Will Race and Gender Influence Opposition to Kamala Harris?

Matthew Tokeshi

Kamala Harris is the first Black woman to be a major party’s nominee for president. Her candidacy raises the question of whether race and/or gender will be grounds for opposition. In my book, Campaigning While Black, I answer this question based on data I collected during the 2020 campaign, in which she ran as Joe Biden’s vice-presidential running mate.

There are reasons to think that both racism and sexism will have a large influence on how Harris is evaluated. A long line of political science research demonstrates that voters’ decisions are “group-centric,” meaning that people form their opinions on political candidates based on their attitudes toward the social groups that candidates appear to stand with or against. Perhaps the most effective way a candidate can signal their association with a social group is to actually belong to that group. As a Black woman, Harris makes both Black and female identity salient by embodying it.

My basic approach to evaluating the impact of race and gender is to conduct a thought experiment, asking: How would racial attitudes influence support for the real-life Black Harris compared to a hypothetical white clone of Harris (to assess the influence of racial attitudes)? And how would gender attitudes influence support for the real-life woman Harris compared to a hypothetical male clone (to assess the influence of gender attitudes)? This is, of course, impossible to observe, but it is possible to compare her to a similar white female politician and a similar Black male politician.

As a Black woman, Harris makes both Black and female identity salient by embodying it.

In Study 1, I compare the influence of racism on Harris evaluations to its influence on Hillary Clinton evaluations. I also compare Harris to Barack Obama when assessing the influence of gender attitudes.

If racism is an unusually strong influence on evaluations of Harris, we would expect racial resentment to be a significantly stronger predictor of Harris evaluations compared to evaluations of a comparable white woman like Clinton. And if sexism is an unusually strong influence on evaluations of Harris, we would expect gender attitudes to be a significantly stronger factor in Harris evaluations compared to evaluations of a comparable Black man like Obama.

My data came from an original survey of 3,516 white American adults conducted in October 2020 by the survey firm Lucid. I asked respondents for evaluations of Harris, Clinton, and Obama, as well as their own racial attitudes and gender attitudes, using well-established scales that political scientists use to measure those concepts. I also asked respondents about their partisanship, ideology, demographic characteristics, and other information in order to rule out other plausible influences on candidate evaluation.

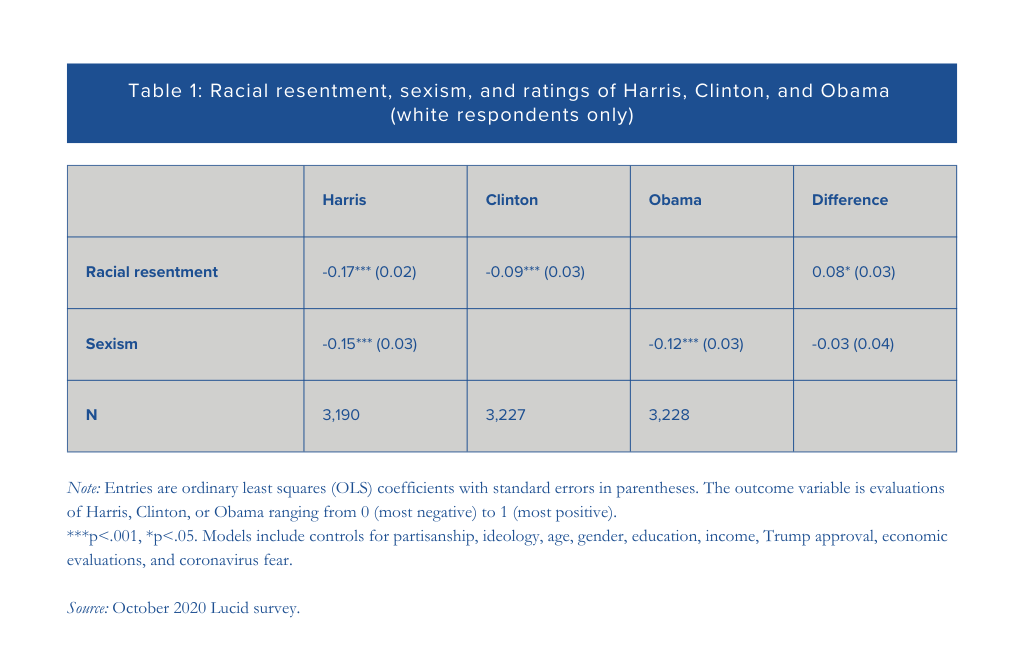

Table 1 shows the results. In the first row, holding other factors constant, moving from the least to the most racially resentful respondent decreased support for Harris by about 17 percent of the scale’s range. A similar shift decreased support for Clinton by only about 9 percent of the scale’s range. The eight-point difference is statistically significant.

In the second row, we see a slightly stronger influence of sexism on evaluation of Harris compared to Obama, but this difference is not statistically distinguishable from zero. In sum, it appears that racism had a marginally greater influence on evaluations of Harris while sexism did not.

My strategy of comparing Harris to other real-life political figures is an often-used approach among political scientists, but it suffers from the weakness that Harris and Clinton are not the same in every respect except their race, and Harris and Obama are not the same in every respect except for their gender.

