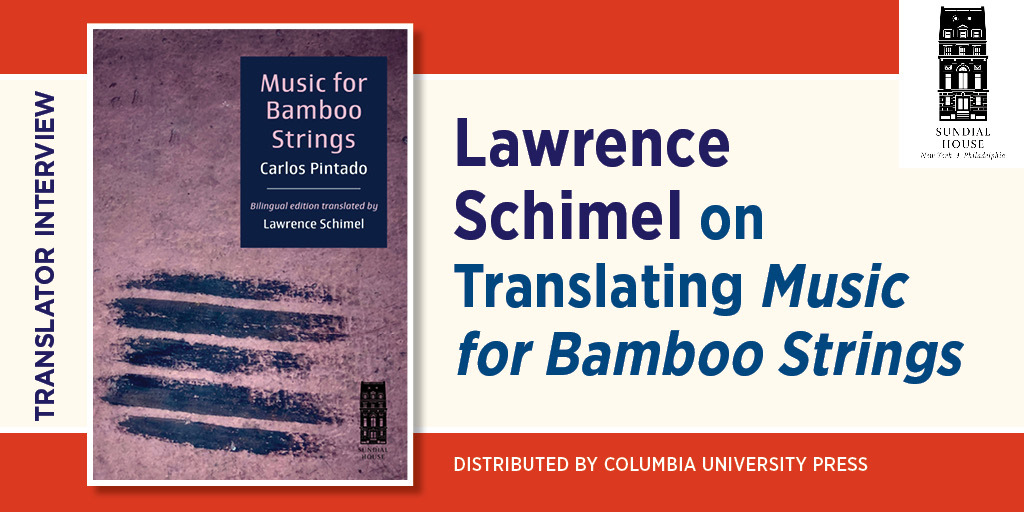

Lawrence Schimel on Translating Music for Bamboo Strings by Carlos Pintado

In “The Challenge,” Cuban-American poet Carlos Pintado writes, in English translation by Lawrence Schimel:

The distance between the rat and myself is minimal.

She looks at the house from her smallness; I look at the

house from my majesty. …

… The house, I imagine, can’t stand such

lassitude, so much unsustainable stillness. It is supposed

that between the rat and I a dialogue is established, a

war, something. But nothing happens: lesser intelligences

defying one another, we are that, in the silence.

In this entrapment, of homes, museums, books, and the objects he beholds within them, Pintado leads the reader along a path of defamiliarization, to swap the senses, and to place ourselves in the “splendor of [the] self-absorbed contemplation, the universe that contains it.” I am excited to observe Pintado “whisper[ing] over the pages for the words to resound like the unmistakable echo of the bells of a Kyoto temple,” traversing in the shadows with cameos of Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Akhmatova, and witnessing us as we “erect our love like an Ergastulum in the middle of the town square” through the meadowlark in “Moonlight in Vermont.”

“The Challenge” is one of the lyrical poems masterfully translated by Lawrence Schimel in the English edition of Pintado’s Music for Bamboo Strings. Schimel’s skills in literary translation are a tour de force in bringing this bilingual collection together. What did he consider when taking on this work? How did he bring this poem to life for the English reader? And what exactly is the role of a literary translator? Fellow translator Tiffany Troy discovers the answers to those questions and more in the following conversation.

Tiffany Troy: Can you tell us a bit about your role as a literary translator? What does literary translation mean to you?

Lawrence Schimel: I am first and foremost a reader, and one of the things I love about translating is helping other readers have access to a text they wouldn’t otherwise be able to read. And translation for me involves re-creating that reading experience in the target language, so especially for poetry, that requires evaluating all the different elements of a poem: the words and meaning and images and metaphors, syntax and tone, but also the sounds and the form, line breaks or rhyme, wordplay, so many different elements all involved in a tug-of-war to which, as translator, I strive to be true. I try to be true to the reader, to re-create that reading experience, even if that sometimes requires taking liberties in the translation.

Troy: Your definition of translation is brilliant, as is how you pay attention to re-creating the reading experience. How did you come across this project, and what was the process like in translating Music for Bamboo Strings by Carlos Pintado?

Schimel: I had translated individual poems by Carlos, years before, for literary journals, and we had met in person at various literary festivals and also when he was visiting Madrid (where I live). When he completed this new manuscript, he shared it with me and asked if I might want to try translating some work from it, to try to place in journals or submit to competitions (to publish the whole book). The translation did win the Sundial House Book Translation Award, which has led to this bilingual publication.

Before submitting the translation anywhere, I sent it to Carlos for his comments, input, and approval, and also with a few doubts or questions about certain lines and word choices. Carlos has a very high level of English, so it was a delight to get his suggestions and replies, which always helped bring the translation up a notch.

Troy: The collaborative process definitely shows in the finesse of Pintado’s poetry in translation in Music for Bamboo Strings. Turning to the prose poetry form of the collection, what are the social considerations in breaking lines where they end?

Schimel: It’s an interesting question, but also one that depends as much on the physical layout of the book, which is different than the raw manuscript I worked from. In terms of enjambments, though, very often the syntax between Spanish and English word order (noun and adjective, for instance) is the opposite, so my philosophy is usually to re-create the enjambment rather than to leave the same end word (unless there is another reason to do so, as a formal element of the poem).

Troy: In the collection, Pintado makes broad references to global mythology and historical figures, yet retains his distinct voice. How do you maintain tone across the languages, as you translate from Spanish to English?

Schimel: Trying to re-create his sophisticated, erudite tone was definitely one of the challenges for me in trying to find his voice in English! For it to sound effortless and inviting, instead of pretentious and oblique. Some of it is vocabulary and diction, some of it is syntax. But there is also a uniformity to this project that is unique to the book and different from other books by Carlos, whether poetry or prose, so a lot has to do with reading and rereading the original texts and then polishing the translations, individually but also as a whole.

Troy: Pintado is also extremely funny. How do you capture the emotional temperature of Pintado’s poetry in translation?

Schimel: This is again a question of voice when it comes to Pintado, as opposed to, for instance, another Cuban writer I’ve translated, Orlando Luis Pardo Pazo ( https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2014-09/exilium-ergo-sum/ ), whose work is filled with puns, jokes, echoes and internal rhyme, and other wordplay that didn’t always translate easily. I re-created what I could, and I sometimes compensated through using different wordplay in English but in the same place, or using the same rhetorical technique.

Troy: Can you speak about HaiCuba / HaiKuba, and specifically how the collaboration with Pintado differed from the translation process of Music for Bamboo Strings?

Schimel: HaiCuba / HaiKuba is a collaboration between Carlos and myself. We were both active participants in the creation phase, and the process was bilingual from the beginning. No matter which of us started a first draft of a haiku, in whichever language, we both were involved in shaping both the English and Spanish texts, and because they are parallel haikus we almost always tweaked the “original” in some way once we had worked on the haiku in the other language.

Music for Bamboo Strings, even though it was first published in a bilingual edition after winning the Sundial House Book Translation Prize, is a book wholly written by Carlos and wholly translated by me, although not until after the creative process was already finished.

Troy: Finally, do you have any closing thoughts for your readers of the world?

Schimel: I would say “our” readers, rather than just mine, not just because the book is bilingual but also because it is a product of both of us. And like any author (and translators are the authors of our translations), I guess all I can hope for is that readers find and respond to the work.