Quan Manh Ha on Other Moons

“Unlike much of the large body of fiction from American writers that deals with what the Vietnamese call the “American War,” these stories, most of which are set in rural areas of the country and feature humble characters, focus less on the experience of combat and more on its lingering effects in the national life. . . . Readers seeking a broader perspective on Vietnam will find much of interest here.”

~Kirkus Reviews

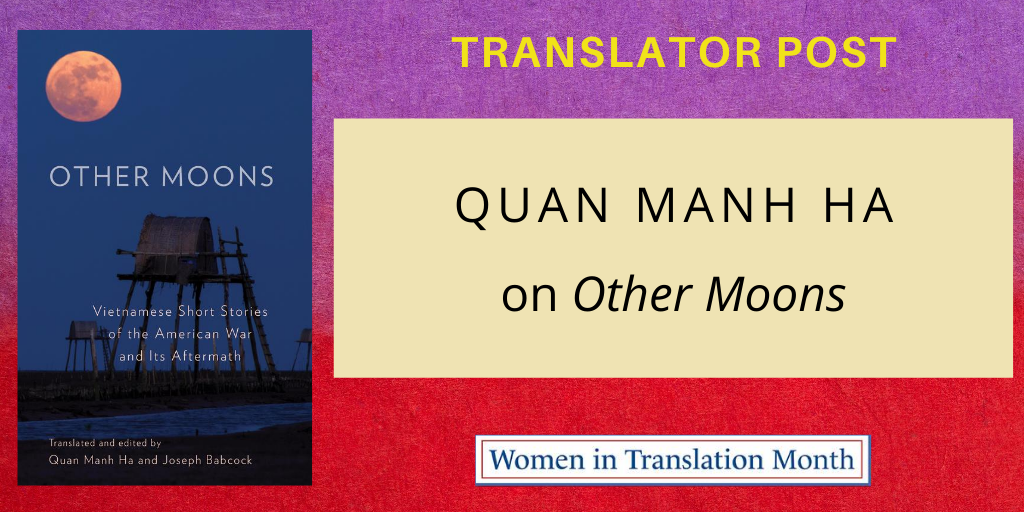

It’s the third week of Women in Translation Month, and this week, we’re traveling to Southeast Asia and shifting our focus to an anthology of fictional works that describe what the Vietnamese term the American War. In today’s piece, Quan Manh Ha, who cotranslated and coedited Other Moons: Vietnamese Short Stories of the American War and Its Aftermath, introduces us to its women writers and their stories. Read on to learn more, and remember to enter this month’s drawing for a chance to win a copy of the book!

• • • • • •

Not much literature by Vietnamese women writers has been translated into English. Most recently, Other Moons: Vietnamese Stories About the American War and Its Aftermath includes five stories by contemporary Vietnamese women writers—most notably Nguyen Ngoc Tu, Nguyen Thi Thu Tran, Nguyen Thi Am, Nguyen Thi Mai Phuong, and Vo Thi Hao. Their stories focus on the female experience in wartime Vietnam and how women reexamine the long-lasting impacts of the war upon Vietnamese society and culture.

Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s “Birds in Formation” portrays the domestic tension between two cousins, sons of two brothers who fought on two opposite sides of the war. The older brother adopted his dead younger brother’s son after the war ended. The grandmother in the story, although she was not involved in the fighting, is constantly tormented by the unfounded assumption that her older son shot her younger son during the war and blames the her older son for his crime, “You shot and killed my son Ut Hon.” It is said that in war, when a bullet is fired, it goes through the heart of the mother first. This story demonstrates this idea poignantly yet beautifully. The grandmother’s sobbing and accusation ignite the narrator’s cousin’s skepticism about his uncle and distance toward the members of his adoptive family. (Read on excerpt of “Birds in Formation”).

“The war deprives the women of their lives, their happiness, and romantic love while changing them into grotesque and ghostly individuals.”

Vo Thi Hao’s “Out of the Laughing Woods” features five women who are in charge of an army supply depot located “deep in the ghostly arms of the forest.” The chemicals that the Americans spray on the Vietnamese landscape contaminate the river where four of them bathe, and as a consequence they become miserably bald while fine hair is a symbol of female beauty. Living in isolation in the forest for many years, they develop a “laughing disorder,” a kind of hysteria, that is associated with the “wild, cruel laughter of war.” During an attack, only Thao survives, and her postwar life is haunted by the tragic death of her four comrade sisters as well as by their frenzied laughter echoing in her sleep. The war deprives the women of their lives, their happiness, and romantic love while changing them into grotesque and ghostly individuals.

War literature is often written by men and about men. These stories enrich the corpus by portraying the victimized women on the battlefield and at home and giving their perspectives on the cruelties of war.

“Contrary to the Hollywood depiction of Vietnam as a place of war, this collection paints a vivid picture of a country rich in culture, traditions, natural beauty, and history, where the past is intertwined with the present.”

As for nonfiction, Last Night I Dreamed of Peace, a diary by a communist medic, Dang Thuy Tram, was first published posthumously in Vietnam and became a best-seller there in 2005; its English translation was released in the United States in 2008. The diary enables U.S. readers to reconsider the war and adjust the dehumanized image of the Vietnamese communists projected by most American writers. The diary also questions the “just cause” label for the Vietnam War, which the United States has claimed.

Another Vietnamese writer you should read is Nguyen Phan Quế Mai, whose acclaimed novel, The Mountains Sing, is a New York Times Editors’ Choice in 2020. Quế Mai translated her poetry into English, together with the Vietnam veteran and poet Bruce Weigl. Their book of translations, The Secret of Hoa Sen, features fifty-two poems written by Quế Mai over the course of her literary career and leads the reader into contemporary Vietnam. Contrary to the Hollywood depiction of Vietnam as a place of war, this collection paints a vivid picture of a country rich in culture, traditions, natural beauty, and history, where the past is intertwined with the present. Unlike other poets of Vietnam, Quế Mai pays homage to disadvantaged groups, whether they are garbage collectors, street vendors, or manual laborers.