For a better causal test of the effects of race and gender, I conducted Study 2, an original survey experiment in February 2021 on 1,740 white respondents, again with Lucid, that holds Harris constant and varies the salience of her race and gender.

The experiment randomly assigned respondents to one of four conditions:

- The first group read a short news article that highlighted Harris’s Black identity by describing the pride felt by Blacks in her becoming the vice president.

- The second group read an article about the pride felt by women.

- The third group read an article about the pride felt by South Asians.

- The fourth group read a nonpolitical news article similar in length and formatting to the other three.

The analytical strategy was to compare the predictive strength of 1) racial attitudes when Harris is framed as Black compared to something else (a woman, South Asian, or no framing); and 2) gender attitudes when Harris is framed as a woman compared to something else.

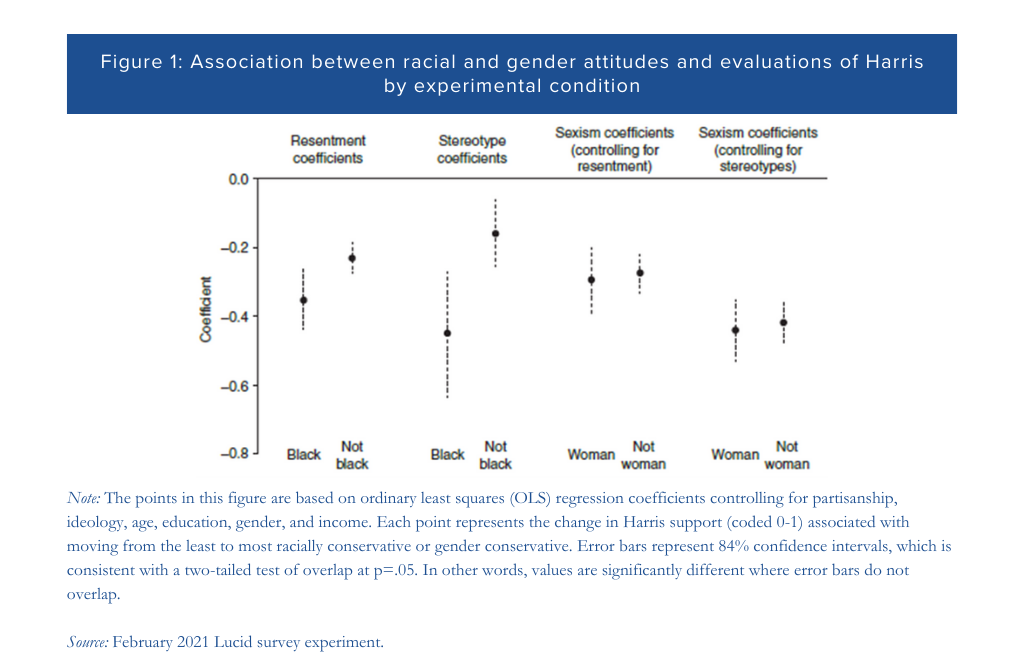

The results, shown in figure 1, are in line with the findings from Study 1. The left panel shows that racial attitudes (measured using the well-established racial resentment battery) are a stronger predictor of opposition to Harris when she is framed as Black compared to when she is framed as something else. The left center panel shows the difference in the predictive power of an alternative racial attitudes measure: belief in anti-Black stereotypes. Both differences are statistically significant.

The center-right and right panels show the difference in sexism’s predictive power when Harris is framed as a woman compared to when she is framed as something else. The center-right panel shows estimates of sexism’s influence controlling for racial resentment, while the far-right panel shows estimates controlling for belief in anti-Black stereotypes. Regardless of how racial attitudes are accounted for, sexism is a slightly stronger predictor when she is framed as a woman, but the differences are not reliably different than zero.

In sum, these results are in line with the results from Study 1, which is to say that Harris’s race appears to increase the salience of racial attitudes, but her gender does not appear to similarly raise the salience of gender attitudes.

The null finding on gender activation is not to say that sexism doesn’t matter. Previous research has shown that sexism mattered more in evaluations of Hillary Clinton in 2016 than in evaluations of any recent male Democratic presidential candidate. This is not surprising, as Clinton has long been a symbol of American feminism. And the findings described in this post may not translate to the 2024 election because Harris is pursuing the highest office in American politics, which may trigger more gender-related anxiety than her 2020 vice-presidential run. The point here is that gender may be more of a factor in some campaigns than others, depending on whether the circumstances favor it.

But in the long run, race may prove to be a more consistent mobilizer of opposition than gender. One reason is that there are clearer electoral incentives to appealing to negative racial attitudes because much less than half of the electorate in every American state is Black while about half of the electorate is women. Survey research shows that many Americans hold ambivalent attitudes about Blacks and women. But simple electoral math is one structural reason to expect race to be the more consistent factor in shaping opposition to Black women like Harris.

Matthew Tokeshi is an assistant professor of political science at Williams College, and the author of Campaigning While Black: Black Candidates, White Majorities, and the Quest for Political Office.