Lanaw Benson: An Unusual Manumission Story Sara Cedar Miller

In James Riker’s definitive history of colonial Harlem, Lanaw Benson makes her only appearance in a footnote. In discussing a four-acre property that included a sliver of the future Central Park, Riker noted that “[David] Waldron sold it, June 6, 1793, to Lanaw Benson (colored woman).”[1] Yet research reveals that Lanaw holds an important, possibly unique, place in Central Park and New York City history.

The description combining “Benson” and “colored” caught my attention. Samson Benson, grandson of a Danish-born immigrant, acquired his father’s Harlem property in 1701, and by his death in 1740 he owned so much uptown property that Riker considered the Benson name a “synonym” for Harlem.[2] Four of Benson’s nine children—Adolph, Benjamin, Catherine, and Catalina—would own land in the prepark. The Bensons also enslaved many people. Records indicate that Samson moved from Albany to Harlem “with a negro and a plow,” and the number of people enslaved by the Bensons grew from there.[3] That Lanaw was a “colored” person with the Benson surname could only mean, I surmised, that she was enslaved by a family member.

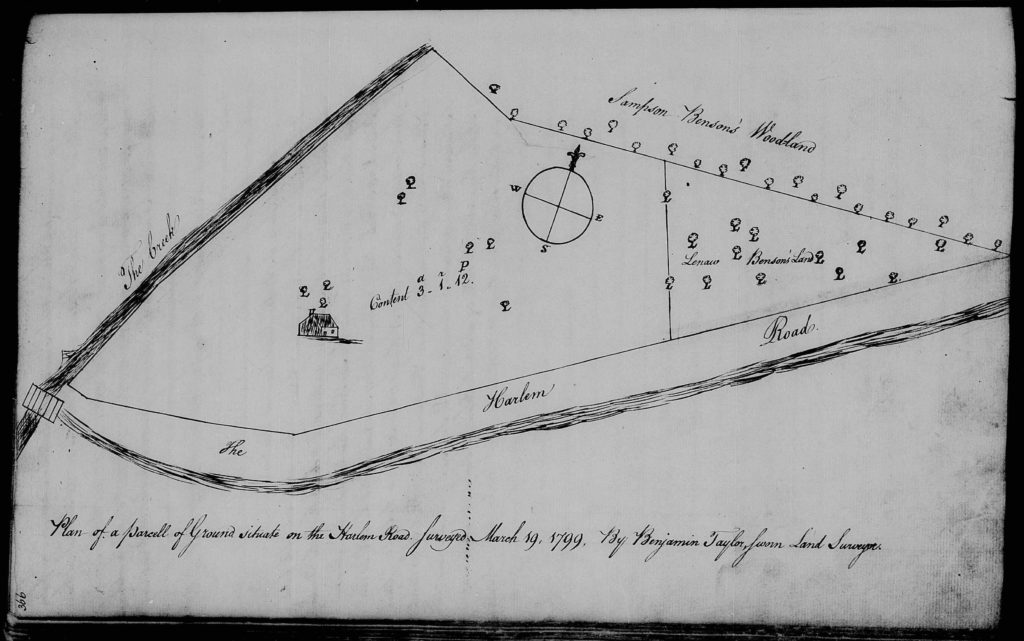

The triangular four-acre property that David Waldron sold Lanaw Benson for £18 ran along the Harlem Creek, whose western shoreline touched lightly on what is now the northeast corner of Central Park between 109th and 110th Streets, Duke Ellington Circle, and the land northeast to 113th Street and Madison Avenue. In 1799, Lanaw sold 3.25 acres of it—including the Central Park sliver—to Scottish grocer John Rankin for £221, over eleven times the price she paid to David Waldron. Benson kept the three-quarter-acre wooded tip of the wedge, lying midway between Fifth and Madison Avenues from 111th to 113th Streets, for herself. This curious sale begs the question: Why would John Rankin have spent so much money on such a tiny, remote, and unimproved plot of land?

The illustration of the divided property appeared in the 1799 conveyance in which Lanaw Benson sold most of her property to John Rankin. She transferred the house onto the three-quarter-acre tip that she kept for herself. A portion of the land became the future Central Park: where the bridge over the Creek at 109th Street on the east side of Fifth Avenue (lower left) continued one block to 110th Street.

The answer lies in a punitive New York State law from 1712 that mandated a stiff £220 payment to the state in order to manumit, or set free, an enslaved person, and an additional £20 annuity to support the freed person so he or she would not be a financial burden on the government. This exorbitant penalty stood between bondage and freedom for most enslaved people.[5] But not for Lanaw Benson.

No record has come to light of a relationship between David Waldron and John Rankin, but I propose a possible explanation for both the conveyance and the manumission. Let’s assume that David Waldron sold Lanaw her land for £18 to ensure her financial security, but could not or would not pay the required £200 to manumit her. In his book Somewhat More Independent, historian Shane White revealed new initiatives taken by enslaved people in New York to attain their freedom. If, for example, an enslaved person could not buy his or her freedom from their enslaver, they often sought out a third party to do so in exchange for years of indentured servitude.[6] Instead of this more usual arrangement, Lanaw Benson sold John Rankin the greater portion of her property as an investment, while keeping three-quarters of an acre and a house to assure her financial independence in lieu of the requisite annuity. Further explanation may never come to light, but one thing is both certain and remarkable. Not only was Lanaw Benson the first Black person to own property in the prepark, but the land that she sold to John Rankin remains the only known place in the future park—possibly in all of New York City—that was purchased in order to free an enslaved person.

Addition research revealed information on Lanaw Benson’s family and property, described in detail in Before Central Park.

Sara Cedar Miller is the historian emerita of the Central Park Conservancy, which she first joined as a photographer in 1984. She is the author of Before Central Park, available spring 2022.

[1] James Riker, Revised History of Harlem (New York, 1904), 802.

[2 Riker, Revised History of Harlem, 426.

[3] Riker, Revised History of Harlem, 429.

[4] Photocopy of Adolph Benson’s 1854 Last Will and Testament, and Tanneke Benson’s 1773 Last Will and Testament in the Notebook “The Dyckman Papers, Box 7,” Boscobel, Garrison, NY. Last Will and Testament of Adolph Benson, New York Probate Records, L44, P252, February 26, 1803; Tanneke Benson, New York Probate Records, L33, P4, June 2, 1780; Riker, Revised History of Harlem, 705.

[5] Jill Lepore, “The Tightening Vise: Slavery and Freedom in British New York,” in Slavery in New York, ed. Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2005), 81; Rhoda G. Freeman, The Free Negro in New York City in the Era Before the Civil War (New York: Garland, 1994), 8. Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery, African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 39; New York State, The Colonial Laws of New-York From the Year 1664 to the Revolution, vol. I (Albany: James B. Lyon, 1894), chapter 250, December 10, 1712, 761–762.

[6] Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City 1770-1810 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 107-111.

Related Posts

-

-

-

-

-

African American / Black Studies / American History / American Sociological Association / Author-Editor Post/Op-Ed / Black History Month / History / Human Rights / International Studies Association / Sociology

African American / Black Studies / American History / American Sociological Association / Author-Editor Post/Op-Ed / Black History Month / History / Human Rights / International Studies Association / SociologyReconceptualizing Justice for the Victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Nicole Iturriaga

-

-

-