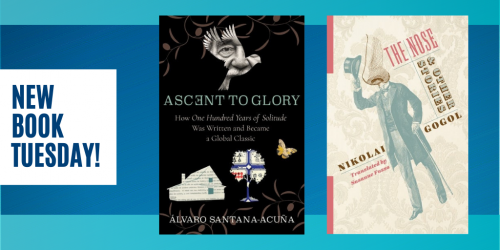

Q&A: Susanne Fusso on The Nose and Other Stories

“The first major English translation of Gogol’s stories in more than twenty years, The Nose and Other Stories captures his humor and complexity brilliantly. This volume will prove to be a great read for students and Russian literature enthusiasts alike.”

~Bruce Holl, Trinity University

We are continuing our Translation Month celebration today with a look at Nikolai Gogol’s The Nose and Other Stories, a new addition to our Russian Library series. Written between 1831 and 1842, these stories span the colorful setting of rural Ukraine to the unforgiving urban landscape of St. Petersburg to the ancient labyrinth of Rome. Translator Susanne Fusso introduces Gogol and his work and provides an inside view of what she considered when translating this collection.

Enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book!

• • • • • •

Q: Who was Gogol? Why is he important?

Susanne Fusso: Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852) was one of the most popular and acclaimed writers of the nineteenth century in Russia, and his works continue to be central classics of the Russian literary tradition. He exerted a powerful influence on writers like Dostoevsky, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Vladimir Nabokov, who called him “the strangest prose-poet Russia ever produced.” Gogol was born in what is now central Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) to a landowning family and grew up speaking both Ukrainian and Russian and reading both Ukrainian and Russian literature. He moved to St. Petersburg as a young man and also spent years in Western Europe, mainly in Rome. His bilingualism and biculturalism are an integral part of what makes his art distinctive, both linguistically and imaginatively. Although all his published works are in Russian, they are imbued with Ukrainian culture and language. This sets him apart among the major writers of the nineteenth century, who are more wholly embedded in Russian culture and particularly the culture of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Gogol brought a vivid, outsider’s eye to Russian reality. In “The Nose,” we see St. Petersburg through the eyes of a man whose nose has left his face. As Major Kovalyov chases his vagabond nose through the city, familiar landmarks like Kazan Cathedral take on a new, nightmarishly hilarious aspect. This recasting of familiar reality in an absurd light is characteristic of Gogol’s artistic practice.

What is the significance of his stories within his overall life’s work?

SF: Gogol made his first impact as a short-story writer, with the collection Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, and he continued to publish stories throughout the most productive part of his career, from 1831 to 1842, even as he became a celebrated playwright (The Government Inspector) and novelist (his masterwork, Dead Souls). His stories display all the sparkling facets of his genius: his absurd humor, his drive to confront demonic evil in everyday life, and his probing into questions of national identity.

What is the rationale for the selection of stories in this volume?

SF: This edition includes one story from each of Gogol’s first two collections, which were set in Ukraine and brought a vivid sense of exoticism and local color to the Russian audience. But my selection is centered on the stories Gogol wrote during the mature phase of his career, stories that are set in St. Petersburg, the Russian provinces, and Rome. An unusual feature of this collection is the inclusion of the original 1835 version of “The Portrait” rather than the revised version published in 1842, which seems to have been intended to satisfy a critic’s dissatisfaction with the story’s supernatural elements. The original version belonged organically to Gogol’s most Romantic work, the collection Arabesques, where it appeared alongside “Nevsky Avenue” and “Diary of a Madman.” Reading the 1835 version of the story helps us understand Gogol’s evolution from his earlier stories, in which witches and devils openly interact with mortals, to his later style, in which the supernatural and the demonic are encoded into a seemingly realistic milieu. This volume, unlike most English-language collections of Gogol’s stories, also includes “Rome (A Fragment).” This narrative of a young Italian nobleman’s passionate engagement with the cities of Paris and Rome reveals Gogol, at the height of his powers, reaching for a new mode of literary exploration, trying to capture in words the visual splendor of Rome’s art and nature. He also strives to achieve an understanding of national identity and national difference on a large scale, something he was grappling with simultaneously as he wrote Dead Souls.

What are the exciting parts of the translation process for you?

SF: My first encounter with Russian literature was reading a collection of Gogol’s stories translated by David Magarshack when I was twelve or thirteen years old. I was instantly captivated and went on to devour the works of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Turgenev. I grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, where Russian literature was not a daily topic of conversation, so I am eternally grateful to dedicated translators like Magarshack, Constance Garnett, and Andrew R. MacAndrew, who opened up the world of Russian literature to me before I learned to read it in the original. I have translated works by Vladimir Sergeevich Trubetskoi and Sergey Gandlevsky, but in those cases I was the first to translate the originals into English. This was a very different experience, as I felt the weight of adding something new to works that had been translated many times. Gogol has been a part of my life for decades—I wrote my dissertation on Dead Souls, which evolved into a book, and I have taught his stories every year of my career at Wesleyan University. Doing this translation felt like entering into an even more intimate relationship with a writer I thought I knew thoroughly.

The most intriguing and exciting part of translating Gogol is trying to capture the essence of his humor. It is not an openly jokey humor—it is usually signaled by a subtle shift in our usual expectations, as when key plot elements in “Diary of a Madman” are conveyed both to the hero and to the reader via letters written by a little lapdog. It is not so much the idea of a dog writing letters, or the particular style of the letters (the lapdog’s tone of a snobbish denizen of high society filtered through her dog’s-eye view, centered on tastes, smells, and other dogs), or the fact that both the madman hero and the supposedly sane reader accept the information given in the letters as fact—it is the combination of all these elements that makes the humor distinctively Gogolian. There are countless examples throughout these stories of this kind of celestial confluence of absurd elements. At the same time that he makes us laugh, Gogol makes us confront existential questions of good and evil—along with a young man attacked by demons in a desolate church at midnight or a middle-aged man whose overcoat is stolen as he returns from a party across a dark and deserted city square. It is this combination of profound humor and profound sadness—what Gogol himself called “laughter perceptible to the world and tears that are unperceived by and unknown to it”—that enchanted me at age thirteen and continues to enchant me to this day.

We encourage our readers to support independent bookstores. Bookshop.org makes it easy to order from bookstores across the nation and this map can help you find a bookstore near you. Visit LitHub for a curated list of black-owned bookstores.