Where Are the Women Writers? The Missing Literature of Japan’s Edo Period

By G. G. Rowley

Writing by Japanese women flourished from the late tenth through the early fourteenth centuries. Almost all of the surviving works from this period have now been translated into English, some more than once, and many are available in editions suitable for classroom use, among them The Sarashina Diary. In recent years, the reception of Japanese women’s writing over the longue durée has been the focus of sustained critical attention: Gergana Ivanova’s Unbinding The Pillow Book; Michael Emmerich’s The Tale of Genji: Translation, Canonization, and World Literature; and the anthology of translations edited by Thomas Harper and Haruo Shirane, Reading The Tale of Genji, are three notable examples. Writing by Japanese women from the modern period has also been widely translated: The Modern Murasaki is only one of more than a dozen anthologies produced for classroom use since the 1980s.

But where are the women who wrote during Japan’s early modern period? Women writers are missing from the history of the literature of the Edo period, 1603–1868—at least as that history has been told since the end of World War II. Several anthologies published over the past twenty years, including Haruo Shirane’s epoch-making 1000+ page Early Modern Japanese Literature, present a wide range of texts, most of them by men, to English-language readers. These anthologies also reveal that the established canon of Edo period literature still excludes almost all writing by women.

Still, compared to the wealth of work by men available in English, writing by women has been neglected.

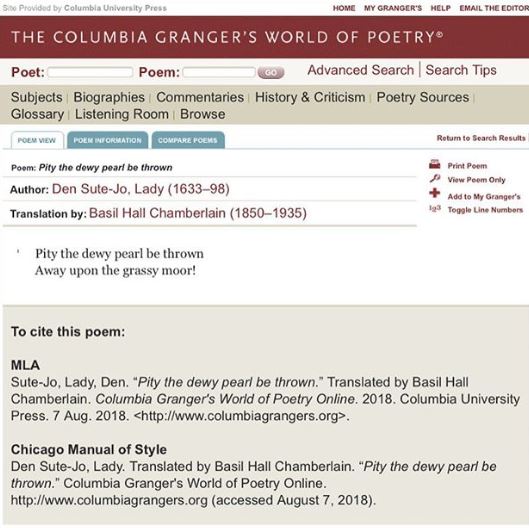

In the prewar period, Japanese scholars and writers made huge efforts to gather, transcribe, and publish writing by early modern women. In 1915, for example, Yosano Akiko (1878-1942) published a two-volume edition of the novels (shōsetsu—Akiko’s preferred term) of Arakida Rei (1732–1806), who she considered the best woman writer since Murasaki Shikibu (ca. 978-1019). So far, only one of these short novels has been published in English (“Fireflies Above the Stream,” translated by Kyoko Selden, Review of Japanese Culture and Society 20, 2008). Kate Wildman Nakai, editor of the flagship journal Monumenta Nipponica from 1997 through 2010, published several translations of writing by Edo period women, among them Record of an Autumn Wind (1771) by the haikai poet Shokyū-ni (1714–1781), translated by Hiroaki Sato; and the political treatise Solitary Thoughts (1817–1818) by Tadano Makuzu (1763–1825), translated by a group of scholars led by Bettina Gramlich-Oka.

Still, compared to the wealth of work by men available in English, writing by women has been neglected. It’s curious: thanks to the efforts of Patricia Fister, visual art created by Japanese women in the period 1600–1900 has been the subject of multiple exhibitions and catalogs, and both haiku and collections of Chinese-style poetry by women, such as Breeze Through Bamboo by Ema Saikō, have appeared in English. Waka poetry by nineteenth-century political activists also features in a biography of Matsuo Taseko by Anne Walthall and a biography of Kurosawa Tokiko by Laura Nenzi.

When we turn our attention to Japan’s neighbors, we find several enormous anthologies of Chinese literature by women. Korea, too, has been well-served by scholar-translators, most memorably JaHyun Kim Haboush, whose version of Hanjungnok (1795–1805), titled The Memoirs of Lady Hyegyŏng, so intrigued the British novelist Margaret Drabble that she wrote a novel based on it (The Red Queen, 2004).

There is nothing comparable for Japan.

There is nothing comparable for Japan. In the Shelter of the Pine is the first full-length memoir by a Japanese woman writer from the early modern period available in English.

I translated In the Shelter of the Pine for various reasons, the desire to fill a huge gap in the record only one of them. There was also the chance to reveal something of the lives of the women who made possible the success of the man at the center of the story; and the challenge of rendering Ōgimachi Machiko’s flowing, at times even a bit precious, neoclassical language, which incorporates countless allusions to earlier poetry and prose. Tuning my ear to hear Machiko’s narrative voice and transposing it into English were deeply pleasurable struggles.

Let me stress too that the appearance in 2007 of Miyakawa Yoko’s annotated edition of Machiko’s holograph meant that for the first time it was possible to translate the whole text in a reasonable length of time. One of the reasons why so few of us have ventured to translate writing by Edo period women is because their work is not canonical, and therefore unstudied by Japanese scholars. The manuscripts of writers such as Inoue Tsū (1660–1738) and Arakida Rei have been transcribed and printed, but they remain at best only lightly annotated, their densely allusive language hard to access. I hope that younger scholars will not be deterred by these difficulties—there are many more voices still to be heard.

G. G. Rowley teaches English and Japanese literature at Waseda University in Tokyo. She is the translator of In the Shelter of the Pine: A Memoir of Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu and Tokugawa Japan.